Nestled peacefully along the marshy south shore of Lake Jesup, Winter Springs is regularly listed as one of the best places to live in Florida. Its beautiful, well-manicured streets have limited commercialization; its town leaders have made it a point to shun big box stores.

Today it is a suburban town of 35,000 with the feeling of just now hitting its stride. Perhaps that’s because it got off to a slow start. During the 1800s, development was hampered by legally-tricky Spanish private land grants. The lack of major railroads and highways then continued to slow its pre-1950 advancement relative to its neighbors.

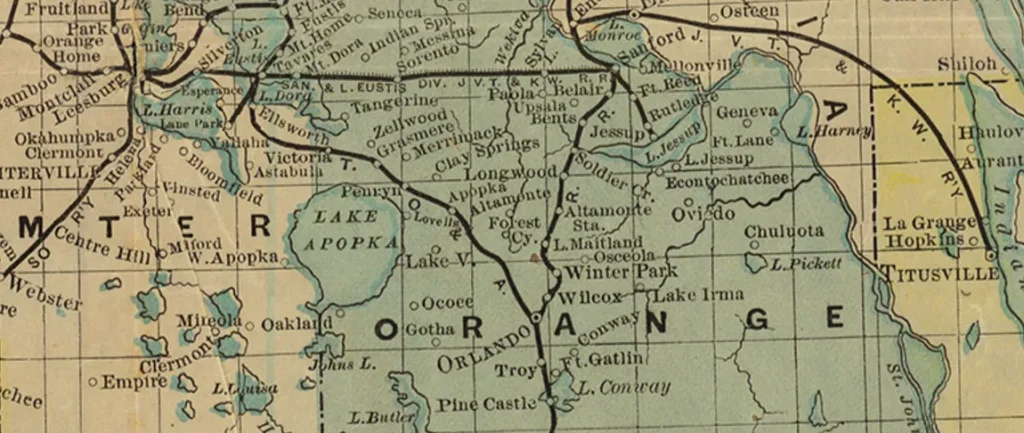

Before being incorporated as North Orlando in 1959, the area was variably known as Wagner, Clifton, Tuskawilla, Alluvia, Gee Hammock, Econtohatchee, White’s Landing, Solary’s Wharf, and Lake Jesup. It served as the southernmost terminus for steamboats from the St. Johns River before railroads became the dominant form of transport after 1880.

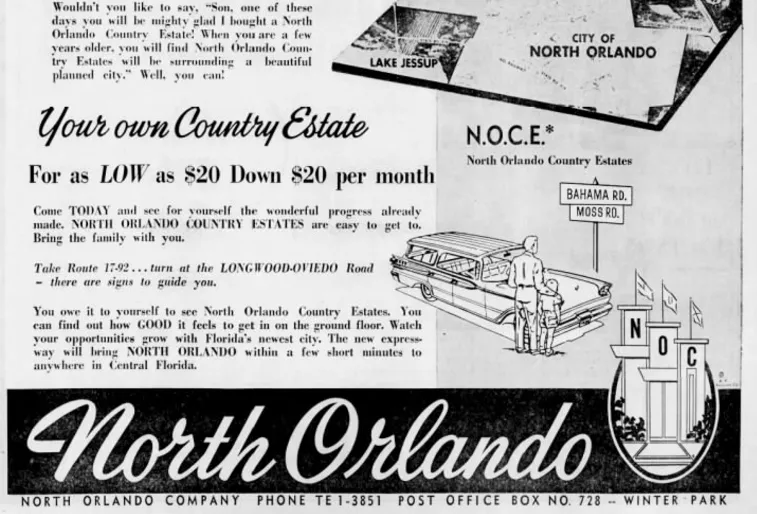

The modern town’s “founding fathers” (if you can call them that) were Ray Moss and William Edgemon, whose names locals recognize from prominent street names in “downtown” Winter Springs today. However, the duo never lived in the city at all. They were simply principals of the North Orlando Company, who kick-started the development of the western end of town in the late fifties and early sixties.

Almost immediately, residents became dissatisfied with the name “North Orlando.” Despite what the name might indicate, the village did not adjoin the northern end of the City Beautiful. There were actually several cities in between — and a county line.

Before mandatory zip codes, mail delivery was problematic, with letters being misdirected to Orlando proper. Media reports often dropped the “North,” thinking it was simply the north part of Orlando. Others found it difficult to tell visitors how to find the town, requiring them to explain that it is north of Casselberry and east of Longwood lest they end up in College Park or Formosa.

The movement for a new name first gained widespread traction in 1966 when the town council met to discuss it. 71 residents attended the meeting; 69% of them were in favor of changing the name. The problem was that the 49 people endorsing the switch came up with 23 separate opinions for what the new name should be!

To gain a clear consensus, the council decided to pick what it felt were the top four suggestions and conduct a “postcard poll” that would determine its municipal identity. Despite the apparent appetite for a revision, townspeople were not satisfied with their options.

There were 249 ballots returned, choosing from possible names: Ranch City, Norlando, Casanolo, Semino, or to keep North Orlando. A slim majority but decisive victory of 51% opted to stay the course. The monicker would live on, at least for a while.

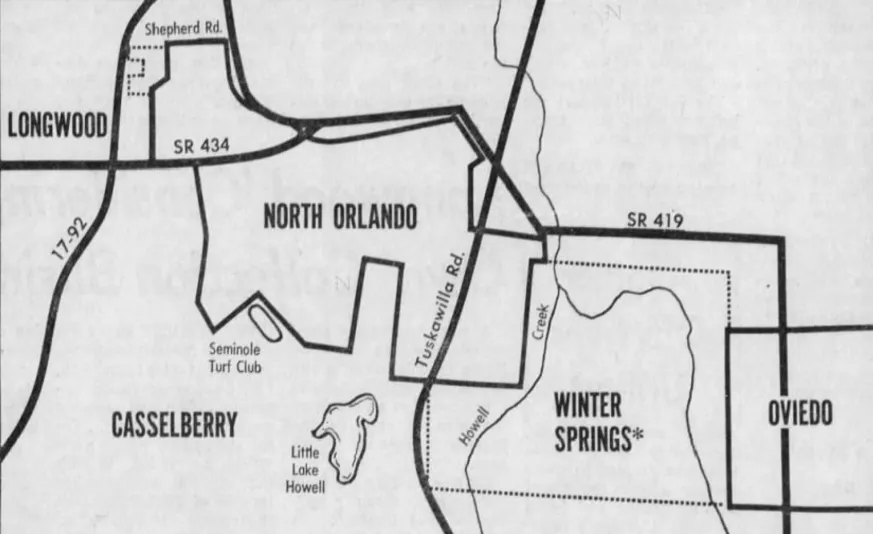

To the east of North Orlando was one of the region’s most extensive tracts of undeveloped land. Developer Bill Goodman sought to change that in 1970. His newly founded Winter Springs Development Corporation acquired 3,500 acres of land, including what became Tuscawilla Country Club.

Soon after ground was broken on the first homes, Goodman approached the North Orlando village council about annexing the vast property. The ambitious board supported the measure, which would double its size and potentially add another 13,000 residents once the development was completed.

When the measure finally succeeded in early 1972, many began to refer to North Orlando as the “sleeping giant.” Though mostly undeveloped, it became Seminole County’s largest city by land area, surpassing Casselberry again despite its southern neighbor’s aggressive octopus-like annexation practices that past year.

The town’s boom continued with a seemingly endless supply of new development plans. The city’s northwest end welcomed the Sheoah Golf Course, backed by world-famous golfer Bruce Devlin. The large community known as The Highlands was also getting underway with its well-appointed clubhouse.

Growth presented a keen opportunity for the village to modernize the statutes of its antiquated charter, which was first drafted by the North Orlando Company. Ripe with the ability to completely reinvent itself, there was a groundswell of support to finally exterminate its unpopular name.

This time, the council decided it would not leave the choice to indecisive townspeople. Instead, after taking opinions from residents, they would make the call and package it in with the rest of the new charter.

A volcano of suggestions once again erupted. The original list of names was joined by a spattering of others: Sunrise City, Norwood, Springland, Seminola, Highlands, Winter Highlands, Woodbury, Woodland, Palm Vista, Midway, Springberry, Spring Highlands, Highview, and Alta Vista. Others submitted in jest names like Paradise Lost, East Longwood, South Sanford, and even… wait for it… North Bithlo.

Sheoah was suggested by city councilman Herb Fox to take advantage of the publicity around Devlin’s new course. Support for that brand evaporated after it was found that another councilman couldn’t pronounce the term, which gets its name from an Australian oak or “she-oak.”

The old favorite standby Norlando was popular among some, including former mayor David Tilson. It would be a straightforward contraction of the town’s current name but still distinctive.

In the end, Semoran was the pick with a 3–2 council vote. The term was a combination of the two counties: Seminole and Orange. The name would better orient folks to its location in South Seminole. It was also already a familiar term given the monicker Semoran Boulevard being assigned to Route 436 through Casselberry.

Local newspapers announced the new charter would reassign the city’s name to Semoran. Outrage by residents ensued! They asserted it was confusing since the town did not border Orange County, nor did Semoran Boulevard come close to its municipal limits. They feared they’d be right back where they started, with people misunderstanding its location.

A week later, the council reconvened. Fearing their constituents’ repulsion for the name Semoran could sink the entire new charter, they quickly reversed their decision. Semoran was assuredly out!

After a more spirited discussion, one suggestion already had significant local recognition. No one in attendance had any objection. In fact, it was said that all quite liked the name.

Suddenly the clouds had parted, and like a rainbow after the storm, there it was — at last, a name all could agree on!

The council unanimously voted and months later, the townspeople affirmed. The new charter redubbed North Orlando as the area it had just absorbed: Winter Springs was born!

4 responses to “Winter Springs was almost called Semoran”

[…] The city life in Orlando was tiring and the couple decided that a slower lifestyle in the country was more their speed. So the couple started looking at properties available in the countryside. In 1973, Juanita saw an eight-acre tract available in the village of North Orlando (renamed Winter Springs shortly after that). […]

[…] hub for fruit and other products. The community was traditionally called North Orlando. After some disagreement, the name was changed to Winter Springs in 1962 after the town annexed a large tract of land from a […]

[…] hub for fruit and other products. The community was traditionally called North Orlando. After some disagreement, the name was changed to Winter Springs in 1962 after the town annexed a large tract of land from a […]

[…] hub for fruit and other products. The community was traditionally called North Orlando. After some disagreement, the name was changed to Winter Springs in 1962 after the town annexed a large tract of land from a […]