Hidden beneath suburban Winter Springs is the old village of Wagner and its once infamous dead man’s curve.

It’s hard to explain how different Winter Springs looked 30 years ago. Today it’s a bustling suburb interspersed by four-lane highways and swarming with sprawl. Three-story apartment complexes and maze-like neighborhoods are devouring the remaining patches of natural habitat.

At the start of the nineties, however, Winter Springs was very much a rural agricultural village. That is not to say no one lived here. The western section of “Old North Orlando” dates back to 1958 and on the east side of town, the original core of Tuscawilla was built in the seventies.

But in between was… mostly nothing.

Heading east from Longwood, State Road 434 was a narrow two-lane country road. Continuing past the 419 intersection, homes quickly evaporated into forest, swamp, cow pasture, farms, and orange groves. There was no Central Winds Park nor Winter Springs Town Center. No Winter Springs High School nor Indian Trails Middle. No post office either.

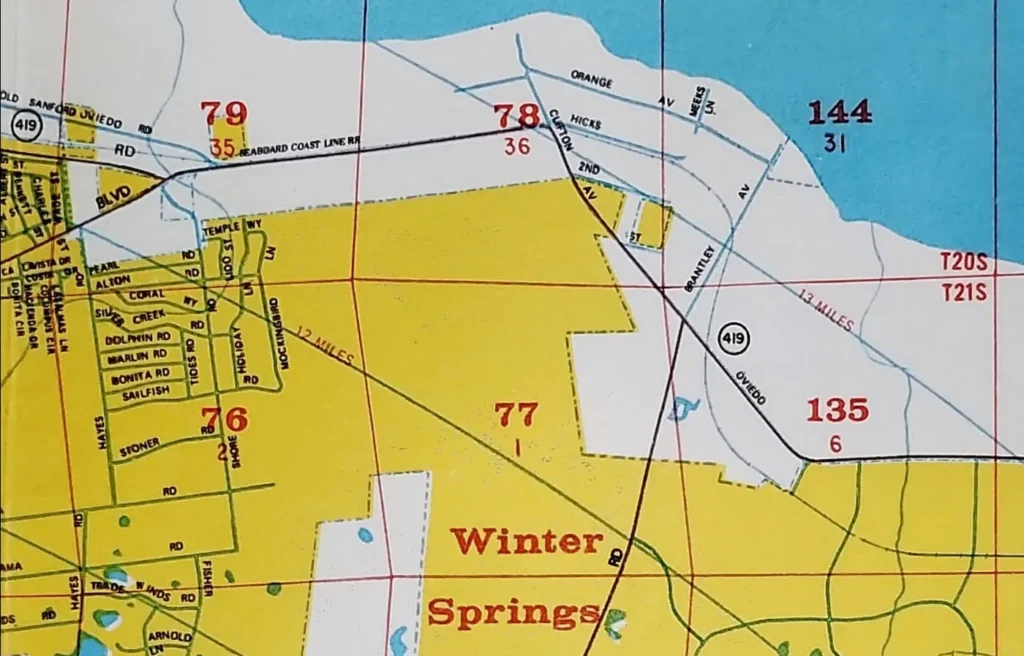

The highway through Winter Springs was once known as the Sanford-Oviedo Road. It started life as a sandy wagon trail, carved out of the native jungle by early settlers shortly after the Civil War.

Orange County Commissioners approved brick paving of the nine-foot wide, 13-mile route in 1912 (Seminole County didn’t split off until 1913). Remnants of this old brick road were recently turned up after a road collapse in Oviedo, and a fragment of the roadway can still be found intact near the flag pole of Layer Elementary.

Besides a few sections where the road was re-routed, the bricks were paved with asphalt in 1927.

Now… imagine yourself driving down this narrow, desolate, unlit path. “Dangerous,” you say? Absolutely. But that’s not half of it! Add in its three sharp “dead man” curves; it was downright fatal! Literally. More on that topic later.

Before there was a city of Winter Springs (or “North Orlando” as it was called from 1958–1972), the area now occupied by Central Winds Park was called Wagner. The origin of that name is debated, but the most likely candidate (in this author’s opinion) is D. G. Wagner, a Sanford-based railroad official promoted to regional manager in 1908.

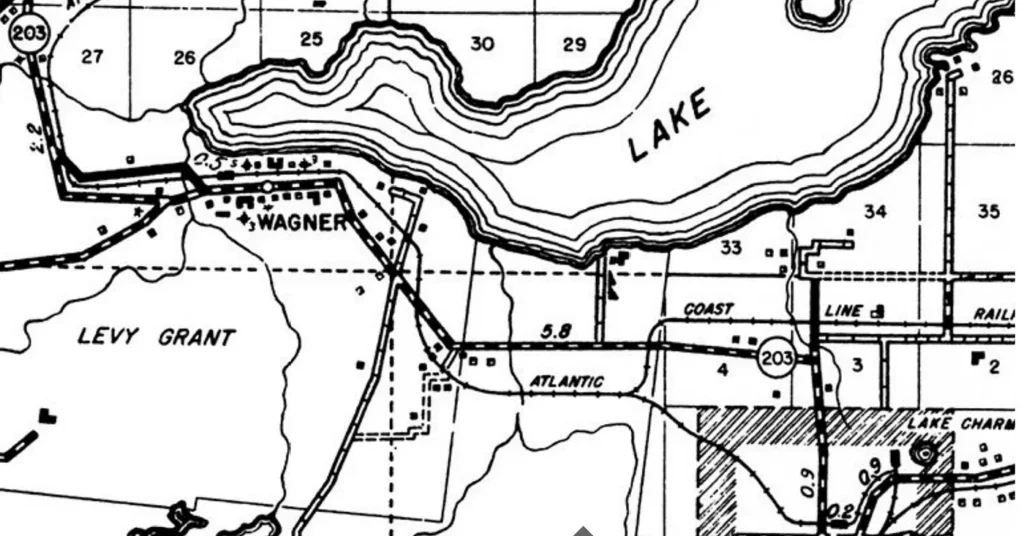

Wagner was located along the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad line, which connected Sanford with Oviedo. The track ran mainly parallel to the highway; it was removed to create the Cross Seminole Trail in 2003. The town’s depot was previously known by various names, including Clifton and Altuvia, but it was re-dubbed “Wagner” in 1911. Near the close of that year, the town was granted a post office — a major status symbol.

Oscar Charles Bryant was the postmaster for the entire 14-year lifespan of the Wagner post office. The tall, dark-complexioned truck farmer was effectively the mayor of the settlement, a population of about 60. In the twenties, the entire village was contained between today’s Choices in Learning School and the Parkstone neighborhood.

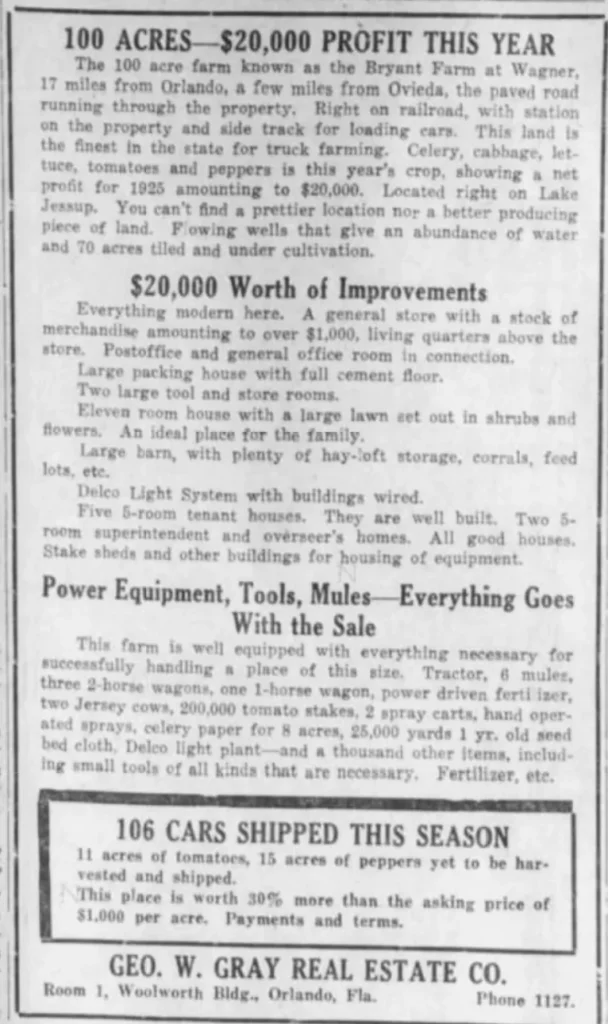

The depot handled few passengers and was never more than a freight stop. The platform and sidetrack were used primarily for loading vegetables from the Bryant Farm. They had great success growing celery, cabbage, lettuce, tomatoes, and peppers with a net profit of $20,000 annually.

Almost everything was part of Oscar and Elizabeth Bryant’s 100-acre plantation. This included the two-story general store (with living quarters on the top) that doubled as the post office, a large packing house, an electric light system, a handsome 11-room estate home, and a half dozen smaller houses for laborers and overseers. Wagner Baptist Church operated out of Bryant’s home, starting on March 16, 1923, with Reverend E. A. Milton.

However, Bryant’s health began to fail in 1925 and with his decline, the town’s prospects waned. The post office and church closed that year. Bryant put his large estate on the market and moved to Sanford with his wife and newborn baby, Mary Elizabeth. Bryant died in 1928 in a Jacksonville hospital and was buried in Sanford. He was only 48 years old.

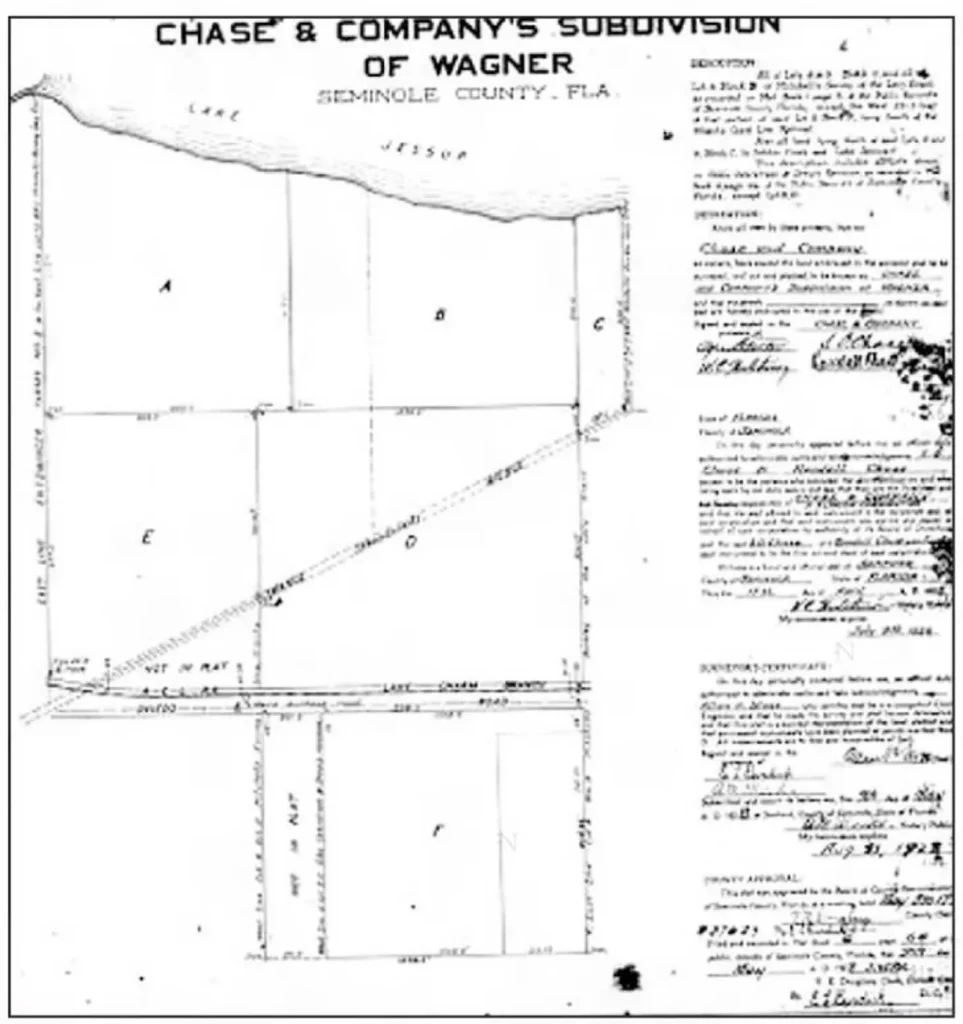

Chase & Company snatched up the prime parcel and added it to their local empire, later platting it as a subdivision.

If Chase & Company planned to sub-divide the property and turn it into a legitimate townsite, those visions crashed with the close of the Great Florida Land Boom and the onset of the Great Depression. However, the agricultural behemoth operated the property successfully in producing cabbage, peppers, and other vegetables for decades.

The old underground irrigation system is buried under feet of concrete and dirt fill in the Parkstone subdivision. A tubular clay tile system was laid throughout the property and linked to artesian wells. Farmworkers could water one section or another by blocking up strategically positioned holes. When they received a lot of rain, the plugs would be removed and the flow reversed to provide ample drainage.

Seminole County opened a public school for the children of Wagner’s black laborers in 1931. Gertrude Davis was hired as its first teacher. The 25-year-old made $50/month to mentor the 18 students at the Wagner School.

The one-room wooden schoolhouse was located where the Winter Springs City Hall sits today. It was the heart of the community for the mostly black citizens of Wagner during the thirties and forties, acting as a church sanctuary on Sundays. The school was closed in 1950 when it merged with Oviedo.

In 1958 the incorporated Village of North Orlando (renamed Winter Springs in 1972) sprang up as a planned development just west of Wagner. Between its growing prominence and the fading importance of truck farming communities, the collective memory of Wagner as a place withered. But one relic remained: “Wagner’s Curve.”

Wagner’s Curve was the most intense of the three sharp turns along the road. Old-time residents still recall how the 90-degree bend on the dark, narrow highway forced drivers to slow down to 15 miles per hour to make the turn safely. Dense trees lined the road, blinding motorists to oncoming traffic.

The bend continued to widely be called “Wagner’s Curve” by locals well into the nineties. Though nobody named Wagner lived there, it was typically used in the possessive form rather than the more correct “Wagner Curve.”

Up until 30 years ago, there would be a terrible accident here every few years. Careless drivers would not heed the signs and flashing lights urging autoists caution. Too often, they would drift into a head-on collision, flip, or simply miss the turn entirely and end up in the orange grove. At least two such accidents proved deadly during the eighties.

In 1984 passenger Roger Riggs of Sanford died in a 3 AM accident when the driver took the curve too quickly, and slide off the road, with the car landing upside-down on the railroad tracks.

On New Year’s Eve 1988, two families were in a caravan, leaving on vacation to Hilton Head, South Carolina. Phillip Seeger was driving the lead vehicle when they approached Wagner’s Curve around 7:30 AM. A large truck carrying massive concrete pipes approached in the other direction. The driver missed the curve, braked, fishtailed, and landed on its side. One of the on pipes rolled free, smashing into the car. The 37-year-old father was killed, and his wife and two daughters were hospitalized.

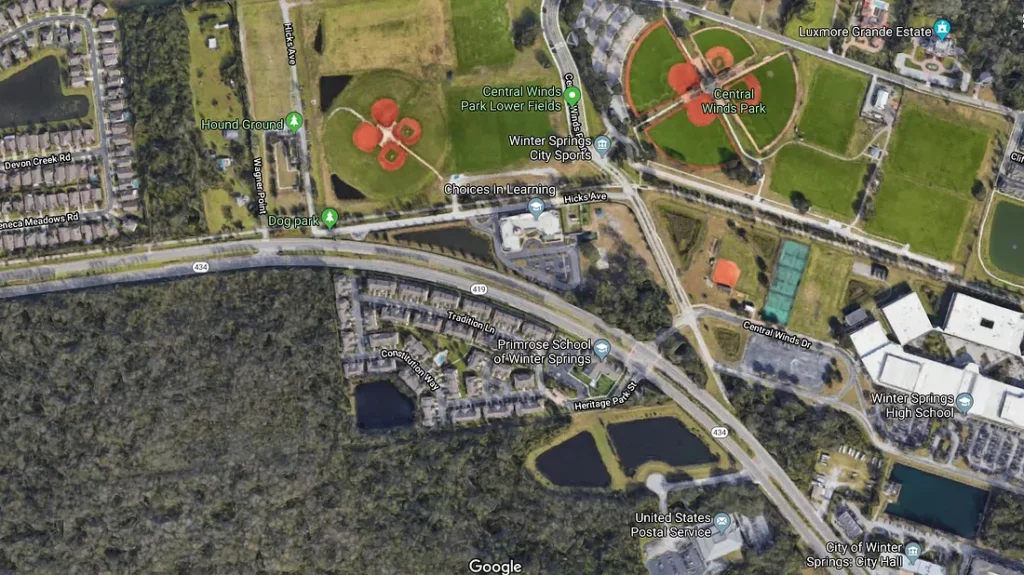

In reaction to the tragedies and surging traffic, public outcry grew. In 1990 a 32,000-square-foot post office was opened near the curve. The City of Winter Springs began constructing the 59-acre Central Winds Park in 1991, which opened in 1992. This prompted louder demands for state officials to round off the tight hairpin turn.

After many delays, the road was moved slightly southward with a less severe angle in late 1992, allowing room for the Central Winds entrance. Then, finally, in 1996, the Department of Transportation widened State Road 434 to four lanes and softened Wagner’s Curve to a gradual arc, allowing cars to safely maneuver at 50 miles per hour.

Today only the tiniest segment of the old road remains in front of Winter Springs High School, which opened in 1996. The actual turn can be imagined at Hicks Avenue and Central Winds Parkway (between Choices in Learning and Winter Springs High School). The Florida Trail has now replaced what would have been the railroad. The orange groves are now ball fields.

Wagner Curve had two sister curves further east. The most clearly visible is the intersection of DeLeon Street and Hammock Lane, near Black Hammock. The little dead-end “road to nowhere” was the original highway pre-rounding.

Until recently, a really cool section of the old highway survived just east of Tuskawilla Road. It was a great trip back in time, hidden just off the modern highway. At this curve was another old train depot called Tuskawilla Station. Sadly signs of either were destroyed in 2017 with the construction of the Tuskawilla Crossing neighborhood.

While we miss the romance of the simpler times, we can be thankful that we no longer have these treacherous nuisances to deal with!

If you enjoyed the article, give it a like and share it with friends. I hope that next time you pass Winter Springs Town Center and zoom by Central Winds Park, you’ll think about old Wagner and its curve!

2 responses to “Rounding Wagner’s Curve”

[…] Moss and Edgemon. Only a few farms were east of 419 until you got to Oviedo. Highway 434 was a two-lane road with sharp curves. Tuskawilla Road was a dirt path. There was no neighborhood, golf course, or country club in […]

Very interesting! We moved to Winter Springs in 1982 and remember many of the places and instances mentioned in your article. My husband John is a former mayor of Winter Springs.

We have enjoyed living here these many years and raising our family here. Thank you for your research and for making it available!