“Here will soon be one of the busiest and most populous towns in Florida,” insisted one October 1925 announcement. Another advertisement boldly proclaimed the new Highlands County settlement would “become the trading center of the greatest and most profitable truck-farming, poultry-raising and dairying section in the South.”

Such boasts were anything but rare in the 1920s at the peak of the Florida Land Boom. However, these claims were given substantial credence by the reputation of its sponsors: Glenn Hammond Curtiss and James Bright.

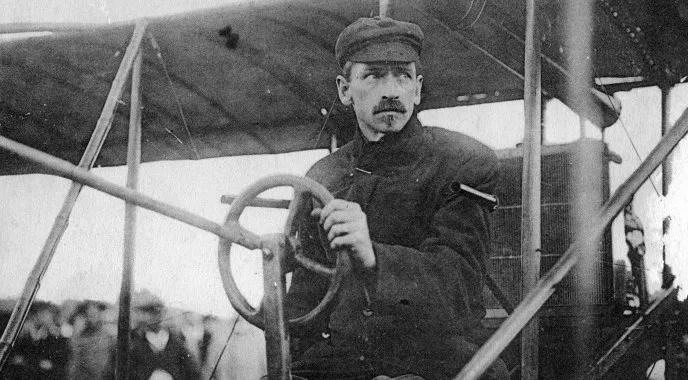

The friends and business partners were each famous in their own right. Curtiss (though today far less known) was more successful than the Wright Brothers as an inventor, entrepreneur, and pioneer in the world of aviation. Bright was a prominent cattleman, having acquired a ranching empire and contributed many important innovations to the bovine industry in Florida.

The duo met in 1916 and quickly started a business relationship. Together they founded the Curtiss-Bright Company in 1920 to turn portions of their vast ranch holdings (which numbered in the hundreds of thousands of acres) into thriving cities.

Their town-building debut was an unmitigated success. They launched the municipality of Hialeah in 1921; it quickly rose to become one of the fastest-growing cities in the nation and a regional hub for recreation. Today it is Florida’s sixth-largest city.

As a sequel, they platted the South Florida cities of Opa-locka and Miami Springs — then called Country Club Estates. These three Curtiss-Bright developments made the already wealthy men tens of millions of dollars richer. They cemented them as revered tycoons of Florida real estate and fixtures in Miami high society.

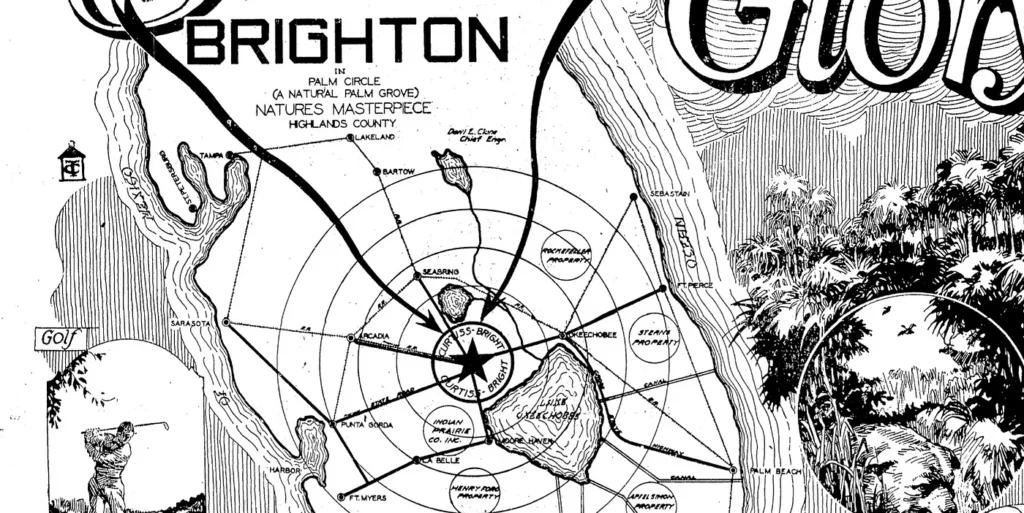

Glenn Curtiss first saw the Brighton area from the sky. He noticed the smoke from a nearby Seminole village. A vast region of tall grass covered what was known as the Indian Prairie. It seemed an ideal farming hub since it sat on relatively high ground above Lake Okeechobee (safe from hurricane-related flooding). At the time, Florida imported most of its meat, dairy, and vegetables, so there was a considerable demand for local agriculture to feed the state’s exploding population.

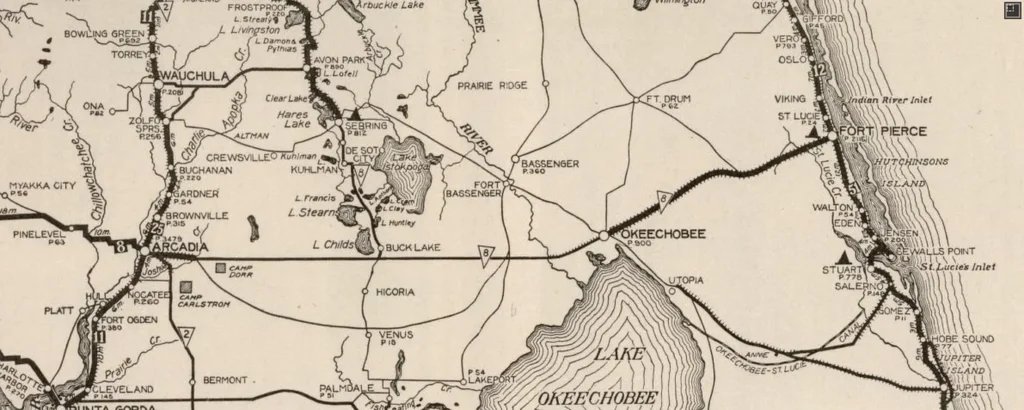

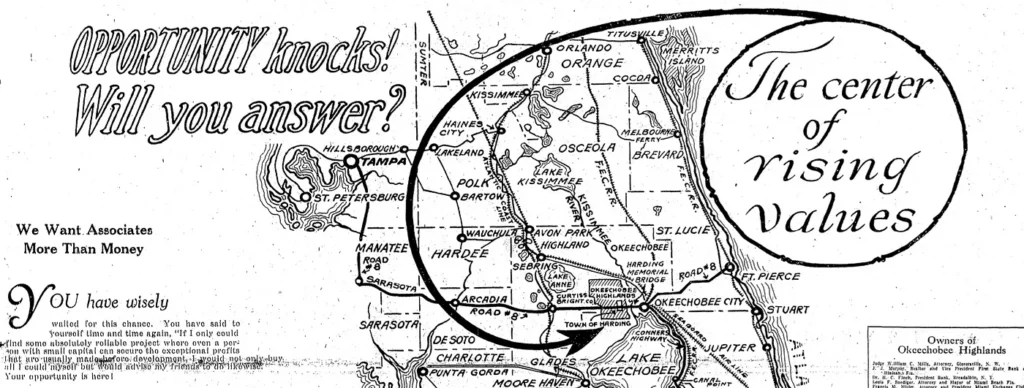

Despite being even more desolate a stretch of land then than it is today, Brighton was considered strategically located, equidistant from both Florida coasts. It was a relatively short drive from Sebring to the west and Okeechobee to the east. With the opening of the Harding Memorial Bridge over the Kissimmee River, the east coast could be easily reached via State Road 8 to Fort Pierce or Conner’s Highway along Lake Okeechobee to Palm Beach.

In 1925 the Curtiss-Bright Company purchased 28,000 acres (44 square miles) along both sides of State Road 8 — now Highway 70 — straddling Highlands and Glades Counties. They would later expand that footprint to over 70 square miles.

From their aerial vantage point, Curtiss and Bright spotted a nearly perfect ring of palm trees encircling what is now the intersection of Highway 70 and Country Road 721. They hand-picked this spot to become the town site and commercial center for the great agricultural powerhouse they envisioned. It was dubbed Brighton in honor of its co-founder James Bright.

Wasting no time and sparing no expense, they got right to work. The first initiative was to tame the wetlands and provide irrigation by digging dozens of miles of canals. The second goal was typical of any proposed settlement at the time: construct a hotel. But not just any hotel!

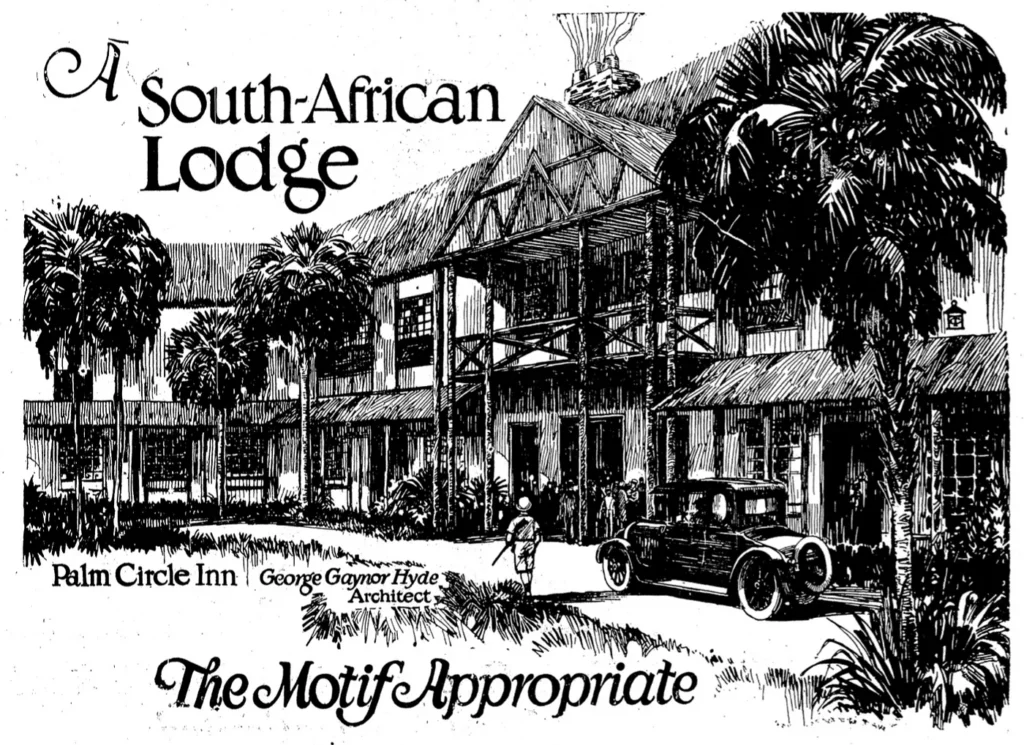

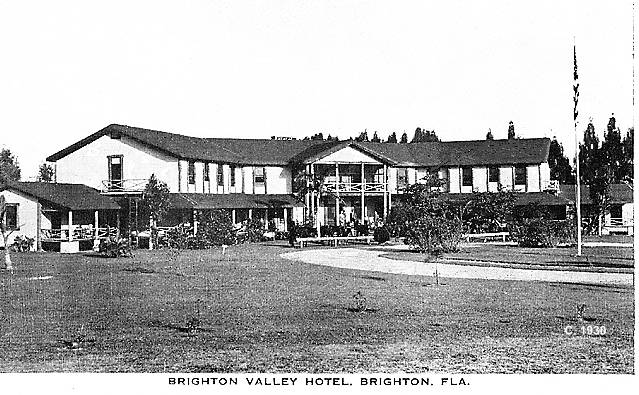

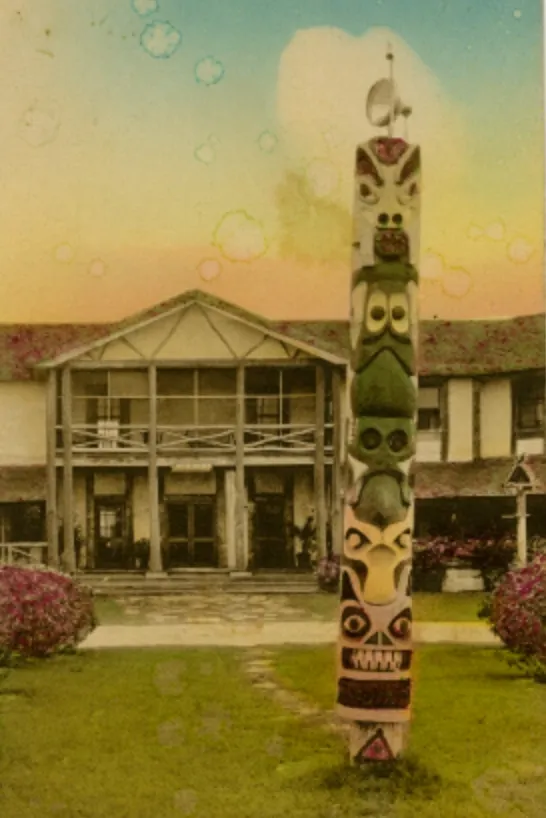

The 83-room luxury hotel was a lavish, rustic-themed lodge with an identity crisis. The Palm Circle Inn opened on March 24, 1926. Two years later, it was rebranded as the Brighton Valley Hotel until 1936 when it became the Brighton Lodge and, finally, the Rainbow Ranch during its final transformation as a camp retreat from 1939 until 1941.

In some advertisements, the resort was billed South African-themed to match the savannah-like Indian Prairie grassland. Other times, they sought to embrace the style of the nearby Seminole Tribe. However, the authenticity of either influence was muddled by the totem pole out front and the southwestern-themed Navajo memorabilia that decorated its grand lobby.

Regardless of the nebulous motif, it was a true Central Florida oasis that became the de facto gathering spot for regional meetings and conventions. It was known far and wide for its attractions, amenities, meals, and excursions. The Brighton Valley Hotel became a favorite getaway for Florida’s elite and hosted famous guests like Charles Lindberg, J.C. Penney, and even President Herbert Hoover.

Visitors came to Brighton from far and wide. The resort featured day trips for fishing and exotic hunting: fox hunts (with a fleet of hounds raised nearby), alligators, hawks, bears, and wild cats (panthers, bobcats, and lynx).

Besides the guided outings, the resort featured plenty of on-campus activities. These included archery, golf, and an aviation field. In 1928 a well-appointed stable of horses was added and the Brighton Valley Hotel was heavily marketed as the only dude ranch east of the Mississippi.

The hotel was also well-known for its artesian well, which is an ever-flowing well where the water feeds up to the surface by the natural pressure of the aquifer without the need for a pump. The well provided a continuous flow of fresh water into a stately pool, an extremely popular and novel attraction during the era. The teenagers and young adults especially flocked to its waters for hours.

Besides vacationers and high society guests, area residents from up to an hour away in Sebring, Avon Park, and Okeechobee would make regular weekend trips to the resort. Parties and dances were often held there, and non-overnight guests were free to dip in the pool, which overlooked an extensive collection of animal exhibits.

The Brighton Zoo was a full-fledged zoological attraction in and of itself. It featured monkeys, kangaroos, birds, porcupines, tortoises, a bear cub named Teddy, and other exhibits.

The efforts at the facility gained notoriety among zoologists. The zoo was the first to successfully breed monkey families in captivity north of Havana. And its excellence was recognized by the New York Zoological Society in November 1928, when it was selected to host its Galapagos Island tortoises in a breeding program to help save the massive reptiles from extinction.

Before the zoo’s closing in 1931, the zoo had 20 monkey escapees. Their flight to freedom took them into the nearby woods surrounding the resort. Each night the primates would return to the hotel in search of dinner, only to vanish back into the vegetation after their meal. This routine continued for a year until they were finally recaptured and returned to captivity.

In 1927 Bright used his significant influence to start a campaign to form a new county with Brighton as the county seat. The proposed county would have cut off the portion of Highlands County east of Lake Istokpoga from Fort Basinger southward to the banks of Lake Okeechobee in Glades County.

Even though Highlands and Glades Counties had only recently been formed — being split from DeSoto County in 1921 — the proposal reportedly had unanimous support from the (very sparsely populated) residents within its proposed borders. However, area newspapers universally panned the concept, especially in the Sebring White Way.

The biggest knock on the new division seemed to be that it would remove about a third of the land and population from an already barren Glades County. Although there were several promising settlements in the vicinity in 1927 (such as Elderberry, Allentown, Alford City, Winifred Estates, Lennox, Fort Basinger, Cornwell, and Harding), today, the only existent population centers in the would-be county are Lakeport, Buckhead Ridge, the Brighton Seminole Reservation, and a few scattered mobile home parks near the Kissimmee River in Highlands County. So, in retrospect, the legislature probably made a good decision in leaving the county lines as-is!

Between 1925 and 1927, people realized the Florida land boom was somewhat of a ruse. The rapid inflation of prices was unsustainable and paper millionaires started to find they could no longer unload their “sure thing” investments. The bubble had burst. Shortly thereafter, the rest of the nation found Wall Street had a similar bubble, which imploded the nation right into the Great Depression in 1929.

These severe headwinds ultimately killed the visions of many of the new developments starting around the same time as Brighton. Most of them never got off the ground; however, most developments did not have the determination and financial backing that Curtiss and Bright afforded.

To be sure, the lack of ample settlers and liquid finances did seriously hamper Brighton’s prospects. The Curtiss-Bright plans to pour tens of millions of dollars into the project had a severely slashed budget, but things continued to move forward.

Besides the hotel, the town had a general store, service/filling station, offices, cold storage, ice manufacturing, residential water service, post office, chamber of commerce, and even a power plant. A two-story school building was constructed at Brighton in 1926 as part of the Highlands County public school system, serving the town’s approximately 150 residents and those from surrounding agriculture-based settlements.

The company dug more than 37 miles of drainage canals to facilitate farming. Many miles of access roads were created for the area farms. Curtiss-Bright helped to construct seven miles of road through their property, what is today County Road 721, running south from State Road 8 (State Road 70) into Glades County to State Road 38 along Lake Okeechobee via the Brighton Seminole Reservation.

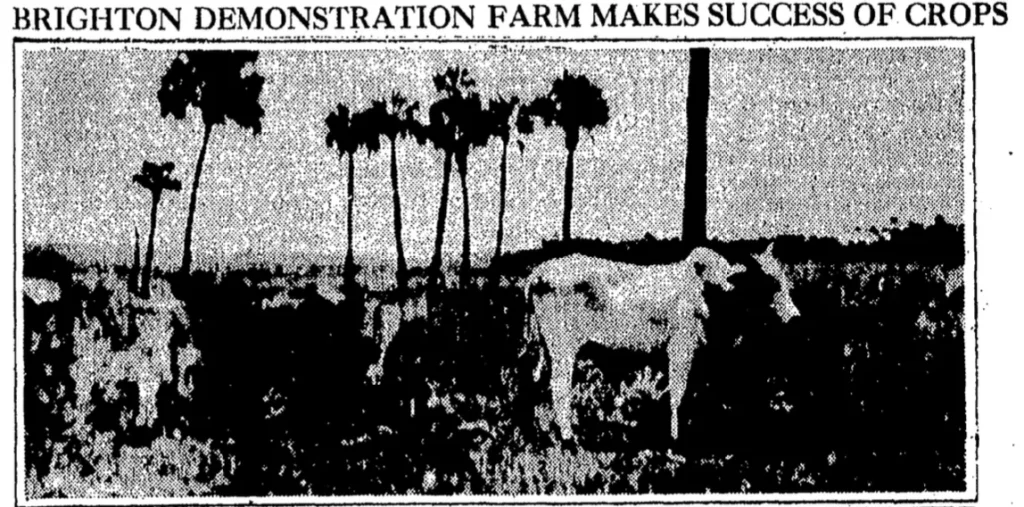

Brighton Valley Farms was the largest of the area ranches. It was owned by the Curtiss-Bright Company. It contained tens of thousands of acres of cow pasture with native and imported grasses, which thrived and grew up to ten feet tall. Bright was the first to introduce Brahman bulls to Florida and began breeding significantly larger cattle varieties. By 1930 the ranch had over 1,500 head of cattle and at least 100 hogs.

Other settlers had great success with dairies and poultry. Six privately-owned dairies had herds totaling around 750 Jersey and Holstein cows, the largest being Palm Circle Dairy, owned by Jess Oller. The biggest of Brighton’s five poultry farms was owned by J.D. Leverett. At its peak, it had a flock of 7500 leghorn chickens and 3500 domestic turkeys, guinea hens, ducks, and geese numbering in the hundreds.

Thousands more acres were owned by 35 individual growers in the area. They raised various crops, including Irish potatoes, sweet potatoes, lima beans, onions, sugar cane, peas, green beans, watermelons, strawberries, citrus, blackberries, pumpkin, beets, carrots, cabbage, tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, and other fruits and vegetables. In 1930 Dixie Sugar purchased several hundred acres to raise sugar cane and constructed a 650-ton cane syrup manufacturing plant in Brighton.

Brighton’s small-time farmers had a prominent ally and an accessible market for their products. All of the sales were handled through the Curtiss-Bright Company. They would produce, store, market, and transport the eggs, milk, crops, and meat products under the Brighton Valley Farms brand. The products were popularly sold primarily in Miami, with fresh shipments arriving every morning and trucked in overnight from the cold storage at Brighton. All farms, regardless of size, were given the same price for their produce.

Death of Glenn Curtiss

On July 23, 1930, the famed aviator and Brighton co-founder, Glenn Curtiss, died unexpectedly in Buffalo, New York, after complications from an appendectomy caused a blood clot near his heart. The country was stunned and his death dominated the front pages of newspapers nationwide.

Curtiss-Bright officials immediately promised that nothing would change in the company’s personnel or its development plans in Florida. Despite these claims, things slowly unraveled significantly as the Depression deepened in 1931.

In January, the Brighton Zoo was almost wholly disassembled, with many of its exhibits being sent to the Opa-locka Zoo (also owned by the Curtiss-Bright Company). Then in June, Florida Power and Light purchased Brighton’s power plant and electrical system .

By this time, the vision of a thriving community at Brighton had long since been put on hold due to the entire nation’s financial tumult. However, as a novelty tourist destination, the Brighton Valley Hotel continued to stay afloat with streams of still well-to-do society folks, honeymooners, and business groups. The dude ranch and hunting expeditions remained popular getaways.

However, the company’s divestitures continued, and on August 26, 1931, the Brighton Valley Hotel was sold to B. H. King. The inn limped along from there, primarily for its dude ranch and bed and breakfast. It was sold to Mary Barbour Blair of Chicago in 1935 and was renamed the Brighton Lodge. It was operated sporadically during the following five years. After relocating to Miami late in her life, Blair began to shop the hotel at various non-profit organizations seeking to put the property to good use rather than languish just to pass it on to someone after she died.

In July 1940, she deeded the 88-acre Brighton Lodge to the Miami YMCA, which immediately took over management of the money-losing operation and renamed it Rainbow Ranch. Various groups began to use it for retreats and youth camps.

At that time, the property’s main building featured rosewood walls and included 34 bedrooms, a dining hall, a kitchen, a library, and the grand lobby. The lobby accommodated meetings of 100 people and was flanked by dual staircases with a vast rustic fireplace at its center. It was lined with an intriguing collection of antiques and curiosities from around the world, including a saddle once owned by Pancho Villa. The swimming pool, shuffleboard and tennis courts, horse stables, five log cabin dormitories, and various other outbuildings rounded out the amenity-rich retreat.

Fire Destroys the Lodge in 1941

In the wee hours of July 14, 1941, the campers at the Rainbow Ranch were abruptly awoken by the smell of smoke and screams of FIRE! By the time they were roused from their beds at 4:30AM, the flame’s sinister fingers were already menacingly tapping on the second-floor dormitory windows.

Frantically the 23 boys from the Miami YMCA and other attendees raced out of the building, grabbing whatever they could hurriedly carry and the clothes on their backs. Some escaped the inferno, only wearing underwear or pajamas, and needed to borrow shirts or shorts from other campers.

Helplessly they watched as their new camp facility, only in its first summer of use, lit up the sky over the Indian Prairie. The entire building was quickly engulfed. When the sun rose to their left, nothing but the brick chimney that formerly anchored the dignified main lobby remained.

Local farmers and residents gathered with the campers in disbelief. Though already far removed from the town’s promising heyday, the lodge was the community center and the stalwart symbol of its identity. The Brighton citizens comforted the boys and fed them breakfast before their long sad trip along the shores of Lake Okeechobee and back to Miami.

The Miami YMCA relocated camp facilities elsewhere, but the Brighton experiment was never re-attempted. Some area residents, farms, and dairies remained, but the Lykes Brothers picked most of the depression-devalued lands (including charred remains of the lodge).

The seven brothers profited handsomely from their shrewd investments and built an impressive multi-industry conglomerate. Despite selling off most of the family’s other holdings in the 1990s and 2000s, the Lykes Ranch is still one of the largest contiguous properties in the country. Its 337,000 acres spanning Glades, Highlands, and Okeechobee Counties include nearly all Curtiss-Bright territory and a vast amount more.

What would have happened if the trifecta of the disintegration of the Great Florida Land Boom, the Great Depression, and the death of Glenn Curtiss had not colluded against Brighton? It’s certainly hard to say for sure. But there is a good possibility that Brighton could have ended up the power broker city of the Lake Okeechobee region and the favorite tourist destination of the Kissimmee River Valley.

Today very little is left to mark the town. Virtually all of the former buildings and facilities have vanished. The First Baptist Church of Brighton, the Lykes Brothers office (located on the old Brighton Valley Hotel campus), and a few scattered homes remain. Most famously, the town lives on via its namesake Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation and 27,000 square-foot casino, about seven miles south of the old town site.