How did Orlando get its name?

Over the past century, probably a hundred historians have debated the name origin of the City of Orlando. “So,” I thought, “why not become 101?!”

I will reveal some new tidbits and an angle not previously suggested. First, I’ll lay the backdrop, then we’ll discuss various origin stories that have been told, and then finally give you my theory. Jump to the end if you want to cut to the chase; read on if you want to follow the investigation.

Orange County in the 1850s

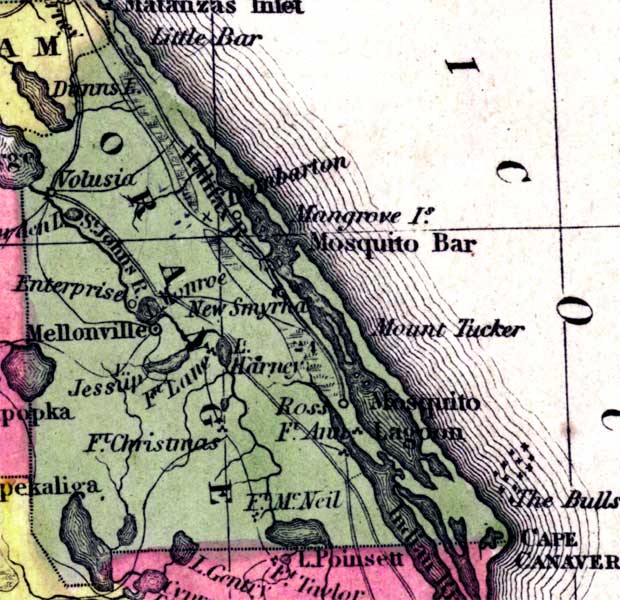

Only a few hundred people lived in Orange County in 1850. The vast area also contained Seminole, Volusia, northern Brevard, and parts of Osceola, Lake, and Flagler counties.

The Seminoles had been expelled completely, which opened the inland to white settlement. Railroads were three decades away, so the main thoroughfare was the St. Johns River and its steamboat ports. The communities of Enterprise (Deltona) and Mellonville (Sanford) were the centers of population and commerce. Outside of these two ports there was nothing resembling a town.

There is another article’s worth of drama here that is relevant, but not essential. I’ll give you the “TL;DR” version and reserve the rest for another day.

Between 1854 and 1856, the State trimmed Orange County’s borders to essentially just modern Orange and Seminole counties. Residents called for a referrendum to decide where the county seat would be. Should it remain in Mellonville (or its “suburb” of Fort Reid), at the far northern end of the county? Or should it be in one of the other small but growing settlements: Oakland, The Lodge (Apopka) or Fort Gatlin/Jernigan (Orlando)?

As can be expected, people generally voted for whichever one was closest to their home. Because of its larger population, Fort Reid/Mellonville was considered a lock. However, through some smooth political maneuvering, Fort Gatlin (in the southern part of the county) pulled off the upset.

Only one problem… there wasn’t a town in southern Orange County. None at all! Where would they even build the courthouse? One possibilty was near the remnants of decommissioned Fort Gatlin. Another logical choice was on Aaron Jernigan’s property on Lake Holden. He settled there in 1844, established a trading post, and was granted a post office bearing the name “Jernigan” in 1850.

Unfortunately, Aaron had landed in legal hot water in recent years and made a number of enemies. A growing contingent of settlers, especially the new comers, wanted no affiliation with the Jernigan name.

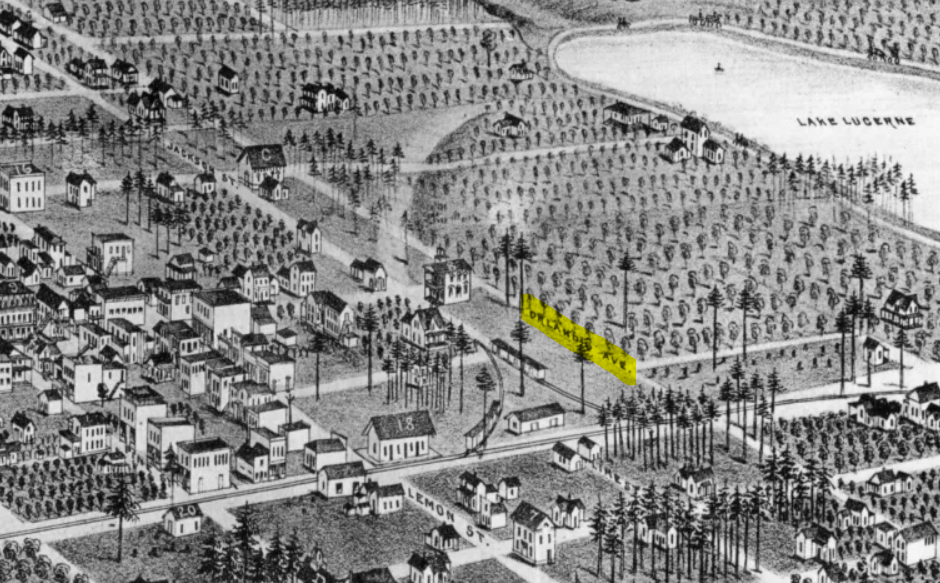

John Worthington was one of those people. He settled along the Fort Mellon-Fort Gatlin road around 1850, building a log home and a trading post not far from Lake Eola. Judge James Gamble Speer and his wife Isophenia Cleopatra Ellington Speer moved to the area in 1854. They acquired substantial land holdings throughout the county–including what is now downtown Orlando, adjacent to the Worthingtons.

Most of the Speers’ wealth came from Isophenia’s step-father, William Harris Caldwell, a plantation owner from Alabama. Judge Speer offered four acres for the new courthouse and town square. When the official plat was filed, it was labeled the Town of Orlando. Worthington was named postmaster of the Orlando post office.

A new town had been born virtually over night (at least on paper). As we know, it would grow into one of the largest cities in the state of Florida. But when they decided to throw out “Jernigan” or “Gatlin,” where did the name “Orlando” come from? At last, we’ve made it to one of the greatest debates in city history!

Name Origin Legends

Theory 1: Judge Speer Loved Shakespeare

During the mid 1800s public schools were becoming standard. The works of William Shakespeare were universal reading curriculum and commonly performed as entertainment. Understandably, many people grew up loving these classic works. One of the most popular was “As You Like It,” which involves a heroine named Rosalind and the comedic wooing of her love interest, Orlando.

Most sources, dating back to 1884 newspaper reports, credit Judge Speer with coming up with the town’s name and cite his love of Shakespeare. In the 1915 book “Early Settlers of Orange County” by C. E. Howard, the author says unequivocably, “the question of a name came up and was named ‘Orlando’ by Judge Speer for one of Shakespeare’s characters.”

Some people point to Rosalind Avenue as evidence. It is a main road in downtown Orlando that fronts Lake Eola. However, the link is indirect. It was once called Speer Avenue, then West Street, before being named Rosalind in 1919. It was given this name after the Rosalind Club, a womens’ social club founded in 1894, moved his headquarters there.

The organization was originally named Ladies Social Club of Orlando. Then re-dubbed as “Wimodaughsis” (wives, mothers, daugthers, sisters). And then finally as the Rosiland Club, around 1896. This name was a direct reference to the play. “Rosalind” being female pairing of “Orlando,” just as these women were to the men of Orlando. Is that definitive proof of the town’s name origin? Not exactly, but it’s at very least strong circumstantial evidence.

This theory is backed up by multiple descendents of the Speer family. James P. Speer II, great grandson of James Gamble Speer, reiterated this to the Orlando Sentinel in 1998. “He told us,” referring to this grandfather, “his father had named the civilian settlement near the fort ‘Orlando’ after the character of that name in Shakespeare’s play.”

Theory 2: A Soldier named Orlando

Case closed? Not so fast. The most popular account is that the town was named for soldier during the Second Seminole War (1835-1840). Orlando Reeves, they say, gave his life defending his camrades. Some versions say it was Orlando Jennings or Orlando Reed.

The story goes like this… south of Lake Eola, there was a small spring not far from the Fort Mellon-Fort Gatlin Road. It was a popular camping spot for soldiers and pioneers that needed a stopover between the forts. It was a slow and difficult journey back then.

Somewhere between 1837 and 1840, one such group included Orlando Reeves and some other friends (including a man named Simmons). This was not long after the attack on Camp Monroe (Fort Mellon), and the Seminoles were numerous and stealthy in the wilds of Orange County.

Reeves was assigned to keep guard that night. His weary eyes surveyed the landscape, as the others slept at their campsite between lakes Eola and Lawsona. Something caught his eye! Did that tree just move? In a flash, he realized that it was an ambush. The Seminoles had disguised themselves behind logs. Reeves fired his gun to wake the others, but just then a volley of arrows downed the sentinel.

His fellow soldiers sprung to attention and grabbed their guns. They pursued the Seminoles through the forest, killing several of them. The natives retreated into Hughey Bay, a wetlands west of Lake Lucerne (now the intersection of I-4 and the East-West Expressway), and disappeared into the swamp.

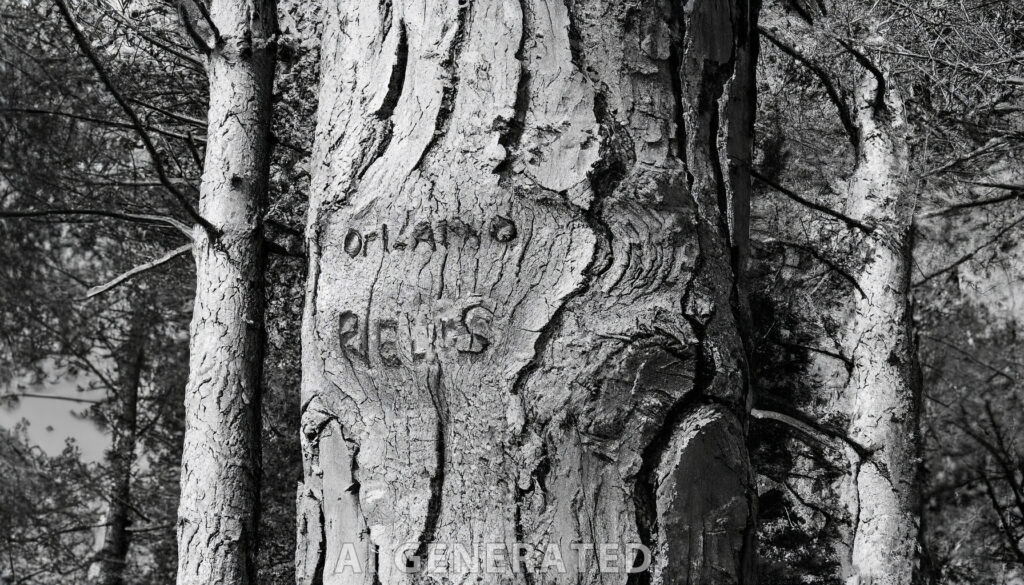

When they returned to the camp, Orlando was dead. The soldiers were thankful, at least, that he was not scalped. They dug him a shallow grave and laid him tenderly under a large tree on a knoll overlooking a lake. They carved his name into the trunk as a memorial, so that all that passed or camped here would honor the bravery of their fallen hero.

This legend became so romanticized that Reeves was commemorated with a stone monument, placed at Lake Eola Park in 1939 by students at Cherokee Junior High. This story “won out” (as Gore said in 1951) as the accepted tradition of most locals.

Although the tale of soldier Orlando had been prevalent for at least 50 years prior, Kena Fries solidified the details in her 1938 book, Orlando in the long, long ago and now. Kena is the daughter of Otto Fries, who came to Orange County in 1871. He was a prominent citizen and mapmaker, surveying every square mile of the county. Kena dedicated multiple pages of the book to the both the details of the battle and recollections of Orlando’s tree–including her father’s tears when it was chopped down by developers.

Fries tells: “In 1857…the question of a name came up, several names being proposed. The old post office had been Jernigan, the little settlement [was] frequently spoken of as Fort Gatlin. It was then during a heated discussion that Judge Speer an ardent admirer of Shakespeare arose and said; ‘The place is often spoken of as Orlando’s grave, drop the last word and let the new county seat be called ORLANDO.’ It was unanimously adopted.”

Otto Fries was not present for that meeting, but knew the original pioneers who were there. In her report, Kena reveals another important detail, as an eye-witness of the tree: the carving read “Orlando Re–s.” Most of it was still clearly legible, but the middle of the last name was not. The missing letters were presumed to be “eve,” and the spot became known as Orlando’s Grave or by other accounts Orlando’s Place, Orlando’s Hill or Camp Orlando.

One problem: muster rolls show no Orlando Reeves/Reed/Jennings or similar names ever serving in the Seminole Wars. Further, military records report no soldier deaths in what is now Orange County.

This fact was discovered by 1940 and Kena Fries even addressed it. Her defense was that Reeves was indeed a real soldier, despite his absense. She suggested there were many off-the-books militia members that served, and Reeves was not actually enlisted. He was “just a cowboy” volunteer.

Theory 3: Orlando Savage Rees

In the 1950s, a number of descendents of Orlando Savage Rees (1796-1852) came forward with a family legend of their own. The city, they said, was named for their great grandfather. Unlike the mythical soldier with a similar name, there is a large volume of documentation of his presence in Florida during the 1830s.

Rees served in the Army and attained the rank of Colonel in 1819. By 1830 he was a wealthy plantation owner, living in South Carolina. With the new territory of Florida opening up, he invested in a large endeavor at Spring Garden in Volusia County. He had a ranch there with a large number of cattle, grew crops, ran a mill, and held a large number of slaves.

During the Second Seminole War, in 1836, the Seminole warriors attacked the Rees plantation and were joined in revolt by the enslaved. Henry Woodruff, the foreman, was killed in the fighting. They burned the mill and other buildings. The Seminoles occupied his land for two years, until Major Joseph Woodruff (nephew of the slain man) led a militia force against them and forced the Seminoles to flee. Rees’ former slaves joined the natives, taking the cattle along with them.

Rees never recovered either his cattle or slaves and received no compensation from the government for his losses. He wrote letters to Washington about this and actively opposed any treaty with the Seminoles that did not reimburse him. His requests were ignored.

The Seminoles retreated south of the St. Johns River, into the swamps around Lake Jessup, Orlando, and beyond. Orlando Savage Rees led expeditions to recover his losses; however, he was unsuccessful in these attempts. It is suggested that the name carved into that tree was not “Orlando Reeves,” and it was not a grave. Instead, it was a marker carved into a pine tree by Orlando Savage Rees, as they camped by the spring hunting the Seminoles and seeking to recover his slaves and cattle.

Rees died in 1852. He is buried in Stateburg, South Carolina.

Other Legends

There have been many other theories put forward over the years lacking any citations or details. I won’t repeat those, but here are some others with some level of crediblity.

- A book published in 1914 called Tampa Blue Book and History of Pioneers says that Colonel William Harney Kendrick (1822-1901) gave Orlando its name. Kendrick was one of the first white men born in Florida and was called “the original Florida cracker.” He was beloved around the state and known as perhaps the greatest cowboy story teller.

- H. E. Browne wrote a letter to the editor in 1933 saying that he had been told by old-timers the man was actually James Orlando, who had been knocked off of his horse by a limb and died along the trail.

- Judge Speer was caring for a critically ill man, named Orlando, who recovered. They struck up a staunch frendship and he named the town in his honor. A similar story says he was Speer’s employee.

- Local historian Richard Cronin opines that Isaphoenia Speer named it for an Orlando Jones, that was a distant ancestor with the “Orlando” name reccuring a few times in ther lineage.

- Aaron Jernigan’s daughter, Martha Jernigan Tyler (1839-1926), claimed that it was Worthington who named it. She said he referred to his home and trading post as “Orlando” by 1854.

Finding Truth from Legends

Let’s start with what we know with relative certainty. These are the facts that seem consistently corroborated from first or second-hand witnesses.

- Judge Speer suggested the name “Orlando” at a town meeting, as names were being debated. It drew a fast consensus against the other options proposed.

- Judge Speer, like many others at the time, was a big fan of Shakespeare. It was taught prominently in schools and the stories were well known to most.

- The area south of Lake Eola was a popular camping spot between 1835 and 1856, along the Fort Mellon/Fort Gatlin Road, near a spring, pine tree stand, and small hill.

- There was a large tree with “Orlando” carved into it in the vicinity of the camp, which many early settlers treated as a landmark and had a strong affinity for it.

Where was the “Orlando” tree?

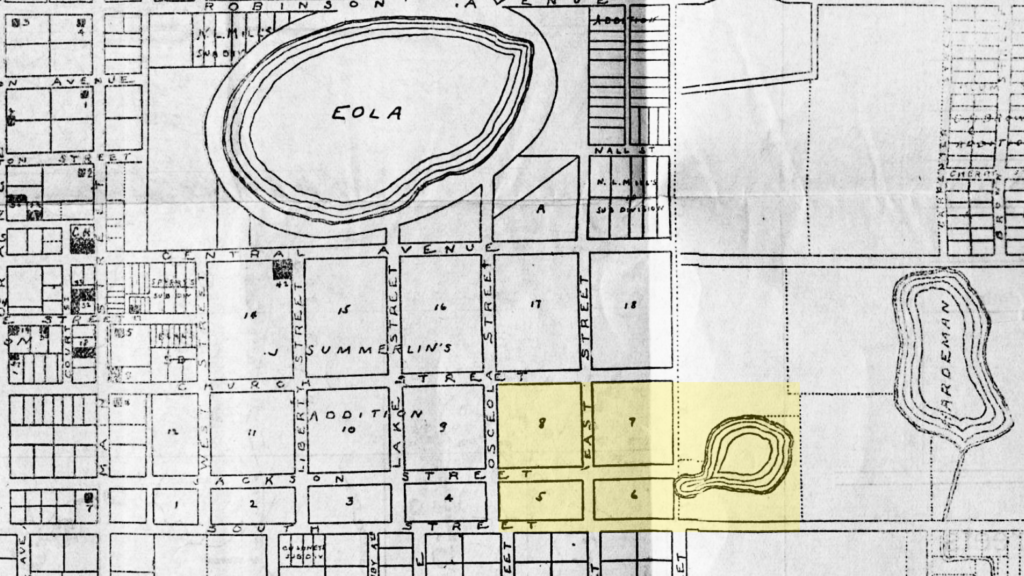

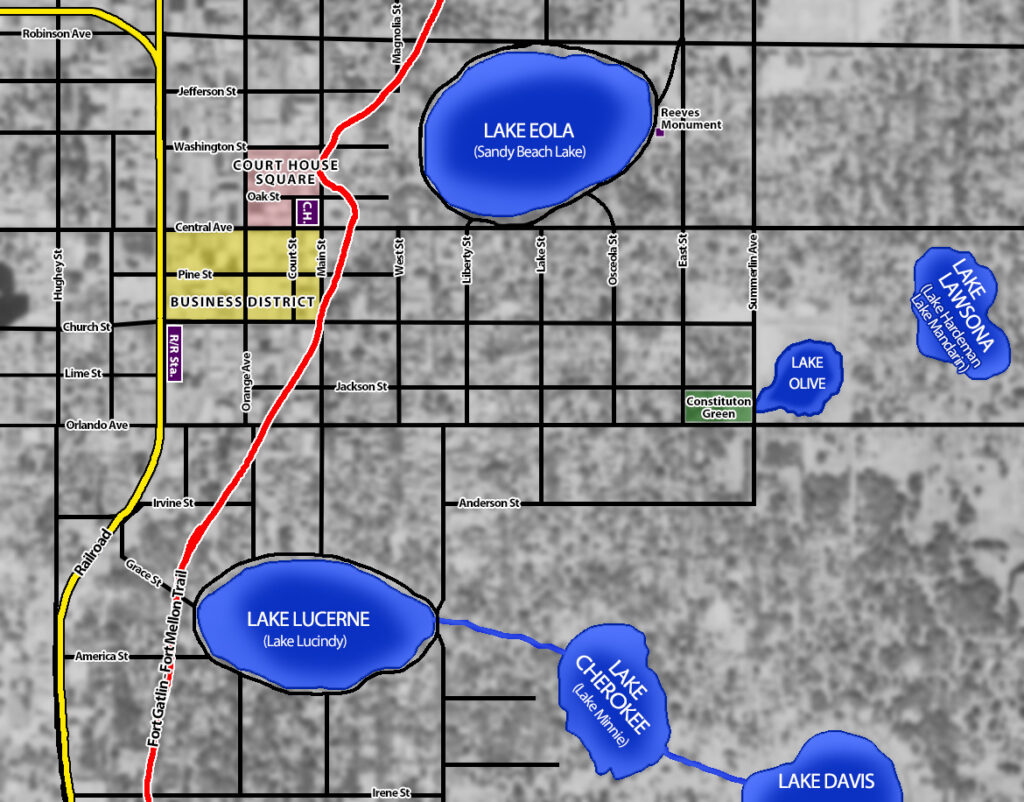

I feel confident to suggest that the original tree was located at (or near) Constitution Green, a small city park bordered by South Street, Jackson Street, Eola Drive, and Summerlin Avenue.

Harry Bumby, who arrved in 1873, identfied the exact spot of the camp to Rotary Club members in 1935. He visited it often as a young man and pinpointed the intersection of Jackson and Eola. Bumby said that he used to drink from a spring there before it was buried under the sidewalk.

William Russell O’Neal arrived in Orlando in 1886. The lawyer was personally associated with the earliest pioneers, including Aaron Jernigan, Jacob Summerlin, James Hughey, Judge Speer, and others. In a 1939 newspaper memoir, he identified the spot as Summerlin and South–just the other end of Constitution Green park from Bumby’s account. Mrs. L. D. Aulls and several other pioneer accounts from the 1920s to the 1940s give similar testament to this same location.

The 1915 Street Map of Orlando may give confirmation. It shows (now nearly round) Lake Olive with a cove running literally into Summerlin Avenue. This looks like it could be the spring that Bumby was referring to, before it was covered by pavement.

Editorials in the 1930s observed how this location of Orlando’s grave had been “kept sacred” and not built on, despite development all around it. The property was owned by the Caruso family, who arrived in 1926, but they never built on the valuable lot. Why? It was not made a park until 1987, when the Caruso family leased it to the city of Orlando for $1/year. The government finally purchased it in 2015. It’s almost like the shadow of this collective memory preserved this sacred spot all these years!

There are other references that place the marker in different locations. Some are vague such as near Lake Minnie (Cherokee), southwest of Lake Lawsona, or near Hughey Bay. Some later accounts place it on the south shore of Lake Eola, but that bank would have been swampy. It’s believed this may have been a secondary location of the memorial carving after the original was cut down.

One more thing that I discovered, that confirmed the Bumby-O’Neal account for me was an 1884 map of Orlando. It shows that South Street was then referred to as Orlando Avenue. Of course, that could be simply named for the town but it seems to be an odd location if so.

Roads are often our best modern indicators of old locations. When named after localities, they are almost always for directional purposes. However, this road bypassed the central business district (at that time) by several blocks. But, it leads perfectly to the location of the camp, spring, and carved tree.

Why would “As You Like It” inspire Speer?

Let’s assume for a moment there is a Shakespeare connection in the naming of Orlando. Why would Judge Speer specifically recall this play? I don’t think it was because it was one of his favorites.

The play is set in a beautiful, lush forest called Arden. It is densely covered with large trees and vegetation, not unlike Central Florida at that time. A key plot point is that Orlando goes around the forest carving his words of love for Rosalind into the trees.

With this in mind, the parallel is pretty strong. There was a well-known landmark tree with the name “Orlando” carved into its trunk nearby. For a society that was much more well-versed in Shakespearean lyric than we are now, the connection would make obvious poetic sense in 1857.

How Orlando REALLY Got Its Name

After my thorough research of every account I could track down, here is my final theory. It’s not Orlando Reeves or Shakespeare. It’s actually a little of both.

There was no Orlando Reeves, the soldier. The name stems from Colonel Orlando Savage Rees. On the hunt for the Seminoles that attacked his plantation, he traveled the road to Fort Gatlin. He and his companions camped at the spring, near Lake Olive. Rees carved his name into a large pine nearby.

This became a landmark, and pioneer travelers began to refer to it as Camp Orlando. The identity of the etching’s author was gradually forgotten. As parts of the etching faded to read coarsely “Orlando Re–s,” imaginations around the campfire began to take over.

Cowboys are known for weaving ellaborate and exagerated tales. The story veered further from the original with each retelling, like a Florida cracker telephone game. Possibly, famous cowboy storyteller Colonel William Harney Kendrick crystalized its details and popularlized it throughout the state.

With the popular landmark tree, it was an easy leap for folks well-educated in Shakespeare to imagine the literary Orlando having tagged it with his name and poetry to his love, Rosalind. Judge Speer drew the reference almost immediately when he arrived in 1854. It was both romantic and comical.

When Worthington built small log cabin and trading post along the trail, it was natural to reference the nearby waymarker. So when this spot was thrust from obscurity to county seat in 1856, it wasn’t that Speer invented the name; he just suggested an already familiar reference, which was easily embraced.

References

Books:

- The Blue Book and History of Pioneers, Tampa, Fla. (Pauline Browne-Hazen, 1914)

- Early settlers of Orange County, Florida (C. E. Howard, 1915)

- Grant’s Tourist Guide of Orlando Florida (1919)

- History of Orange County, Florida: Narrative and biographical (William Fremont Blackman, 1927)

- Orlando in the long, long ago (Kena Fries, 1938)

- From Florida sand to “The City Beautiful”: a historical record of Orlando, Florida (E. H. Gore, 1951)

- Orlando, A Century Plus (1976)

- Orlando: A centennial history (Eve Bacon, 1975)

Newspapers – Small subset of the newspaper articles in my research

- March 29, 1884 – Kendrick is original Florida Cracker

- November 6, 1884 – Orlando Jennings and Shakespeare

- November 27, 1884 – Town owes its name to Speer, Orlando Jennings

- November 3, 1893 – Death of Judge Speer

- November 29, 1901 – Captain Kendrick death

- November 19, 1918 – Martha Tyler said Worthington named town

- February 11, 1919 – Naming of Rosalind Avenue

- May 28, 1922

- May 3, 1924 – Story telling of Bill Kendrick

- December 30, 1925

- December 4, 1927

- December 15, 1929

- December 16, 1930 – Orlando Reeves leader of troops, arrow to heart, burned

- December 30, 1925 – Camp Orlando

- August 1, 1926 – Mr. Simmons was with Reeves, place called Orlando Hill

- May 17, 1927 – Five theories

- December 4, 1927

- December 15, 1929 – Story of Orlando Reeves

- May 11, 1931 – Orlando Reeves “settled” Orlando

- August 10, 1933 – Memorial to Reeves suggested

- August 11, 1933 – James Orlando mentioned

- June 13, 1935

- September 25, 1935 – Bumby pin points location (first page, second page)

- September 27, 1935 – “Orlando Reed” by Harry Bumby, spot still kept sacred

- December 8, 1935 – South and Eola

- February 9, 1936

- February 20, 1938

- February 23, 1938 – Dedicate “Orlando Day”? Kena Fries

- June 19, 1938 – Cherokee JH students place marker

- August 12, 1938

- December 12, 1938

- January 1, 1939

- January 14, 1939 – Marker installed on Lake Eola

- March 6, 1942 – Kena Fries comments

- April 10, 1942 – Pioneer says story is not real

- November 8, 1954 – First mention of Orlando Savage Rees, from his relatives

- March 29, 1998 – Caruso family of citrus

- April 5, 1998 – Speer great grandchildren give story

- October 3, 2015 – Constitution Green purchased

Maps

- 1884 Aerial Drawing of Orlando

- 1884 business district map

- 1890 Aerial Drawing of Orlando

- 1915 Street Map of Orlando

- Original 1956 Town Square Plat Map

- 1847 Military Survey, showing Fort Mellon-Fort Gatlin trail

Other

- Orlando Memory – Orlando Public Library

- Richard Cronin blog

- Find A Grave

- Land Records – Bureau of Land Management

- Letters about slaves captured by Seminoles – Including mentions of Rees

- Orlando Savage Rees bio

- Rees family history

- Seminole War Muster Rolls

- Historic Orlando article by Orlando Memory

- Article by Steve Rajtar, Reflections magazine October 2005

- History of Orlando (Essay by Willa Vick Griffin, 1923)

This post is 779 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.