Winn-Dixie and the Davis Family

Boldness and tenacity took Winn-Dixie from a single store in Miami to a multi-billion dollar grocery empire.

William Milton Davis didn’t always win at business but wasn’t afraid of failure either. The founding father of the Winn-Dixie grocery empire was intense and opportunistic. And he instilled these same business principles in his four sons: James Elsworth (“J. E.”), Milton Austin, Tine Wayne, and Artemus Darius (“A. D.”).

The senior Davis was decades ahead of his time. In ways that would make today’s Lean Startup practitioners proud, the Davis family learned as much or more from mistakes as their successes. But when a hypothesis was proved, they weren’t afraid to (literally) bet the house on it. They employed these methods (and an insatiable tenacity) to propel them from a single store to a multi-billion dollar supermarket behemoth.

Origin of an Empire

William Milton Davis was born in 1880 in Texas and moved to the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas at a very young age. There, he was raised on the family farm. As a young man, he helped his dad manage the family’s general store in Gamaliel. In 1904, he cut his teeth with his own store in Henderson, the neighboring tiny town just across the Norfolk River.

Hearing fortunes could be made in Idaho, he moved with his brother Newton Carlisle Davis (“Carl”) to Burley in 1912. The following year, the brothers began working at Clark Mercantile General Store. Before long, the ambitious duo bought the place and renamed it Davis Mercantile.

And business was good! Three years later, they expanded to an 8,250-square-foot retail space called Davis Department Store. They sold everything from food to clothing. In a few short years, William and Carl grew the business tenfold, from $30,000 to $300,000 in annual sales.

As was standard for the time, they offered customers sales on credit—and even home delivery to boot. Their patrons lauded this practice and keen attention to service. The brothers were well-respected pillars of the southern Idaho community.

However, in 1920, competition steamrolled into town. An upstart chain called Skaggs Cash Store (the predecessor of Safeway) shunned credit and required cash-only purchases. This less risky model allowed them to lower prices on foodstuffs while offering a more extensive selection.

Then, a 1921 recession hit Idaho’s largely agriculture-based economy hard. Farmers suddenly could not pay off their grocery debt. The Davis store had extended tens of thousands of dollars in merchandise on credit, with no foreseeable return. Combined with the competition from Skaggs, they soon were forced to hand over assets to creditors and close up shop.

Undeterred, Carl encouraged William to check out the feverish Florida market, which was in the midst of the great boom years. Perhaps he was equally motivated to put as much distance between himself and Skaggs as humanly possible! Regardless, he took his brother’s advice and moved from the west coast to Miami in 1925.

“No” is just a temporary setback

With a $10,000 loan from his father, William surveyed the exploding market around Miami. He finally focused on the emerging community of Lemon City—today is Little Haiti—which was starting to blossom as a commercial and residential district just north of downtown.

Proud and determined, Davis walked into Rockmoor Grocery at the corner of Dixie Highway (now NE 2nd Avenue) and 59th Street on November 15, 1925. He confidently approached store owner C. A. Rhodes with an unsolicited offer to buy the store on the spot.

Rhodes scoffed at first. He had no interest in selling the shop. Miami was bursting with growth, and the business had netted Rhodes $6,000 that year. This was in the era when $1,400 was a solid annual salary!

Legend has it that Davis got a gleam in his unwavering brown eyes. He opened his briefcase and spread $10,000 in cold, hard cash across the cashier’s counter. He repeated his offer. Rhodes looked down at the money, looked up at the balding veteran grocer, extended his hand, and exclaimed: “SOLD!”

The store proved even more successful under Davis’s leadership. The following year, his sons James and Artemus dropped out of the University of Idaho to help their father run Rockmoor Grocery.

Learning lessons from Idaho, William vowed never to sell merchandise on credit and promised to fire anyone who did—“even if their last name is D-A-V-I-S!” Thus, they entered the trend du jour among groceries: the self-service, low-margin, high-volume game.

At store number one, they sold homemade pies baked by Ethel Davis herself (wife of William). By maintaining his relationship with previous vendors, Davis was the first to introduce Idaho potatoes to Florida tables. They focused on fresh produce, dairy, and meat from local farms—except for beef, which Davis insisted on importing from high-quality Western stock.

Following the Skaggs model, melded with his intense focus on customer service, they found great success at their Lemon City location. However, Davis never wanted to own just one store. He aimed to create a large retail chain; less than a year later, he started adding new locations.

They had a few false starts with store number two. Several attempts opened and closed quickly. Davis saw little reason to hesitate to pull the plug if an idea or location wasn’t working out.

Their first big break came when opening store number three in Hialeah. It was located on Lindsey Court, just north of the old post office near 54th Street (now known as Hialeah Drive). This location became a cash cow and immensely helped to finance early expansion.

In 1927, Davis’s store was rebranded as Table Supply Stores, and a phase of measured growth began. They steadily scaled out, opening moderately performing stores around Miami-Dade before entering the Fort Lauderdale market in 1929.

Standards and efficiency were the name of the game. Table Supply opened a 15,000-square-foot warehouse in the Wynwood district of Miami. The central hub was located near the train tracks. The facility supplied their stores with daily truck shipments, allowing them cheap “by the carload” prices.

They focused on creating uniform best practices in all of their stores. Each location featured a nearly identical layout with three departments: meats, groceries, and produce. They boasted novelties like electric refrigerated display cases, wider aisles, low shelves to keep everything in easy reach, and distinctive can pyramid displays.

Finding Opportunity in Dark Times

Despite the nation entering the early stages of the Great Depression, business was booming for Table Supply in 1930. With reported year-over-year earnings up over 100%, they decided to double down on expansion.

In the fall of that year, they opened three stores in Palm Beach County, where they met their greatest success yet. In its first week in business, the West Palm Beach location produced $7,600 in gross sales. For context, a typical take for a local grocer at that time was about $1,000.

Their most significant demand driver was selling quality cuts of Western beef at significantly discounted prices. While most meat markets sold steaks from 60 to 85 cents per pound, Davis offered it for just 19 cents! This created a bit of a frenzy (and often long lines). They started earning their future mantra, “The Beef People,” in the very early days of the store!

However, the business community in the Palm Beach area was not very happy to see Table Supply enter their territory. While they did not appreciate the chain’s competition, they had a downright fit when area manager Artemus Davis launched a November 1930 advertising campaign.

Newspaper ads throughout South Florida purported that Table Supply offered “the same steaks” that other grocers offered for less than a third of the price. Enraged rivals filed a series of false advertising lawsuits against Table Supply, claiming that the Davis beef was not “the same” as theirs.

Table Supply eventually won all the legal challenges and ultimately benefited from the suits. The charges were widely reported in newspapers, magnifying the advertising campaign and ensuring locals knew where to get the cheapest meat products! Eventually, the other grocers and butchers were forced to lower their prices too.

Flush with cash from their rabidly successful foray into Palm Beach County, the Davis family made a bet on expanding while the nation’s economy declined. In 1931 they bought another Florida chain called Lively Stores, giving them a total footprint of 33 locations and introducing them to the massive Tampa Bay market. The following year they added 10 Orlando area locations in the acquisition of B&B Stores.

No Time to Mourn

In November 1934, founder William Milton Davis fell sick during a church service. He went into emergency abdominal surgery the next day but succumbed to complications from the operation and heart disease a week later. He was just 54 years old.

Following their father’s death, the four brothers took over the business. James became chairman.

The twenty-six-year-old CEO had little time to mourn his father’s death. With a fast-expanding business at the height of the Great Depression, independent shop owners and politicians alike began to look at chain stores with ire. These fat cats, they were sure, were responsible for all of their economic woes.

In April 1935, Senator Henry C. Tillman of Hillsborough County introduced the “Florida Recovery Act.” Its goal was nothing short of banning all chain stores from the state altogether. The proposal was met with surprising support, and its debate occupied most of the floor time during the spring session of both houses of state government. The controversy erupted into heated newspaper and radio editorials, political grandstanding, and extensive advertising campaigns by both sides.

Needless to say, its passage would have quite literally put Table Supply out of business. They hired lawyers and vehemently argued against it. The bill passed in the House but was ultimately amended and largely de-clawed by the Senate. The weakened version then stalled when it was returned to the House for re-passage.

However, to appease their base, they passed in its place new graduated licensing fees and gross receipts taxes that severely penalized chain stores. Table Supply, with its 34 stores, was in the highest bracket. They had to pay a $400 license fee per store (but only $10 if you had one location) plus a 5% tax on gross sales (versus half a percent for single-store owners).

In response, the Davis brothers founded the Florida Retail Federation (then called Florida Chain Store Association). Through this organization, retail chains collaborated to lobby against this and other similarly oppressive anti-business laws.

The Florida Recovery Act became a hot item on the political agenda again in the 1937 gubernatorial race. In round two, it had a 50–50 chance of becoming law. Understand the severity of its proposed impact…

In what some likened to building a business firewall around the state, it promised to expel every retail chain and forbid any non-resident ownership of businesses operating in Florida. This included mere shareholders! The largely Democrat-backed initiative sought to remove yankee influence and profit-siphoning from Florida, but by extension, it would also eliminate northern investment in the state!

Lucky for the Davis brothers, it once again failed after a series of alterations in the Senate. Gradually, as the Depression began to subside, the various anti-chain regulations and taxes were repealed one by one. The gross receipts tax was thrown out in 1941, but others remained in place until as late as 1953.

Davis Brothers Know How to Winn

By 1939 the brothers had amassed 43 Table Supply stores throughout southeast Florida, the Heartland, and the Tampa Bay area. Perhaps through their work in the chain store association, they became acquainted with fellow grocery magnate William R. Lovett.

Lovett was the president of Jacksonville-based Winn & Lovett. The company operated 73 stores in north Florida and south Georgia under the “Lovett’s” name and some Piggly Wiggly franchises.

Winn & Lovett began in 1920 with founders Lovett and E. L. Winn. By 1930 they began to consolidate from numerous small neighborhood stores to fewer “super-markets” closer to the modern self-service vein. At that time, Lovett bought Winn out and rebranded the chain Lovett’s Groceteria. The term groceteria was used in the era as a contraction of grocery and cafeteria, noting the parallels in the self-service nature of the up-and-coming concepts.

Lovett convinced the Davis brothers to purchase a controlling interest in his larger retail chain. In 1939, they mortgaged nearly everything they owned and bought a 51% stake in the much larger Winn & Lovett. A. D. moved to Jacksonville to take over as company president.

For the next five years, Lovett stayed on the board, and the two companies operated as separate entities. Then in November 1944, the Davis family bought out the remainder of the Lovett’s chain and immediately merged the two companies. Taking on Winn & Lovett as their combined corporate monicker, they relocated their headquarters to Jacksonville.

Interestingly, William R. Lovett was not done with the grocery business after they parted ways. He later bought a controlling interest in the troubled Piggly Wiggly Corporation. Among his investments in other industries like shipping, Lovett revitalized Piggly Wiggly and grew it to 1,000 franchises throughout the southeast — 200 of which he owned personally.

Keep Investing in What Works

Over the next two decades, the Davis family had an unquenchable lust for growth. Besides a few Lovett locations in south Georgia, the company had no presence outside of Florida. That changed in 1945 with the purchase of Kentucky-based Steiden Stores and its 31 locations. The Steiden stores, mainly around the Louisville area, continued to operate under its well-known local brand for the next decade.

The acquisition brought Winn-Lovett’s total store count to 149. The stores operated variably as Table Supply, Lovett’s, Steiden, Piggly Wiggly, and Economy Wholesale Grocery, with a handful operating as Economy Wholesale Grocery.

By 1949, another grocery powerhouse with Miami roots had emerged. In just ten years, Margaret Ann New Era Markets had grown exponentially, opening 47 stores in the southern half of the state on both coasts.

Margaret Ann was founded by Robert Pentland, a Miami accountant and Air Force officer. Though it was named for his young daughter, its marketing suggested a fictional store founder: a housewife who truly understood their needs. In contrast to trendy new supermarkets that touted frills and fancy finishes, Margaret Ann boasted its unadorned simplicity and smaller staff, supposedly allowing it to offer lower prices.

As the Margaret Ann market share grew, Winn-Lovett seethed to see this ascension in their own backyard. So when a bit of weakness and disgruntled shareholders began to plague the newcomer, the Davis brothers did not waste any time taking advantage. They bought out the competitor for $5,000,000 and secured its spot behind A&P at the top of the Florida grocery market.

Through the forties, the two primary Winn-Lovett brands (Lovett’s and Table Supply) had worked hard to embrace the perks that Margaret Ann had shunned. They introduced coffee bars, handsome displays, and decorative flair into their buildings. Their mundane features like air conditioning, shopping carts, and well-staffed meat departments were all novel at the time.

For a while, they continued to expand all three core brands (plus Steiden in Kentucky), often in the same region. For a short time to create differentiation, Margaret Ann became the designator for its smaller stores. Some of the older Table Supply locations were also remodeled under that name.

Across all of the labels, Winn & Lovett had reached 178 stores by 1952. They applied for an initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange to fund their continued growth. That February, they became the first Florida corporation to be publicly traded.

Investors enthusiastically received the IPO. As one of the fastest-growing chains in the nation and with the ticker symbol WIN, there was a lot to like!

Their luck improved even more in 1953, when Florida repealed the gross receipts tax. This tore down the last remnant of the Great Depression-era anti-big business laws.

Flush with cash from stock sales and tax savings, they expanded rapidly into new and existing markets. And because, apparently, they needed yet another brand in their portfolio: they launched Kwik Chek. Most of their new and modern locations began to take on this newly-minted name.

Older readers will surely still remember these stores; however, even those my age will recall its iconic imprint that is still evident today. The check in the modern Winn-Dixie logo and its line of Chek colas owe their lineage to it.

Throughout the next decade, the Kwik Chek brand gradually became the more prominent of the bunch. Over time, all of their stores gravitated toward Kwik Chek, first with co-branding and then phasing out the older name. On a large scale, this happened across virtually all remaining Table Supply and Margaret Ann stores in 1955 and with the Louisville, KY area Steiden locations in 1956.

The Winn-Lovett buying spree really got kick-started from 1954 through 1957. They added these to chains to their lineup in quick succession:

- Wylie & Company, operating 8 Jitney Jungle stores in Alabama

- Eden’s Food Stores in South Carolina, 33 stores

- Ballentine Grocery Stores in South Carolina, 16 stores

- Penny Stores in Mississippi, 8 stores

- Ketner-Milner of North Carolina, 24 stores

- Kings Outlet Stores of Georgia

- H. G. Hill’s of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, 42 stores

- Dossett’s in Mississippi

In addition to gobbling up other chains, by 1957, they were buying 5–7 independent grocers per year. Meanwhile, they were opening 40–60 new stores and closing 20–30 underperforming locations annually.

Whistling Dixie

By the mid-fifties, Dixie-Home Super Markets were the dominant grocery brand in South Carolina, North Carolina, and parts of Georgia. Its roots date to 1927 when J. P. Williamson founded Dixie Stores; Robert E. Ebert and H. H. Harris started Home Stores in 1930. The two merged in 1937.

Winn & Lovett wanted desperately to break open the Carolina market and become the king of the Southeast. So, in 1955, they negotiated a blockbuster deal to merge with Dixie-Home in a stock swap.

The deal combined Winn-Lovett with its 271 stores and $260,000,000 in revenue with Dixie-Home’s 117 locations and $80,000,000 in sales. The combined corporation was renamed Winn-Dixie.

The Davis brothers were obviously thrilled out of their minds. They had far exceeded their father’s wildest dreams. The poetry of the merged name was the icing on the cake. They had long aspired to dominate the southern market or “win the Dixie.” Now it was built right into their corporate identity!

About a year and a half after the Dixie-Home merger, they renamed Winn-Dixie stores in the Carolina market. Gradually they phased in the new name across all of their stores; some were a hard cut over and others transitioned with evolving logos and co-branded stores for a while. However, in many markets, the Kwik Chek name survived into the late 1970s.

(Not) All in the Family

In 1965, the company promoted longtime VP Bert Thomas to the role of president, the first time someone not named Davis was at the helm. The brothers continued as the corporation’s largest stockholders and held the top positions on the board of directors — J. E. Davis remained the chairman.

By then, of course, millionaires many times over, the Davis brothers had become active in the Florida political scene. Since the family owned several private jets, they “generously” leased one of those to the state of Florida for just $1 per year in the late sixties. That benevolence, of course, helped curry them significant favor in Tallahassee.

The following year, Thomas announced a new milestone of one billion dollars in sales. The corporation operated 696 retail stores and 7 wholesale stores (under the Economy Wholesale Grocery line), stretching from Key West to Virginia to Indiana to Louisiana.

Uncle Sam is a Party Pooper

But in 1966, the federal government threw some ice water on the party. After a lengthy investigation by the Federal Trade Commission into the increasing conglomeration of power in the grocery market, it was determined Winn-Dixie was heating up too much too fast.

Under the Clayton Anti-Trust Act of 1914, Winn-Dixie was barred from acquisitions or mergers for the next ten years. The move wasn’t wholly unanticipated; as the country’s most profitable and fastest-growing grocer, most assumed the crosshairs were square on its back.

While it was a downer to visions of world domination, in some ways, it was more of a compromise than a punishment. Thomas sought to reassure shareholders that their internal growth would continue. Further, the decision removed any retroactive rollback of previous deals (which would have been a nightmare scenario).

“The principal practical effect,” Thomas said in the Wall Street Journal, “is to clear all Winn-Dixie’s past mergers and acquisitions from future challenge.”

Though slowed, the company brushed its shoulders off and opened new stores. Since the FTC’s jurisdiction stopped at the border, W-D turned internationally for growth in 1967. They purchased City Meat Market and its 11 stores in The Bahamas from owner Sir Stafford Sands.

The FCC’s ten-year ban finally expired in 1976. By then, they had adjusted to slower organic growth; however, opportunistic acquisitions resumed when the right deal came along.

One such opportunity was expanding into Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico. Almost immediately upon the moratorium’s expiration, Winn-Dixie purchased Kimbell Incorporated, which operated 135 stores in those three states under the trade names Buddies, Foodway, and Hagee.

A Third Generation

Then, suddenly, shock waves ripped through the company. Just days before the 1982 investor’s meeting, President Bert Thomas died of a stroke and heart attack at age 64.

Thomas’ leadership was lauded on Wall Street. He successfully navigated the FTC challenges and a changing market. Despite it all, he had lifted the company to well over 1,000 stores and year after year of uninterrupted top- and bottom-line revenue growth. Under his leadership, dividends (one of the only on the NYSE paid monthly) increased yearly.

Andrew “Dano” Davis (son of then-still board chairman J. E. Davis) was elected to replace Thomas as the corporation’s fourth president. Dano was just 37 years old when he was promoted to the post.

A year later, Robert D. Davis succeeded his uncle J. E. as board chairman. The third generation of the Davis family was now purely at the helm. However, Robert’s tenure was relatively short-lived.

After five years of flat growth, Dano replaced his cousin. While Robert remained on the board as vice chair, Dano served as President/CEO until 1999 and board chairman until he retired in 2003.

Damn You, Sam Walton!

At its peak around 1987, the Winn-Dixie empire included almost 1,300 stores and over $9 billion in gross revenue. It was the fourth-largest grocery chain in the country and had more than doubled since the FTC attempted to limit it two decades earlier. Its realm extended westward into Texas and Oklahoma and northward into Ohio and Indiana.

However, the eighties and nineties proved rough for the grocery industry, and Winn-Dixie was severely impacted. At one time, 20,000 square feet was considered a large store. However, with the advent of superstores during the 1980s, the new normal became 45,000 square feet.

With their all-in-one superstores, the Wal-Marts and Costcos of the world created pressure on the top end. Convenience stores like 7–11 were eating away at the small neighborhood store model. Plus, traditional grocer rivals entered the southeast (like Albertson’s, Kash ‘n’ Karry, and Food Lion). The Davis family was being squeezed on all fronts!

The increasing competition was a double-whammy: it ate away at Winn-Dixie’s customer base and created a race-to-the-bottom pricing environment. Grocers run a small-margin, high-volume game. It can often run as slim as 2–3% on regular food items. Leading up to the millennium, this razor-thin margin got even tighter.

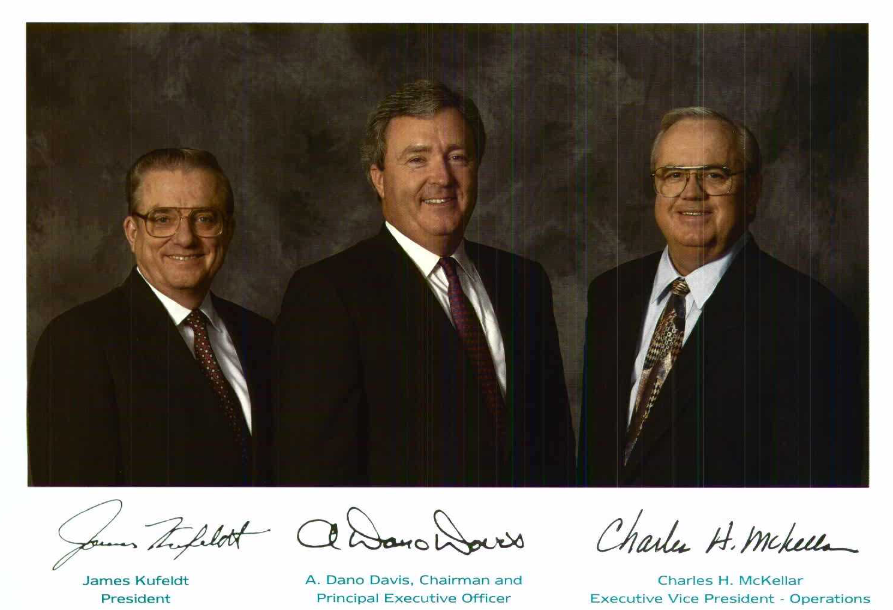

The board installed James Kufeldt as president in 1988. Kufeldt had spent his entire career at Winn-Dixie, starting as a produce manager in 1961 and working through the ranks. Under his tenure, the company needed to find its place in a rapidly changing market and chart a path back to profitability.

Under Kufeldt’s leadership, from 1988 through 1999, the Winn-Dixie store count trended downward. This was partly due to consolidating multiple aging stores in a locality into one larger store (sometimes as large as 55,000 square feet). They also closed down underperforming stores and even exited some markets entirely.

Winn-Dixie remodeled and enlarged existing stores. Where expansion was impossible, they would close the store and open a new one nearby. Since they signed multi-decade leases (company policy forbade owning real estate), they were often stuck for years paying rent on the now vacant space—at least until they found someone to sublease it.

In 1994 alone, the company spent $650 million on renovations to convert or open new Marketplace stores. Those capital expenditures made profitability challenging; however, the investments paid off. Gross revenue grew from $8B to $14B between 1988 and 1999, trickling down to a positive bottom line throughout the 90s.

Despite the wins, Kufeldt and Dano Davis butted heads over the company’s direction. Kufeldt was forced out, retiring in 1999. New leadership would take the helm for the turn of Y2K.

New Millennium

Market shakeups continued in the new century, with customer habits shifting toward bulk purchasing, big box stores, and even online. Despite move after move to modernize, gain efficiency, and improve its image, it was not enough to fend off the onslaught. The company’s revenue numbers slipped between 2000 and 2005, falling into the red. Winn-Dixie filed for Chapter 11 protection in 2005. The Davis era was officially over for the 80-year-old chain.

A year later, Winn-Dixie emerged with half the number of stores at its 1987 peak. Their territory was limited to Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

With the fat trimmed, they re-launched the stock ticker symbol as WINN. The leaner company’s profit improved, and they worked on fixing their image with fewer but remodeled, cleaner, modernized stores.

In late 2011, they were taken private when they were acquired by the parent company of Carolina rival Bi-Lo. The merged company was eventually renamed Southeastern Grocers, which retained Winn-Dixie’s Jacksonville headquarters as its home base.

As of November 2017, Winn-Dixie operates around 450 stores, mainly in Florida and the Gulf Coast. Its parent company, Southeastern Grocers, operates stores under the BI-LO, Harveys, Winn-Dixie, and Fresco y Más brands.

The Davis Legacy

Grocers stole — ahem, I mean borrowed — so many ideas from each other it is hard to say precisely who invented what. But the Davis family were absolutely true innovators in the space.

Revolutionary concepts pioneered by the three Davis generations have become so standard today that most people don’t even consider them. This foresight and experimentation played a significant role in shaping the modern grocery store. More generally, their imprint is felt in modern business theory.

Their corporate policy encouraged any manager at any level to introduce a new idea. Generally, they’d agree to try it in a subset of stores without adverse consequences if the experiment failed to give the desired result. However, if it had positive results, it would be implemented on a larger scale or chain-wide. This attitude kept the company at the forefront of the industry for decades, plus it created empowered and engaged employees.

This framework is considered a new theory among 21st-century business thought leaders, but the Davis brothers started using it over eighty years ago!

Outside of business, the Davis family has been an exceptional philanthropist, especially around Jacksonville, for many decades.

J. E. Davis gifted land and money to kick start the Mayo Clinic Jacksonville campus in 1986. The family has contributed tens of millions to fund Stetson and Jacksonville University business schools. Being lovers of social justice, they have also given millions to historically black colleges over the years and served on various boards. That generosity has continued to this day, with a two million dollar donation in 2017 to the Jacksonville Zoo.

Especially if you are an entrepreneur, you cannot help but be in awe of the legacy and accomplishments of these three generations of the Davis family!

This post is 3025 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.