Eyesore on I-4: Origin of the Majesty Building

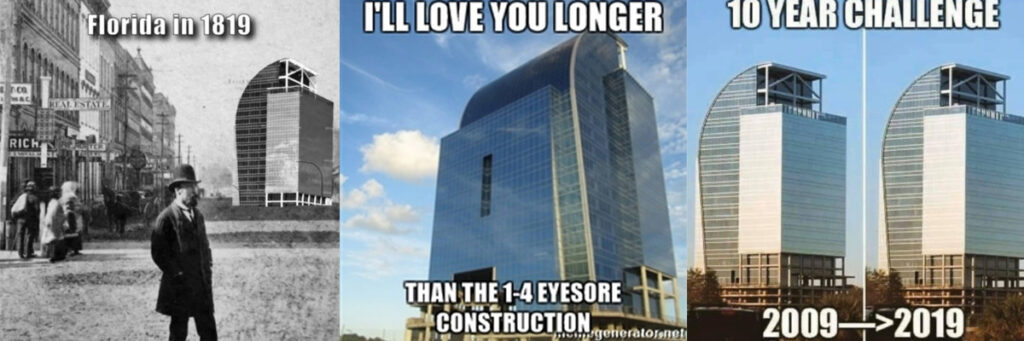

It started as a building; it became a meme. Central Floridians never get tired of a good “Eyesore on I-4” joke. The never-ending construction project started in 2001 and (as of 2024) shows no signs of being completed… like ever.

But before we talk about the present, let’s rewind the tape.

Claud and Freeda Bowers

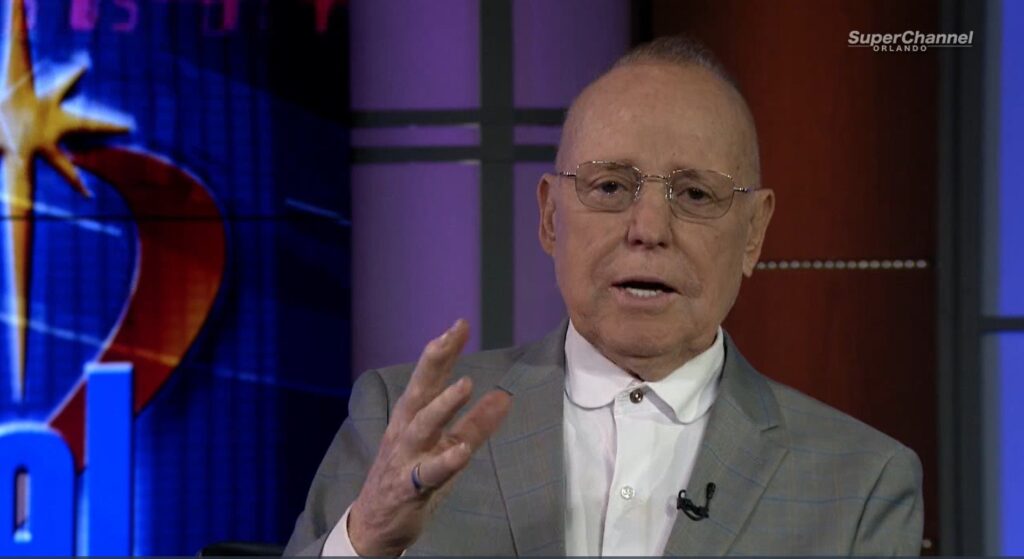

Claud Bowers is the man behind the Majesty Building. He was born in 1944 and raised in Bonifay, Florida. It is the county seat of Holmes County, an exit off the lonely stretch of I-10 halfway between Pensacola and Tallahassee. It has two traffic lights. The closest “big city” is Dothan; it is culturally closer to Alabama than Florida.

Bonifay has mostly stayed the same since Claud was a kid. The population was 2,252 in 1950 and still only 2,756 in the 2020 Census. It is your stereotypical rural Panhandle town: predominately white and poor. Its median household income of $32,500 is staggeringly low compared to the $67,917 for Florida overall.

Religion dominates the social life of Bonifay. Though it is too tiny for a Publix (they have a Piggly Wiggly), its population supports 18 churches–one per 150 people. Bower’s father, Clyde, was the pastor of the Assembly of God, a fundamentalist Pentecostal denomination that split from the Church of God in 1917.

Freeda McWaters was born in 1946 and raised on a farm in the tiny village of Bethlehem, ten miles north of Bonifay. She graduated in 1964 as a salutatorian at Bethlehem High School. Four days later, Freeda and Claud were married. She was 17; he was 20.

The couple lived in Tallahassee for a few years. The Bowers moved to Leesburg in 1969 with their two children, Angela and newborn Victor.

Launching the Station

Claud worked for ten years at the Florida Telephone Company before starting a telecommunications consulting business in 1974. It was an age where home electronics were increasingly approachable, and Bowers was a wiz at tinkering with audio, video, and radio equipment.

Channel 35 (WSWB), Orlando’s first independent television station, went on the air in 1974. It showed children’s programming, family favorites like Green Acres and Mister Ed, and the 700 Club–a popular Christian talk show hosted by Pat Robertson. The broadcaster went under in 1976, but Bowers was intrigued.

“I felt people needed it here,” he told the Sentinel. “I was so impressed with what I had seen on Channel 35… I knew I had to get into it and not just part-time.”

When Claud told Freeda about the idea, she was nervous. Throw out their financial stability for this crazy idea? After time and prayer, she saw his conviction was not fading. She agreed and was all in to help achieve his vision.

Claud sold the communications consulting business in 1977 and bought television production equipment with the proceeds. With no experience in either television or ministry, he rented out the west end of a former restaurant on Highway 441 in Leesburg and broadcast his first show on January 23, 1978.

He called his company ACTS (Associated Christian Television System). It began with just a few hours per night–cable only. Bowers rented time on the public-access Channel 11 on Cablevision Lake County. Cable television was in its infancy: the system only served 130 homes that year.

Claud was a deacon in the First Assembly of God in Leesburg. He networked with local churches to help raise money and leveraged those relationships for content: airing church services and bringing in pastors as co-hosts. The aspiring media mogul put on concerts and twice-annual telethons for fundraisers. At that time, the primary expenses in his $60,000/year budget were rent and equipment. All of his studio labor and on-air talent were voluntary.

By 1979, their coffers expanded. The media startup raised $114,000 that year and, despite a struggling economy, $70,000 the next. The growth was great, but Bowers was itching to expand beyond Leesburg.

Over the Air Broadcast

In 1980, Jim Sharp (a local radio station manager) announced that he had obtained a license from the FCC to construct a 500-foot television antenna between Leesburg and Tavares. He intended to launch WIYE Channel 55 as the first broadcast station in Lake County. Sharp promised the signal would reach from Altamonte Springs to Ocala, about 100,000 homes. He would broadcast popular programs, including reruns, sports, and first-run movies.

Bowers envied the new station in his own backyard. He was dying to reach a broader audience than the public-access cable channel allowed. He filed for an FCC license to operate a series of low-powered repeater towers spanning Central Florida. However, the federal agency denied the request since low-powered licenses were only intended for rural areas without another option. With WIYE already granted a full-powered license, Lake County no longer qualified.

The on-air debut of Sharp’s station was initially pegged for Christmas 1980 but continually slipped due to a litany of technical glitches and low funds. It finally launched with regular broadcasts in March 1982; however, the content was lackluster, and they actively discouraged anyone from watching.

“We don’t want people to look for us,” Sharp said. “We’re still testing… Our programming is not what I’d like yet. We’re just filling holes… give us another week or so, and we will be ready to go.”

That week came and went; however, Sharp’s station never did get all the kinks worked out. Bowers astutely recognized the opportunity. Bailing out Sharp’s sinking ship would be far cheaper than the $4-5 million to build a full-wattage broadcast tower himself.

By the summer of 1982, Bowers had his wish. Under his control, WIYE aired a full schedule of Christian evangelical, right-wing political content, home shopping, kid’s shows, and financial news from 7AM to midnight, seven days a week. Its antenna in Bassville could reach homes between Belleview and Winter Garden.

Unlike most other television stations, they sold few commercial slots. Instead, their budget came mostly from viewers’ donations (often $10/month) and selling air time to other content creators (charging $175 per half hour). The station aired several live shows daily, including a Bowers-hosted answer to the 700 Club called Boulevard 900, named after the address of their Leesburg studio.

The television landscape evolved quickly in the 1980s. Just as Bowers finally had his over-the-air station, more and more homes were switching to cable television. However, this wasn’t a bad thing for ACTS. On the contrary, the FCC implemented the “must carry” rule that required cable systems to include any television stations broadcast within 35 miles. Orlando and Ocala were barely within that range, but that “barely” was enough to put WIYE on the channel roster across the Orlando Metro.

SuperChannel 55

Bowers launched a massive fundraising campaign in 1984 called “Miracle 84.” His goal was to raise $1 million to become the most powerful station in Florida. In 1986, they realized that goal when they switched to a 1,749-foot tower in Orange City (the tallest in Florida) with a signal strength of 5 million watts, the highest allowed by the FCC.

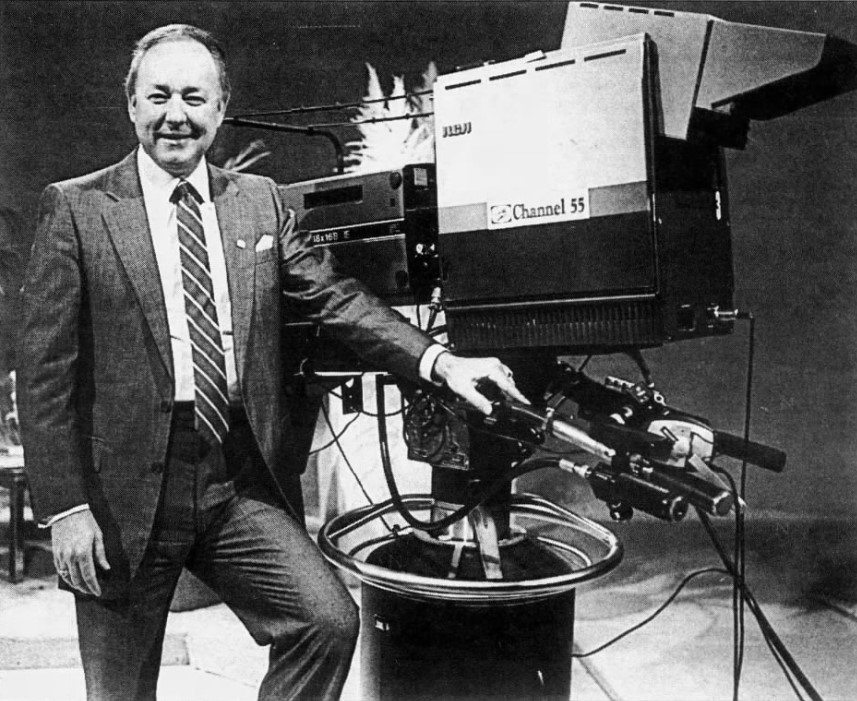

The station rebranded from “Family 55” to “SuperChannel 55” on February 18, 1986. WIYE reported their reach as two million people from Gainesville to Lakeland and from the Gulf to the Atlantic, boosting their reach from 5 to 13 counties. They relocated their studio and headquarters to Orlando.

“If you have faith and imagination, there are a lot of things you can do.”

Claud Bowers

“I never would have thought we would have grown so fast and gone so far,” Bowers said. “We’ve really learned, though, that if you have faith and imagination, there are a lot of things you can do.”

In 1987, SuperChannel brought in over $2.2 million in revenue ($6M in 2024, adjusted for inflation), with 60% of that coming from viewer pledges. The other 40% of the revenue came from selling time slots, mainly to other conservative Christian groups. In addition to its regular shows and telethons, SuperChannel aired content from preachers like Jim and Tammy Bakker, Benny Hinn, Oral Roberts, Pat Robertson, Jimmy Swaggart, and Jerry Falwell.

However, that year, the Supreme Court shot down the “must carry” rule of the FCC. Several Orlando area cable systems decided to drop SuperChannel, including Cablevision (the largest). The provider cited that Christian station Channel 52, WTGL out of Cocoa, already filled that need. At that time, they only had the bandwidth for a dozen channels on basic cable. Bowers engaged viewers and congressmen to write letters to Cablevision, but the effort failed.

Undeterred, Bowers pushed the next chapter of expansion in 1988. First, he changed the station’s call letters from WIYE to WACX, keying off his Associated Christian Television System brand. He really wanted WACT, but it was already taken by a station in Atlanta.

Next, he dusted off his earlier playbook of creating a network of low-powered repeaters throughout the state. Instead of again applying for an FCC license, he purchased existing stations. Bowers acquired three floundering channels in Tallahassee, Gainesville, and Jacksonville to simulcast his content on their airwaves.

Charges of Racism

“Don’t throw up Christian love at me. This is business.”

WACX Sales Manager

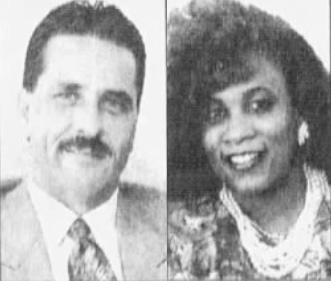

WACX ran into controversy in 1991 when it refused to air a commercial for a Daytona Beach church with an interracial couple as pastors. Reverends Kimberly and Daniel Mundell sought to spend $5,000 for five-minute commercials on WACX for their engagement at Lighthouse for Christ Church. However, WACX sales manager Clairece Kibler rebuffed them, telling them she feared the ad might offend its 82% white audience. Kibler offered to allow them to run if they only featured Daniel (who is white) and if he didn’t mention that his wife was black. The couple refused the “compromise.”

“We don’t want to offend the little mommas sending us $10, $15, $20 checks every month,” Kibler told the couple and Lighthouse founder Reverend Ron Fussell. After multiple appeals to allow them to air, they were again turned away. “Either do it this way or don’t do it… Don’t throw up Christian love at me. This is business.”

The station denied the accusations and insisted the commercials were rejected because they failed to supply credit references.

While it does nothing to excuse the discrimination they were shown, don’t feel too bad for the Mundells. Their ministry would make them multi-millionaires off the backs of predominantly low-income black audiences. The couple split in 2008 after living lavishly off of false claims made to their donors: mission trips they didn’t take, churches they didn’t build, and that God would repay their generosity with interest. They filed for bankruptcy after churches finally stopped inviting them back for their hollow “abundant living” message.

Tax Exempt Status Challenged

The Bowers were also doing quite well for themselves. So well, in fact, that in 1995, the government of Lake County revoked their non-profit status. County tax officials examined the company’s expenditures and determined the amount of money paid to the Bowers did not align with its definition of a not-for-profit organization.

Between the salaries and expense accounts assigned to Claud and Freeda, they took home $215K in 1994. This equates to $452K in 2024 dollars, adjusted for inflation. The Bowers challenged the ruling, but county officials affirmed the decision to revoke the status. This judgment only meant WACX had to pay property taxes on its broadcast tower. It had already moved its studios and offices to Orange County, which did not challenge its tax-free standing.

Dreaming Heavenward

In the mid-nineties, Bill Clinton’s economy was booming, and the fundamentalist faithful felt generous. Christian television hit its stride again, mostly recovered from the controversy around the ministry of fraudster and sexual abuser televangelist Jim Bakker.

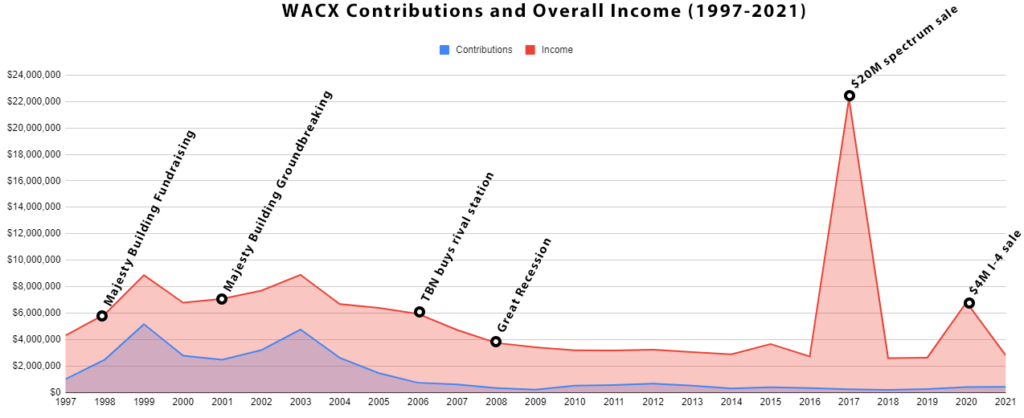

Between 1993 and 1996, WACX brought in $5.3 million in contributions and over $10 Million in total revenue. Whatever you think of Claud Bowers, no one can ever say he lacked ambition. As the company’s cash reserves stacked ever higher, he looked upward for inspiration.

In 1996, SuperChannel acquired a $1.1 Million property near the under-construction Cranes Roost Park in Altamonte Springs. The 4.8-acre parcel fronted I-4 at the Central Parkway overpass, a stone’s throw away from the Altamonte Mall. At the time, Bowers said they planned to build a hotel and conference center that shared a lobby with their television studios. He expected partners in the travel industry would sign on to finance the venture.

These plans shifted several times. Early on, it was going to be two six-story towers. That morphed into a single tower of 40 stories (which would have been eight stories taller than any in downtown Orlando); however, the project was scaled down to 20 floors when it was discovered that Altamonte Springs zoning would not allow anything over 22. The hotel and convention center ideas were scrapped in favor of retail and office space (in addition to two floors for WACX offices and studios). The final design reduced it to 18 stories.

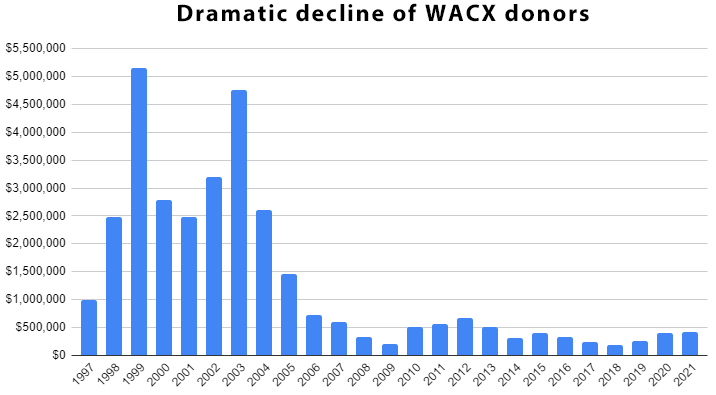

In 1997, SuperChannel made around $4 Million in revenue between donations and air sales. However, that was not enough to fund the monumental dreams of its founder. When the financial backers failed to show up, Bowers turned to his viewers to provide the capital for his endeavor. Only then did they begin to stress their “no debt” mantra.

The following year, WACX kicked its fundraising efforts into high gear. They launched a fourteen-day “Millennium Miracle Telethon” to fund the $40 Million project with pledges. Bowers asked viewers to promise $2,000 in contributions over the next two years. To his credit, he is quite the salesman, and the patrons showed up.

The nonprofit reached its pledge goal by the end of the year: between the telethon, a lavish gala, and other events. Remember that these were pledges of future donations rather than $40 Million cash in hand. However, the company received $5.2 Million in checks in 1999–far beyond any previous year (or any since).

Now having sufficient funds to get started on the project, Bowers engaged Baker Barrios Architects for $1 Million to draw up the plans for the complex. The station announced plans to begin construction in June 1999; they targeted August 2000 to complete the tower.

When that June came and went, Bowers fundraised on groundbreaking in August and opening on New Year’s Eve 2000. Blaming fears of what would happen with Y2K, they said they’d push the start to after the millennium celebration. After the lot still sat empty in early 2000, Bowers said they’d begin construction in May 2000 with a 2002 grand opening.

You see the developing theme here: delays and excuses.

Meanwhile, the Bowers gave themselves a healthy raise for all their hard work on the project. They collectively took home $500K in compensation in 1999, over $930K adjusted for inflation. However, after some raised eyebrows, the non-family board members passed a plan to limit their future salaries. Freeda and Claud’s annual compensation package was reduced and remained largely static for the next two decades.

Breaking Ground

“We chose to do it the slow way.”

Zan Partain, WACX Station Manager

They, at last, broke ground in early 2001, but only in the “dig a big hole in the ground” sense. After a long lull in progress, the foundation was laid (despite concerns after the 9-11 attacks in New York) in October. Company officials implanted 69 Bibles and a gospel songbook into the foundation during a ceremony, and the grand opening was projected for late 2003.

Construction progressed at a snail’s pace for the next three years; most days, the construction site appeared abandoned. The bare concrete skeleton towered over the interstate below. Frustrated locals cursed the sight of it, and the Majesty Building became better known by its monicker: the Eyesore on I-4.

WACX continued to fundraise heavily under the drumbeat of helping them finish the “towering pulpit to the world.” A new projected opening of May 2004 came and went, with the brutalist monument still without clothes. Finally, in December 2004, crews started to hang glass panels to shroud the nakedness of its interior.

Breaking Promises

To take complete account of the organization’s false promises and empty rationalizations would make this article overly long and repetitive. Every year, some local media publication presses Bowers for an update. He smiles for the camera, puts on the charm, and gives them a new projection. Inevitably, the fundraising goals to complete the project are just within reach. They are supposedly talking to some tenants who were itching to move in, and the grand opening will be next year. Ad infinitum.

Its completion has been a rallying cry toward donors for over two decades. Over and over, Bowers boldly claims that they only need $X Million to finish the project, so send in your check now! Sometimes, that number is $10 Million; other times, it is only $5 Million. It has floated in that range literally since the project began.

It’s like pouring into a water bucket that’s sprung a leak. Despite the contributions of its faithful, it is a goal that can never be attained, no matter their generosity.

Between 1993 and 2021, WACX took in almost $40 million in viewer contributions and around $75 million from selling airtime. In addition, they received two massive payouts from the government. In 2017, the FCC paid the station $20 Million to change to a lower channel–they sought to vacate the upper UHF band for cell phone bandwidth. It received another $4 Million in 2020 with the sale of a sliver of its property for I-4 Ultimate expansion. They received $168,200 from the COVID-era Payroll Protection Program (PPP).

The real estate and spectrum sales should have been enough to fill the remaining gap to finish construction. Only it wasn’t.

Progress did pick up. Electricity was installed in 2018; locals collectively gasped when they saw it finally lit up at night. The parking garage was finished soon after. And yet, progress has stalled since then. On paper, over $20M was invested in construction between 2018 and 2021. But observers wonder where it went, seeing few signs of further headway.

Why can’t the City of Altamonte Springs force them to finish? WACX is fully compliant with city codes as long as there is work being done. Even if no progress is visible from the outside, the organization has done incremental bits of work each month… no matter how small. This ticks the box so that it can not be declared abandoned.

Usually, the construction expenditures total about $100,000 per month. A lot of money but a drop in the bucket for a project of this scale. Especially as construction prices have risen faster than inflation.

Trinity Broadcasting Network Pulls the Plug

The Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) is the behemoth of the Christian television industry. They feature popular content such as the 700 Club, Billy Graham, Joel Osteen, Max Lucado, and Creflo Dollar.

For decades, WACX was paid handsomely to carry TBN content. In fact, it became the flagship channel for TBN nationally. WACX was carried as “SuperChannel TBN” over satellite systems nationwide. This was a huge financial boon for the WACX, both from the additional contribution dollars from the wide exposure and from the fees paid to them by TBN.

However, in 2006, Trinity Broadcasting Network called an audible. They purchased arch-rival WTGL (Channel 52), which had been a pain in Bowers’ side since they launched in Cocoa in 1982. Around the same time, TBN purchased the former Holy Land Experience theme park and moved their studios there from downtown Orlando.

With its corporate-owned station in the Orlando market, TBN no longer needed WACX. Much of its programming and the additional exposure was pulled. WACX revenue took a big hit, with contributions dropping by $850K and overall revenue decreasing by $1.7M between 2005 and 2007.

Things only got worse during the Great Recession. Viewer donations fell by 60%, between the already-decreased 2007 levels to 2009. Overall revenue fell by another $1.3M during that time and has never recovered. Revenue has continued a downward trend between 2003 and 2021 (the last year they published financials).

The Bowers Family

The Bowers family sadly lost their matriarch in 2023. Freeda Bowers co-founded WACX, served as assistant secretary/treasurer, and was active on the airwaves for decades. She authored the successful devotional book Give Me 40 Days. Though seemingly healthy at 76 years old, she unexpectedly died due to complications from surgery. She was well-loved in the community, and many greatly mourned her passing.

Claud continues to live in the home in Longwood that he and Freeda shared since 1987, located off of Markham Woods Road and convenient to WACX headquarters. It is a stately home in a desirable neighborhood, but (perhaps contrary to expectations) it is not extravagant or a mansion. It’s a respectable upper-middle-class brick house of 3,403 square feet on a beautiful wooded lot near the Little Wekiva River. However, Claud (or his corporate entities) has purchased multiple investment properties in Lake County and possibly elsewhere.

He appears as a show host seven days a week on the channel. His thirty-minute show airs in multiple time slots daily.

His daughter, Angela Courte MacKenzie, is a WACX board member and works as a presenter and in marketing for SuperChannel and various ministries of her own. She is known for her musical talent, both vocal and keyboard. She is married to her second husband, Kenneth MacKenzie, and the couple now resides on a farm in Scotland. She still contributes to the station remotely, appearing as a guest, hosting a talk show, and an entertaining musical hour of hymns around her piano.

Victor is the Creative Director at WACX. He hosts “The Vic Show,” a quirky one-man talk show where he shares whatever is on his mind and whatever eccentric props are on his desk, along with a sound Biblical message and a pleasant perspective. Victor is also quite musical, trained as a violinist. He lives in a modest townhome in a gated community just a quarter mile from the Majesty Building.

It’s difficult to track the assets and revenue streams of the Bowers family. It is spread out over many companies (some for-profit and others non-profit), including Associated Christian Television Systems, Lord & Bowers, SuperChannel Centre, SuperChannel Enterprises, Claud Bowers Center of Learning, Majesty Learning Center, ACTS II Educational Corporation, Health-Vision, Victor Communications, Capital Jewelers, Cola Cafe, SuperChannel Enterprises, Bowers Network, Bowers Trust & Holdings, Telecommunications Consultants, Sharp Communications, SuperChannel Worship Ministries, Free Life Church Orlando, Mackenzie Consulting, The Way International Ministries, Dynamic AC Properties, and Angela Courte Ministries.

The Bowers have made millions of dollars from operating the not-for-profit station. The salaries, expense accounts, and other benefits paid by the non-profit are (somewhat) public records, but they’re only part of the picture. The station also does business with other enterprises under the Bowers’ umbrella: marketing materials, telecommunications, ministries, property rental, educational material, and nutrition supplements. In addition, several loans to the company by the family presumably pay them decent interest. The details of those transactions are unknown, but some charity watchdog registries view the lack of transparency and outsiders on the board as problematic.

There’s nothing wrong with a businessman making a profit. Capitalism is good. Claud Bowers is absolutely an American business success story. With five decades of hard work invested by the Bowers family into building up SuperChannel, they deserve to reap the rewards. However, especially in an industry already clouded by fraud and excess, the murkiness of the spiderweb of companies is not the best look for a non-profit organization.

SuperChannel’s Content

The Altamonte Springs studio typically produces two to three hours of SuperChannel’s daily lineup. Most of it is not aired during primetime. There is a good reason for that. Today, less than 10% of the station’s annual revenue comes from its viewers’ pledges. It is almost completely reliant on rented airtime from other ministries. Remember, in its early days, it earned 60% from donations–that proportion was 40% as recently as 2004.

Consequently, it has little control over the views expressed in its programming. The in-house content is mostly positive and uplifting or at least benign. However, there are some problematic hosts on the rest of its roster. Let’s touch lightly on this so we don’t dive into deep ideological waters.

As you might expect, there are the standard amped-up televangelists’ supposed healings, promises of miracles, and prophesy. There are also hours of prosperity doctrine: you struggle because you don’t tithe enough; it doesn’t matter if you can’t pay your bills; send us a hefty check anyway; God will pay it back with interest. From my perspective, wealthy pastors preying on desperate folks is deplorable. SuperChannel has some of the historically most egregious offenders, such as Benny Hinn, Jimmy Swaggert, and others.

Secondly, some shows are focused on warnings of the end times and conspiracy theories. They stoke fear and paranoia. They spout anti-Catholic rhetoric and anti-gay propaganda. One show recently linked Ronald Reagan and the Pope to ushering in the New World Order and the anti-Christ. That is just the beginning. Fundamentalist viewpoints are one thing; fringe theology, divisive rhetoric, and extremist fodder are another.

Why won’t they finish the Majesty Building?

The Majesty Building appears front and center on the SuperChannel website and its fundraising material. This physical manifestation of their commitment to spreading God’s message is a powerful motivator for their supporters. Losing that marketing leverage would be detrimental to their income stream.

The Majesty Building promised to finance their ministry’s operations as a real estate endowment. According to the plan, they could fund station operations forever without relying on Granny’s monthly pledge. However, the optimism of that ideal has far outstretched the reality of demand for the 200,000 square feet of office space.

The construction would have been finished quickly if the tenants had been there initially. The economy grew steadily from the 2002 until the 2007 recession began. And yet they stalled. Under low interest rates, the financial momentum resumed in 2012. The economy roared for eight years until the Pandemic in 2020. And yet the building sat. If demand was lacking during the booms, will it ever be there?

Commercial real estate–especially office space–is in decline. Millions of square feet already sit vacant. Many workforces have gone virtual. There just isn’t demand for an Altamonte Springs high-rise office complex. And they know it.

After a theoretical grand opening, the upkeep of the building would approach $2.5 Million per year. And that’s not even counting the property tax. In its unfinished state, they are only billed for the land value ($1M). However, they’d be billed against the building’s massive valuation once complete ($60M+). Yes, the non-profit status exempts some of it; however, most of the building would be commercial real estate, which is taxable.

SuperChannel’s dwindling income just can’t absorb these costs. There is absolutely no incentive to complete the project.

Some suggest they should sell the Majesty Building. Claud shut down that idea when the Orlando Business Journal asked him. He sees no business reason to sell and further stated that it would be unfair to the people who gave them money. So there it will continue to sit.

Sources

Note: I reached out to Victor Bowers for further background discussion but did not hear back.

Orlando Sentinel

- September 2, 1965 – Angela born

- May 22, 1973 – Working at Florida Telephone

- January 24, 1978 | February 19, 1978 – Bowers on the air

- August 17, 1980 | October 1, 1980 – Sharp and WIYE

- December 6, 1981 – Boulevard 900

- December 11, 1981 – Plans to blanket the state with small towers

- February 10, 1982 | September 22, 1982 – WTGL launch

- May 22, 1982 | January 30, 1983 – Lots of TV options in Orlando

- March 8, 1982 – WIYE broadcasting, kind of

- April 8, 1982 | April 22, 1982 – Bowers to buy WIYE

- June 8, 1982 | June 15, 1982 | June 17, 1982 – Launches Family 55 on Cablevision

- April 12, 1984 – Miracle 84 Telethon

- September 15, 1985 -Interview with Claud

- February 16, 1986 and March 8, 1986 – Rebrand as SuperChannel

- June 20, 1987

- February 22, 1988 – Dropped by cable

- August 23, 1988

- May 29, 1989 – Interview with Claud

- September 27, 1991 | September 28, 1991 – Mixed race commercial controversy

- October 17, 1991

- June 3, 1993

- December 7, 1995 – Denied tax exemption

- September 2, 1996

- April 7, 1998

- May 12, 1998

- September 16, 1998 | October 7, 1998 – Telethon starting

- December 12, 1998

- December 16, 1998

- January 23, 1999

- April 14, 1999

- October 27, 1999

- May 3, 2000

- February 11, 2001 – Moving dirt for seven months, blame trying to find a buyer for it for delay

- September 28, 2001 – Towering pulpit, foundation being laid

- October 3, 2002 – Worked stopped, “Faith at Work”

- March 13, 2003 | March 16, 2003 – Skeleton building

- December 1, 2003 – Starting construction again, adding 15th floor

- December 5, 2004 – Panes of glass finally go on

- June 22, 2005 – Top curved section is on, picture of worker walking on it

- July 6, 2006 – TBN buys WTGL

- August 13, 2006 – Work going slowly

- February 12, 2017 – a year to 18 months more

- May 29, 2018 – 18-24 months from completion

- August 23, 2019 | August 24, 2019 – Blames I-4 Construction

- March 25, 2022 – Two decades later

Orlando Business Journal

- Orlando Business Journal – September 19, 2019

- Orlando Business Journal – September 23, 2019

- Orlando Business Journal – September 25, 2019

Other Sources

- Orlando Weekly – January 11, 2022

- Freeda Bowers Obituaries: Charisma News | Legacy

- WSWB/WOFL (Channel 35, Orlando) History – Wikipedia

- Must-Carry Rules History – Free Speech Center, Middle Tennessee State University

- PTL Club and the Bakkers – Wikipedia

- UHF Channel Reassignment

- Majesty Building Wikipedia

- WACX Website | Get Paver Stone and Key to Crown Room

- Pro Publica Non Profit Explorer

- Charity Navigator

- Sunbiz

- Claud Bowers LinkedIn

- Angela Courte Mackenzie LinkedIn

- The Vic Show with Victor Bowers – Talks about the Majesty Building

- Cause IQ

- PPP Loans to Televangelists | PPP Loans

- Interview with Claud Bowers, shares his story of getting started

- Hours of watching WACX live, YouTube, and Facebook

- Many more articles and social media pages than I can list!

“Bill Clinton’s economy was booming” LOL. The economy was booming, but it had nothing to do with philanderer Bill Clinton. It was the beginning of the internet boom.

A very well researched and well written article. I’ve read several others about this building but none came anywhere near this level of background, detail, and analysis. And yet you made it a very entertaining read, top to bottom. Kudos.

Does anyone know how the administration can be contacted? Interested in having a tour of the building.

Good luck with that. I know them personally and they wouldn’t even give me a tour. I have not seen a single soul enter that building in years. They use to have a security guard but haven’t seen them for a while either, but maybe I just haven’t seen them.