The Pioneer Life and Murder of Dempsey Dubois Crews, Jr.

The well-known cowboy came to frontier Zolfo Springs as a boy and later founded the town of Crewsville. Then, his life was needlessly cut short in a dispute over hogs.

The Wild Wild West of the “Big 90”

The Peace River Valley of the early 1800s was an inhospitable and largely unexplored wilderness. There were no white settlements outside a few forts and a trading post. Skirmishes with the Indians were commonplace, and the body count on both sides was substantial.

But bit by bit, the natives were being driven off their lands and pushed further south. By 1850, the Seminoles that remained in Florida had been squeezed into the interior, mainly relegated to the unwanted muck lands of the southern part of the state.

In 1854 the federal government struck an agreement; the natives were to stay south and east of the Peace River. Settlement south of Fort Meade and west of the Peace River was opened for white settlement. A steady wave of settlers from northern Florida and southern Georgia trickled down.

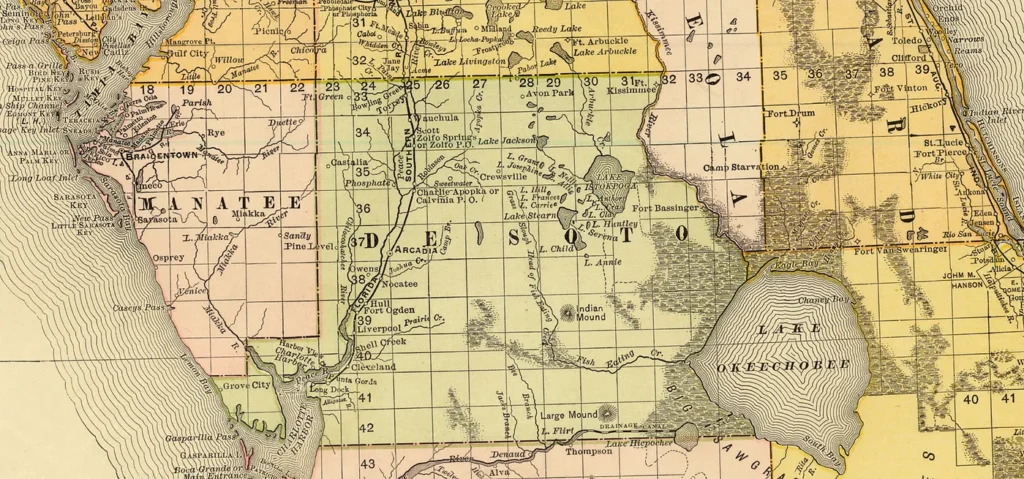

Before 1887, the massive Manatee County was bigger than some states. It included the entire region known as the 90-mile Prairie. This mostly flat and uninterrupted grazing lands stretched from the Kissimmee River to the Gulf of Mexico. Tens of thousands of wild cattle descended from ancient Spanish herds and roamed this vast grassland, pine forest, scrubs, marshes, and streams.

In 1887, the eastern half, getting sick of being ignored by the more populous coastal section, broke free to form DeSoto County. It encompassed what today is Hardee, Highlands, DeSoto, Charlotte, and Glades counties.

During the era between the Civil War and the turn of the century, the Peace River Valley was eerily reminiscent of the Wild Wild West. Cattle and hog thievery were rampant. Even the most legitimate of cattlemen felt forced to resort to hiring rustlers of their own just to get back to even from the losses they’d suffered.

Livestock was branded and re-branded until their marks were no longer recognizable. Animals would arrive to market with the ears lobbed clean off to mask their original ownership (earmarks were also used to identify to which rancher they belonged). Meat markets knew they were dealing in hot goods but eagerly accepted the discounted sale price anyway.

The legal system, where it existed, was often seen as useless. Even if the chain of custody of the stolen stock could be proven, justice wasn’t often done, and rustlers would be right back to their task in no time.

Consequently, area cowboys often took the law into their own hands. Family clans and bands of friends enforced the law the cracker way. This resulted in longstanding feuds, brawls, gunfights, bushwhacking snipers, and flat-out executions. If you imagine the county seat of Pine Level like an old western movie, with saloon doors swinging open and gunfights in the street, you’ll be pretty close to reality.

Crews/Collier Family Accepts the Challenge

The Crews family first moved to northern Florida from Georgia a year before Dempsey Crews, Jr. was born at Lake Butler in 1846. They remained near Lake City until the end of the last Seminole War in 1858. His father (also Dempsey, I’ll refer to him as “Senior”) served in the final two of those three wars, battling the remaining tribesmen who refused to be quietly removed to Oklahoma.

In 1859, Senior, his wife Piety Collier Crews, and their (at the time) nine children loaded up everything they owned into an oxcart caravan. Piety’s brother John Collier and his family joined them as they began the long trek southward toward their new home in what is now Hardee County.

The families traversed sandy trails, almost impassible bogs, and miles upon miles of utter nothingness. Behind the wagons, the men rode on horseback, driving their meager herd of cattle and a few dogs. The sweet potatoes and corn they hauled offered some sustenance on the journey; the pine forests, scrub, and marshes provided them an ample supply of wild turkeys, deer, and watering holes along the way.

After over a week on the trail, the weary settlers arrived at Fort Hartsuff. They temporarily camped with their Whidden kin folk at their homestead, just northeast of present-day Wauchula, where the Heard Bridge crosses the Peace River. Dempsey was just 12 years old at the time.

Settlement of the Fort Green and Fort Hartsuff areas had only (officially) opened up recently, but there were already a dozen or so established families. By agreement with the Seminoles, the white settlement was not to extend south or east of the Peace River. However, when did the government ever keep its promises to the natives? Answer: never.

Regardless, the Thompson family had already violated those terms by settling near Popash earlier that decade. With that in mind, the Crews and Collier families soon continued southward to become the first settlers in the vicinity of what is now Zolfo Springs.

Although some earlier maps show a pre-existing trail, legend has it Senior built the first road connecting (what would become) Zolfo with Fort Hartstuff. The abandoned military camp was south of Wauchula, close to the modern-day intersection of South Florida Avenue and Altman Road.

The family crossed the Peace River about a half mile east of the present-day Highway 17 bridge. Senior graded the shores to make a safe crossing. For years, it was known as “Crews Ford” and later “Brannon Ford,” after another relative.

Building a New Life

The family constructed a sprawling homestead south of the River. They built log homes, fences, and cow pens. Various crops were planted, including sweet potatoes and corn. A high fence enclosed their garden, keeping the chickens, wild turkeys, and other creatures out. Nearby they cultivated sugar cane and a small patch of cotton. The family raised chickens, hogs, and cattle for milk and beef.

With so much work to be done, it was beneficial to have a large family. In all, Senior would have 17 children. Dempsey Junior would eventually have 14 of his own. Not to be outdone, Uncle John Collier Sr. had a total of 18! Other branches of the family soon joined the large clan in the new homeland.

Despite having that many hands to help out with household chores and farming duties, the Crews family had additional assistance: slaves. Senior brought eight slaves with him to Zolfo — a 35-year-old woman named Hagar and her seven children. The Whidden family had two of their own.

However, these pioneer families of the Peace River Valley were very much in the working class. There were no wealthy plantations in old eastern Manatee County. Out on the rugged frontier, everyone worked hard and played a role. The few families in the region that did own slaves had only a handful, mainly females, as household help.

The Damned War

In 1861, little more than one year after the Crews family felled its first tree, the Civil War erupted, and Florida seceded from the Union. Unlike those in neighboring communities like Bradenton, most of the cattlemen in (what is now) Hardee and DeSoto counties did not support the Confederacy. They wanted nothing to do with the war.

They hoped to lay low in their prairies and hammocks and avoid all involvement. Many filed for exemption when mandatory Confederate conscription and other Rebel service were required. The men simply wanted to live unmolested country life, carry out their business, and care for their families.

Eventually, these pioneers could no longer avoid the escalating turmoil that severely crippled the cattle industry. In December 1863, Union General Daniel Woodbury seized Fort Myers and set up a stronghold there. In short order, a host of Hardee County settlers (including those owning slaves themselves) decided to sign on with the Union forces at Fort Myers.

Dempsey, his brother William Madison Crews, and their Collier and Whidden cousins were enlisted in Company B, Second Florida Cavalry for the United States Army.

In fact — I’m sure many will be shocked to find out — a large majority of the 1860s population of today’s Hardee County were Union loyalists. Yes, even after the war, most remained Republicans (some very actively so), the party of Lincoln, abolitionists, and Reconstruction.

Crewsville Breathes Its First Breaths

The War Between the States ended in 1865. Cow hunters returned to minding their herds across the vast open range, and the port at Punta Rassa was reopened for cattle shipments.

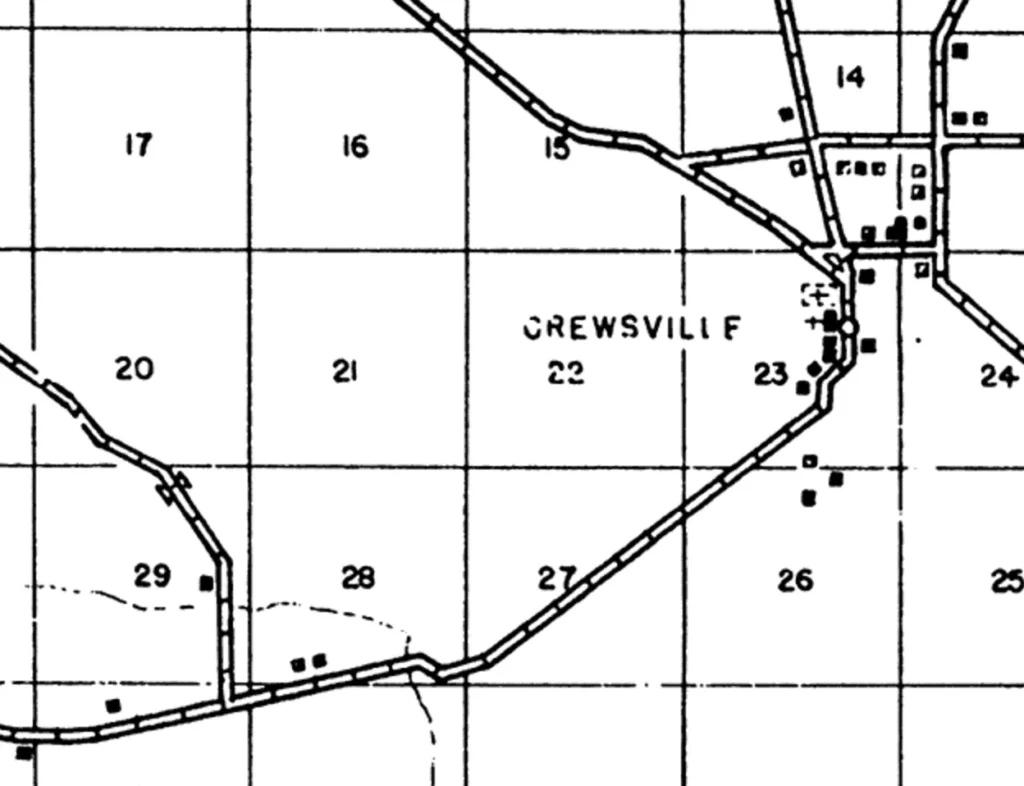

In 1867, Dempsey decided to strike out on his own. Crews, along with his uncle John Collier Sr. and father-in-law Enoch Collins Jr., established the settlement of Crewsville about 14 miles southeast of Zolfo Springs.

Before the railroad came through in 1886, Crewsville was one of the most prominent settlements in the area. Before there was any semblance of a town at Wauchula, Zolfo Springs, or Bowling Green, the tiny outposts of Fort Green, Popash, and Crewsville were about it.

At its peak, Crewsville boasted three stores, a post office, a Baptist church, a graveyard, and many homes. Dempsey owned the general store in town and served as postmaster for a time.

The meager store inventory first came by boat down the Peace River; later, it came by train. Then, the wagon brought it down the sandy path from Zolfo to stock the shelves with the bare essentials and not much more.

Settlers occasionally traveled to town to trade and stock up on supplies before returning to their frontier homesteads. The Crews general store was a community meeting place by default.

Despite its early promise, the Florida Southern Railway bypassed the town. And, although it would take decades to fully fade, that was the beginning of the end for Crewsville as a center of commerce. The town’s post office was retired in 1916. Today, only the Bethel Baptist Church and a road bearing its name betray the town ever existed.

It All Started Over Some Hogs

Dempsey’s son, Enoch “Ed” Crews, opened the family’s general store at 6AM on June 10, 1895. After about an hour and a half, a local man named John Lucas stopped by to trade.

John Collier, Jr. and good friend Fritz H. Williams entered around 8:00. The men were stopping by to make preparations to leave on a cow hunt. Minutes later, Dempsey walked in, a pistol and a shotgun holstered around his waist, with plans to accompany John and Fritz on the outing.

Dempsey was five-foot-five with a light complexion, grey eyes, and light hair. Despite his diminutive stature, he hadn’t the slightest bit of timid in him. He was an outspoken leader in the community, and people respected him greatly. The founder was not fond of violence but not afraid of it either.

Lucas was not happy to see him. He immediately threw ire upon the store owner, opining loudly that Dempsey’s cousin Charlie Crews was responsible for some missing hogs. Dempsey fired some words back in protest, possibly denying the accusations.

According to an eyewitness account, Crews insisted, “I do not want to have any difficulties with any of you. We are all friends!”

In an attempt to interrupt the confrontation, Collier walked to the door, saying, “We had better start.” Dempsey agreed. He followed Collier as the men left the store and headed to their horses. Just as the men had mounted, Lucas huffed over to the head of Dempsey’s horse.

“I have had just about as much of this as I can stand,” Lucas protested. “Any man that would take up for a hog thief is no better than a hog thief!”

“And I have had as much as I can stand too,” Dempsey replied. “I am a white man in a free country and can say what I damn please!”

Immediately, Lucas headed over to Crews to pull him down from the horse. Dempsey drew the pistol from his belt and pointed it at Lucas, telling him he needed to back off.

At the sight of the loaded weapon, Lucas halted his progress. Then, running to his own wagon, he yelled, “By God, I’ve got something too!” He pulled out a double-barreled shotgun, cocked it, and held it to his face. It was pointing directly at Dempsey.

Hearing the commotion, Ed Crews had come outside. Seeing the gun, Collier yelled to Ed, saying, “Catch the gun!” The 23-year-old ran from the side of Lucas to intervene on his father’s behalf.

Ed grabbed the gun, and Lucas warned, “Turn it loose, Ed, or I am gonna hit you.” Lucas then punched the young man in the face and shoved him back. Ed ran over to where Collier and Fritz were still on their horses. Both were in the process of dismounting, given the escalation.

Seeing his son being struck by Lucas, Dempsey exclaimed: “Well, I’ll be — If I take that!” Lucas immediately whirled around to face Dempsey and fired the gun.

Dempsey got a shot off first, and a split second later, Lucas fired, followed in quick succession by another shot from Crews. The second shot from Dempsey struck Lucas in the leg.

“Oh Lord, I am a dead man,” cried Lucas as he stumbled off about 15 feet before falling on his face. Dempsey wasted no time rushing toward Lucas. When he was just a couple of steps away, Lucas turned over and aimed the gun again at Dempsey. The two struggled over the gun for a few seconds. With Lucas still on the ground, Crews quickly gained control and then shoved the gun back at Lucas.

Crews turned and walked away, rounding the corner of the store to head back to his horse. Collier followed initially but then decided to check on Lucas to see if he was dying or wounded. As he approached, Collier saw that Lucas had gotten up to his feet in pursuit.

At that moment, Dempsey had one hand on the horse’s neck and one on the saddle as he prepared to mount it. Lucas raised the gun again to his face, and John cried to his cousin, “Look out, Demps, he’s going to shoot you!”

Upon hearing the warning, Dempsey turned just in time to catch the buckshot to his face. Collier could not see the shot, but as he ran around the store, he saw his kin and cow-hunting partner lying face-down. He rushed over and turned the 49-year-old onto his back.

“Have I killed him?” asked Lucas. “You have killed him!” Collier replied in anguish. As the three other men tended to Dempsey, Lucas fled.

The Fate of John Lucas

The story hit the wire, and the incident caught national attention. Lucas was soon captured and brought to Arcadia to stand trial. Dempsey, being a well-respected citizen with a large extended family, the sheriff feared a mob might extract Lucas from the jail and enforce their own expedient justice. He was kept highly guarded in his cell to prevent a lynching.

Lucas’ injuries were not serious, receiving a spattering of fine bird shot to the back of the hip. While held in the county jail, his wife was permitted to serve as his nurse and attended to his wounds.

On November 2, 1895, the circuit court trial began with John Lucas charged with the murder of Dempsey Crews, Jr. The state called witnesses, including J E Knight, Fritz H Williams, H Williams, John Collier Jr., T B Cason, L Prescott, Charles Mercer, Nellie Collins, Ed Crews, and William A Williams.

Despite the evidence and witness testimonies, the jury returned with a quick “justifiable homicide” verdict. Though the facts of the case were corroborated by multiple accounts, the frontier culture had become desensitized to such acts of violence and agitated with many hog and cattle thieves. Perhaps they thought Lucas’ rage was justified, given his stolen hogs, or maybe it was because Crews had shot Lucas first?

Regardless of the jury’s rationale, Lucas was freed. He moved to the southern part of the county near Fort Thompson, which was on the Caloosahatchee River close to LaBelle.

A year later, fugitive Jim North, having killed Bud Sauls, had been on the loose for about two years. A reward was offered for his capture — dead or alive. The cash was too tempting for Lucas to ignore.

With the help of North’s “friend” Jim Daniels, the duo lured North on a “hog hunt.” Lucas hid in the grass beside the road, and when North approached, he shot him dead at point-blank range. Hauling his body to Arcadia by wagon, they redeemed the reward for his capture.

In 1897, Lucas and his friend Dennis Sheridan were employed by T. E. Langford as live-in managers on his ranch six miles north of Fort Thompson. Sheridan was a former outlaw (noticing a pattern?), having killed F. Q. Crawford years before.

The two friends had been drinking when newcomer William Love arrived at the ranch to deliver a message to them. In his drunken state, Sheridan jumped up and accused Love of being a detective searching for him. He pulled out a knife and slashed Love’s left arm.

Lucas rose up to intervene. Sheridan turned and cut his friend on the left cheek, then his throat and left arm in succession. Still raging, Sheridan stabbed Lucas several times in the side until he fell to the floor and exclaimed: “You have cut my lungs out!”

John’s wife ran to his aid and received minor cuts. Sheridan fled into the bush, and his fate after that is unclear. Contemporary newspaper reports claim Lucas’ injuries were fatal, which might seem sweet justice to some. However, historian Canter Brown reports otherwise in his book Florida’s Peace River Valley.

Brown continues to say that Lucas rode near Fort Thompson on June 6, 1898, with his friend Dan Byrd. Then, from out of nowhere, a bushwhacker “emptied a load of buckshot into Byrd, dropping him instantly.” It is not known whether Byrd or Lucas was the actual target.

Lucas must have had nine lives; he floated from one bloody incident and the next. Nothing can be found of his destiny after that final incident. His name does not appear in any area Census records thereafter. Maybe he moved, or conceivably, he finally ran out of lucky breaks.

Conclusion

After the turn of the century, life on the 90-mile Prairie slowly began to take on a more civilized tone. The rampant violence and cattle thieving ended, at least on a widespread basis.

Over 150 years after their original settlement, the family trees of the Crews, Collier, Whidden, Collins, and other related lines continue thriving as prominent families in Central Florida. They are among the original founding families honored at the Cracker Trail Museum at Pioneer Park in Zolfo Springs.

This post is 3200 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.