Hicoria, Florida went up in smoke

Hicoria does not exist. At least not anymore. It doesn’t even get the courtesy of one of those green signs like many other ghost towns. The only indication of this former boom town is in the name of Hicoria Road, which stretches from US 27 to Old State Road 8, halfway between Lake Placid and Venus. But for six years, it was booming.

Funny side note about Old State Road 8: it was never State Road 8, at least not south of Lake Placid. It was Highway 26, but I digress...

Pioneer Settlement

Before 1890, there were very few non-native settlers in what is now Highlands County (then part of DeSoto County). The only tiny collections of humanity were centered around Avon Park, Venus, and Fort Basinger. The small black settlement called Niggertown Knoll had already vanished. The rest of the county was the home of free-range cattle, nomadic Seminole hunters, and raw wilderness.

James “Jimmie” Carlton visited the area around 1894. It is located on the southernmost tip of the Lake Wales Ridge, just before it dips down into the Everglades. Carlton observed the gopher tortoise burrows along this hilly section. This old pioneer trick revealed a bevy of red clay not far under the surface below the sugar sand. He knew the clay would hold moisture well and make an excellent place to cultivate crops.

The 41-year-old relocated his family to these highlands. He ran his cattle in the prairie to the west and cleared a few acres of orange groves on the ridge. The citrus thrived in the soil, and the location this far south proved freeze-resistant. This caught people’s attention, especially after the Great Freeze that same winter knocked out most of the industry further north in Florida. The region became known as the “Red Hills” district or the “Redlands.”

Despite the prime location for ranching, few settlers (outside of a second generation of Carltons) followed. Transportation was the main reason. There was no railroad nor navigable waterways to Redlands. The only access was over a sandy old military path known as Footman Trail, which went north to Hooker’s Cow Pens at Highlands Hammock and south to Venus.

Railroad and post office puts Hicoria on the map

Twenty years after the Carlton’s moved in, they got a new neighbor: the Atlantic Coast Railroad. In 1914, the line was extended from Sebring to Moore Haven. The ACL added a few pioneer flag stops along the route, and the Carltons donated some land to have a siding put in adjacent to their property.

While they surveyed the best route, famous botanist John Kunkel Small was on one of his many expeditions into the wilds of Florida. He was interested in the large population of a local hickory variant known as Hicoria Floridana. He convinced the company to name the station after the tree, and it’s been known as Hicoria ever since.

With the new ease of accessibility, Hicoria’s population swelled… well, relatively speaking, at least. It went from about three families to a dozen. Locals circulated a petition and was granted a rural post office in 1915. Charles B. Collins served as postmaster for the first two years, followed by short stints by Lizzie Carlton, Daisy M. Eures, and John Paden.

Charles H. Shackelford took over the duties on August 4, 1920, and ran mail service out of his home for the rest of its existence. His home was located a half mile off of the highway passing through Hicoria. Shackelford laid sawdust and palmettos on top of his driveway to make it passable to automobiles. Sandy trails radiated in every direction from the house. Homesteaders carved their own crude pathways to collect mail. Even a decade after it opened (1925), it served just 15 families. These pioneers were scattered among the miles of grove and forest.

Understand that the term “highway” in the previous paragraph is used loosely. It was an eight-foot wide clay path that ran from Lake Annie to Old Venus. It wasn’t until newly-formed Highlands County received money from road bonds in 1926 that it was paved with asphalt to the Glades County line.

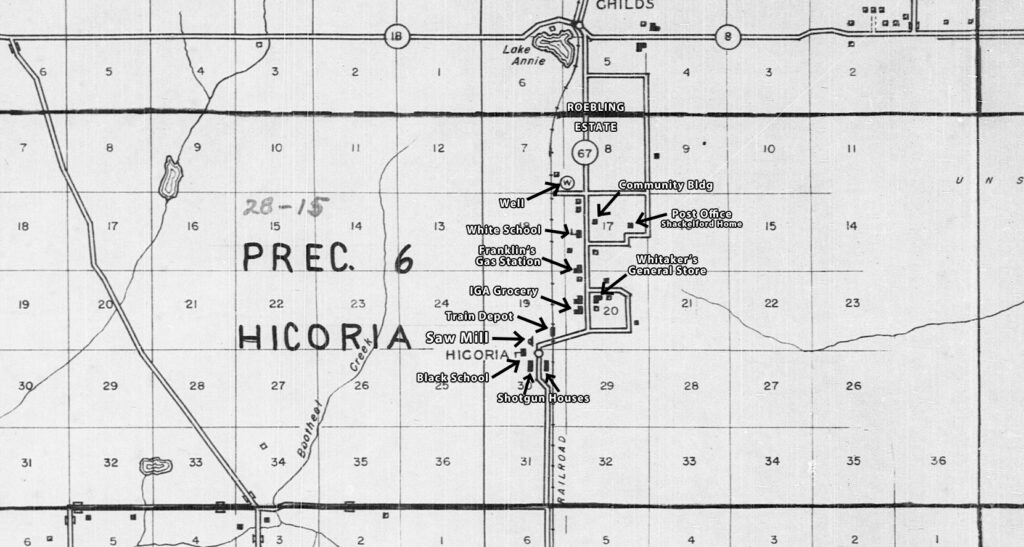

Automobiles became increasingly popular in the mid-20s, and a small number of commercial buildings began to congregate along the road. The Whitaker family opened a general store, and the Franklins operated a gas station. The closest churches were in Venus. Ceylon Carlton donated land for a schoolhouse, which was opened for the 1923 school year. E. J. Peters, George Kelsey, and Nita Sapp were some of the early teachers.

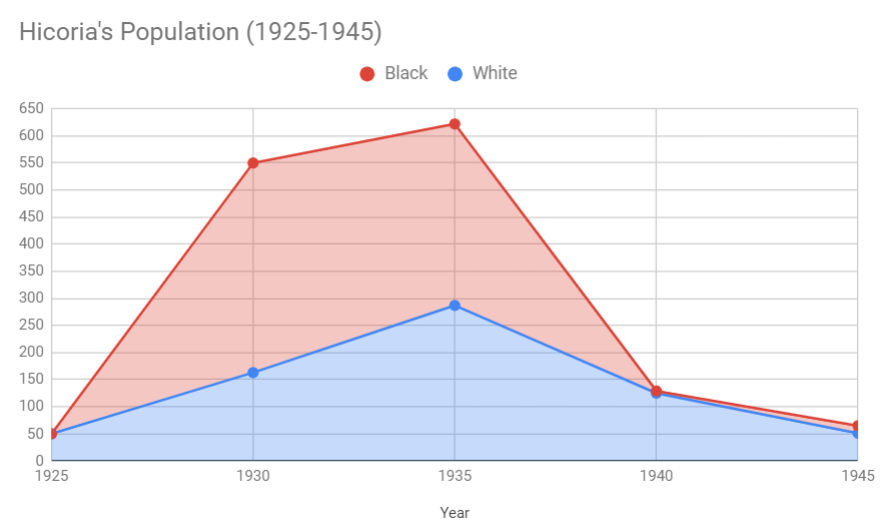

Even so, the 1925 Census reported just 50 people living in the Hicoria precinct.

Pioneer Life

Despite the remoteness, frontier families enjoyed a robust life. The forest was dense with game. The lakes, about six miles north, teemed with fish.

“There was so many quail, you could go out and fill up your hunting coat without a dog,” said Horace Shackelford. “It wasn’t nothing for us to bring home a hunting coat just as crammed as it could be with quail.”

Quail was served fried or simmered over a bed of black-eyed peas. Other favorites included deer, dove, wild hog, turkey, opossum, squirrel, and even gopher turtle. Many families had chicken coops for fresh eggs and meat. They foraged for guava, blueberries, huckleberries, bog blackberries, grapes, swamp cabbage (hearts of palm), and hickory nuts. The women were skilled at canning and making jams out of the abundance.

The Seminole Indians hunted and camped throughout the area; relations were friendly. A band of 15-20 wandered through the settlement every few months in search of game. They would help themselves to oranges and perhaps stop to trade. Bootleggers also visited the Hicoria general store, hoping to exchange their illegal whiskey for furs or other goods.

Crime was still an issue, however, especially during the Great Depression. Hamp and J. T. Anglin were part of a crime family that hit stores, homes, and banks throughout the area. Items from a burglary at the Hicoria’s railroad depot were found in the Anglin home when it was raided by Sheriff Doyle Schumacher.

Sherman Lumber Company

The news struck Hicoria like a lightning bolt; the Sherman Lumber Company was coming to town. They purchased the timber rights to thousands of acres of pine forest west of Hicoria, owned by turpentine producer Consolidated Naval Stores, the Carlton family, and others. On November 6, 1928, they broke ground on a massive sawmill near the rail depot and Highway 26 (later re-numbered 67) through the settlement.

The plant was completed quickly, opening in early 1929. Seemingly overnight, the population surged 11-fold, from 50 to 550 people. Hicoria became one of the largest towns in the county!

The veins of Hicoria pumped with life. Next to the sawmill, the company built a commissary and 42 shotgun houses for workers. The housing boom gave rise to a community building, an IGA grocery store, ball fields, and basketball courts. The black workers, who made up more than half of the town’s population, were congregated south of the mill in one or two-room shotgun houses. A colored schoolhouse was added nearby.

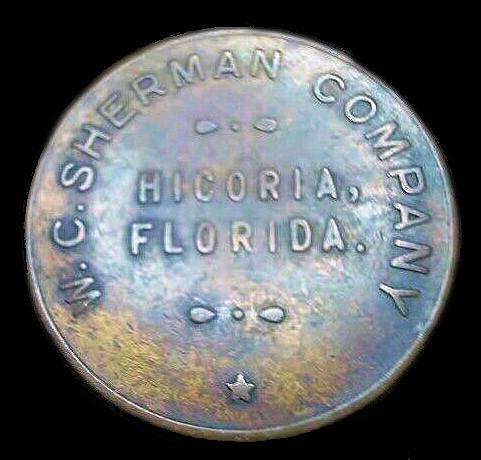

Workers were often paid in “scrip” instead of money. Though considered a shady practice, it was perfectly legal. It could only be spent at the company store, creating a circular dependence that was almost akin to slavery.

The best timber lay up to seven miles west and north of the Hicoria mill. To reach it, workers hastily laid wooden rails. Narrow-gauge train cars, called trams, ran over the tracks with a steam locomotive to haul the lumber back to the mill. As the trees were exhausted from that area, they’d either extend them further or pull up the tracks and move them to another location. The supply of good quality pine must have seemed endless.

The hand-cut lumber was dried in a kiln for a number of days before being cut into planks or siding. At its peak production, the mill churned 50,000 board feet per day.

The Roebling Estate

John Augustus Roebling II first came to Highlands County in the mid-1920s as a guest of Melville Dewey, who was invested in creating a winter retreat community at Lake Stearns–that he renamed Lake Placid after the resort town in New York. Roebling made much of his fortune as a manufacturer of steel cable. He came from a line of civil engineers, including his famous grandfather, who designed the Brooklyn Bridge.

John’s interest in the area was driven by its warm climate. His wife, Margaret Shippen Roebling, suffered from tuberculosis. Common wisdom at the time said that the Florida climate could cure the ailment.

In 1929, the Roeblings purchased a 1,050-acre tract of scrubland north of Hicoria and south of Childs. They called their sprawling estate Red Hill.

At once, they employed a large and relatively well-paid staff of caretakers and construction workers, including the estate’s foreman, Alexander Blair. The first large project was a large concrete and steel storehouse. Hurricanes wrecked much of Florida in 1926, so Blair designed the buildings to sustain even the strongest winds. It was to serve as a warehouse, workshop, and office headquarters for expansive grounds.

Unfortunately, Margaret did not live long enough to see its completion. She died on October 23, 1930, at 63 years of age. John continued to support the property as a tribute beyond her death. He completed many of the planned structures and kept a staff on site, including its own fire department.

This continued until 1941 when Roebling donated the property to independently wealthy zoologist Richard Archbold for its eternal preservation. Archbold turned the estate into a research center, now known as Archbold Biological Station. Richard purchased an adjoining 2,823 acres of land to expand its area, and he lived there for the rest of his life (1976).

Fire at the Sherman Mill

There were numerous fires at sawmills during this era. It was just the cost of doing business. Embers could often ignite outbuildings, woods, or nearby homes. There were two fires in 1932; one burned up 80,000 feet of lumber.

However, it was the blaze on June 22, 1935, that locals never forgot. The fire started when an ember from a stream engine lit a pile of dry lumber. The planing mill, ramps, and an estimated 1.8 Million feet of lumber were destroyed. The damages exceeded $60,000 ($1.4 Million adjusted for inflation). Fire departments from Sebring, Lake Placid, Arcadia, and the Roebling Estate all responded to help battle the blaze.

“It must have taken us 12 to 15 hours to get it completely under control,” said Roebling Estate firefighter Hatcher Edgemon, “We just did keep it from the main part of the mill. The flames were so hot that it popped the glass right out of one of our trucks.”

That was pretty much it for the Hicoria mill. Although it was not a total loss, the once bountiful pine forest was nearly exhausted. It wasn’t worth Sherman’s investment to rebuild. So, like some sort of lumberjack circus, the company soon pulled up its tent posts and left town. They launched a new sawmill in Osceola County, and most of the town’s population followed them.

In 1937, a newspaper ad listed the remains of the old sawmill for sale. The leftovers included “1,000,000 feet of lumber consisting of siding, sheeting, flooring, ceiling, framing, heavy timbers, 1000 doors and 1000 pairs of sash.” Today, the only remnants of its massive footprint are a series of concrete footers and piers from its foundation.

Post-Lumber Era

Hicoria shrank by almost 80% in just a few months. The once bustling little town was sleepy once more. Its commercial buildings could no longer be sustained. A few locals remained employed at Archbold. The flattened pine forests to the west became excellent range land for cows. The ridge to the east of Hicoria prospered again as citrus groves.

But Hicoria never got its groove back. Gradually, most moved away to Lake Placid or beyond. The post office was shuttered in 1942. The school closed after 1945, and the children were bused to Lake Placid.

Development was threatened, especially during the second land boom in the 1960s, but it never came. Besides Archbold and agriculture, the only other industry in Hicoria was a state prison camp. It gained notoriety statewide in 1942 when a guard was charged with murder after he beat a convict with a wooden stick in 1940. There was a brief glimmer of a Florida oil industry, with test wells drilled near Hicoria, but those never proved productive.

Today, the land along the west side of the railroad tracks, including the old sawmill location, has been added to Archbold Biological Station. Between the tireless work of Archbold, state parks, and the water management district, much of this beautiful country has been set aside for preservation. As a result, it is starting to resemble what the first settlers saw. Bears and maybe even a few panthers again roam.

There are probably a dozen homes along Old State Road 8, north of Hicoria Road. There is a cattle ranch and plenty of orange groves unless greening takes them all out. And that’s it!

Practically speaking, there is no Hicoria. No sign welcomes you to town. There are no stores, even along US Highway 27. Even their mailing addresses read “Venus, FL 33960.” There is no sign of development on the horizon. And, you know what? That’s exactly how the 50 or so residents would like to keep it!

Sources

- Archbold Biological Station

- Sherman’s Mill Concrete and Questions

- Archbold Biological Center National Historic Landmark Filing

- Heartland Heritage (Tampa Tribune) by Teresa Stein: January 21, 1989 | March 29, 1986 | March 16, 1992 | July 23, 1994

- Heartland Heritage (Tampa Tribune) by Dave Nicholson: April 14, 1980 | January 4, 1982 | January 10, 1983

- Hicoria Mill sold off, ad in Ft. Myers Newspress 1937

- Hicoria post office in the middle of the woods, Tampa Tribune 1926

- Highlands County Golden Jubilee (50th anniversary) program, 1974

- Brief History of Hicoria by Charlotte Wilson, 1995

- Alexander Blair biographical paper by Fred Lohrer (2006) for Archbold BC

- John A. Roebling II biographical paper by Fred Loher (2006) for Archbold BC

- Various Florida State Roadmaps and Census Maps 1920-1940

- US Census and Florida Census Records 1920-1945

- Hicoria Prison Guard Charged with Murder, Tampa Tribune 1942

- Ceyton Carlton gives two acres for school, Tampa Tribune 1922

- Ceyton Carlton to open small sawmill at home, Tampa Tribune 1916

- 7350 acres sold off in Lake Placid and Hicoria region, 1954

- Work on Roebling Estate, Orlando Sentinel 1934

- Red Hills Groves purchase, Tampa Tribune 1919

- Highway Through Hicoria, Miami News 1926

- Building a road to Hicoria Post Office, Tampa Tribune 1934

- Nita Sapp, principal at Hicoria, Tampa Tribune 1933

- Peters and Kelsey teachers at Hicoria, Tampa Tribune 1930

- Hicoria fraudster, pronunciation HICKoria, Palm Beach Post 1919

- Hicoria and Venus Cattle Communities, Tampa Tribune 1941

- Anglin Family Robs Hicoria Station, Tampa Tribune 1934

- Fires: February 1932 | May 1932 | June 1935

- Archbold Seminar Series: Brief History of a Ghost Town

- Hicoria Community Points Map

- Archbold Blog