The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s is notorious for lynchings and bigotry. And that dishonor is well-earned, of course. However, the hooded order was involved in more than simply terrorizing blacks, immigrants, Jews, and Catholics.

In those days, the Klan was a civic institution in Central Florida. Its roster numbered in the thousands from every walk of life — even many high-ranking politicians and pastors. With incidents like the Ocoee Massacre in 1920, its influence during this period is hard to exaggerate.

Longwood of 1921 was a speck of a town, having a population of barely over 300. It had three churches (Christ Episcopal, First Baptist, and Corinth Baptist [black]), a handful of stores, a post office, and a two-room schoolhouse. The Women’s Civic League ran a small library next to the hotel.

The main artery through town was the nine-foot-wide Dixie Highway. The brick-paved road ran north to Sanford and south to Altamonte Springs (now County Road 427). The entire town was between what is now Palmetto Avenue and State Road 434.

The main road heading west was Warren Avenue, which was then called Palm Springs Road. On the south end of town, travelers could head east on Oviedo Road (now State Road 434).

It was very tempting for speed demons to ignore half-mile-wide Longwood. They would roll through intersections without stopping and ignore speed limits with impunity. Locals considered the Palm Springs Road intersection especially dangerous, with the town’s few commercial buildings centered between there and Markham Road (Church).

Town marshal, Arthur Raymond Stiles, decided that he was going to start cracking down. The 32-year-old was Longwood’s one-man police force, and he began posting himself at the busy crossroads. He flagged down speeders to issue warnings or citations; it is suggested that he could be convinced to show leniency for a little $5 pocket-padding.

Reportedly the trouble started on a Wednesday night in August 1921. Stiles stepped into the road to wave down a speeding motorist. The driver did not stop and nearly flattened the officer. Moments later, another car full of young men approached with no lights. Stiles flagged the group over and lectured the driver about his recklessness. The men were not amused and debated with the marshal on his unequal enforcement of traffic laws.

There was another rumor that the officer could be similarly enticed to look the other way for bootleggers. Alcohol was made illegal in the United States a year earlier.

The next night, around 9:30, Stiles sat on the porch of one of Longwood’s two general stores. The officer was with several locals when, suddenly, their conversation was interrupted when two speedy cars flanked the building.

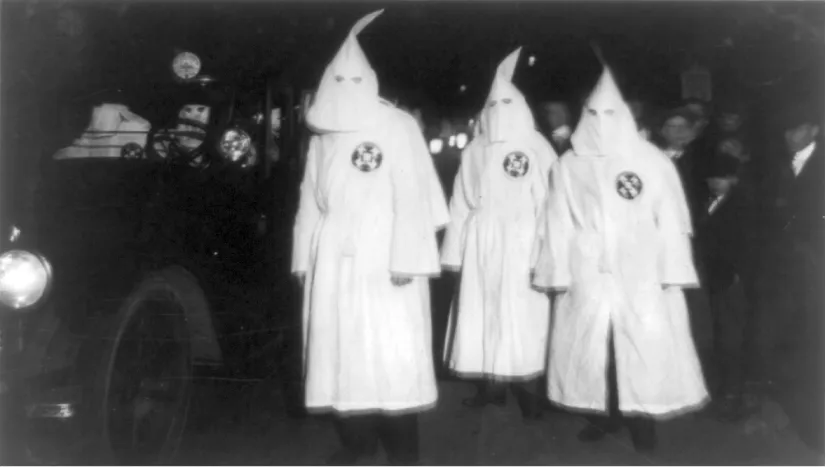

It was, presumably, the men Stiles had pulled over the day before. This time they brought more friends. Sixteen klansmen in full regalia filed out of the vehicles, guns trained on the marshal.

Seeing them coming, the lawman tried to slip out the back of the store, but his leap failed to clear the chicken wire. Entangled, he quickly found himself surrounded by the white-sheeted outlaws.

“I was covered with a revolver,” Stiles told the Orlando Sentinel reporter, “and ordered to throw up my hands, which I did. I was then relieved of my gun and rushed to a waiting automobile. Every one of the party were armed with a gun.”

One of the klan members hung around the front, preventing the officer’s buddies from interfering with the plot. Stiles was restrained and tossed into the back of one of the vehicles. Before they left, a klansman warned the citizens not to follow but assured them the marshal would be returned alive.

The costumed mob sped south down the Dixie Highway before turning left onto Oviedo Road. The moonlit dirt path was desolate, and the vehicles finally pulled off into the woods about five miles outside of town (probably near Tuskawilla Road).

They unloaded Stiles and threw him onto the ground, roughing him up only slightly. With guns to his head and descriptive words lobbed about the harm that could befall him and his family, the klavern instructed Stiles that he would resign immediately from his position. Or else.

After rendering their forceful advice, the mob returned the marshal’s emptied pistol. They instructed him to stay on the ground until a certain signal was given — perhaps a gun fired into the air — and then, as quickly as they had come, the party sped westward.

Upon hearing the signal, the officer arose. He dusted himself off, oriented himself, and started the long walk back to Longwood. He arrived home just after midnight, greeted by his thankful wife, Mabel Saphorina Hartley Stiles, and their three children (aged 7, 5, and 3).

The next day, Stiles marched into Mayor Henck’s office and turned in his badge and gun. Despite the town executive’s protests, the marshal was set on taking the recommendation of the KKK. He resigned.

Although there is no indication that the events are related, Arthur’s wife, Mabel, died less than two weeks later at age 37. Reportedly, this untimely death came after several months of illness.

Private citizen A. R. Stiles raised their three children in Longwood, eventually remarrying. He never again entered into politics or law enforcement.

Stiles passed away in 1954 and was buried with Mabel in Longwood Memorial Gardens cemetery, along with their two daughters, Georgia and Ethel (who both died in 1981). Their son, Carl, died at 95 years old in 2011 and is buried in Umatilla. Mabel was the granddaughter of pioneer Lee Jackson Hartley, Sr. The family were the first permanent white settlers in the vicinity of Longwood, settling on the north shore of Lake Fairy in 1870 — Edward Henck didn’t arrive until two years later.