What happened at N*****town Knoll?

Until the 1990s, this offensively named settlement appeared on Florida maps, but its origins were lost. Until now.

Warning: This article contains offensive racial slurs for historical and academic purposes. It will be kept to a minimum, but reader discretion is advised.

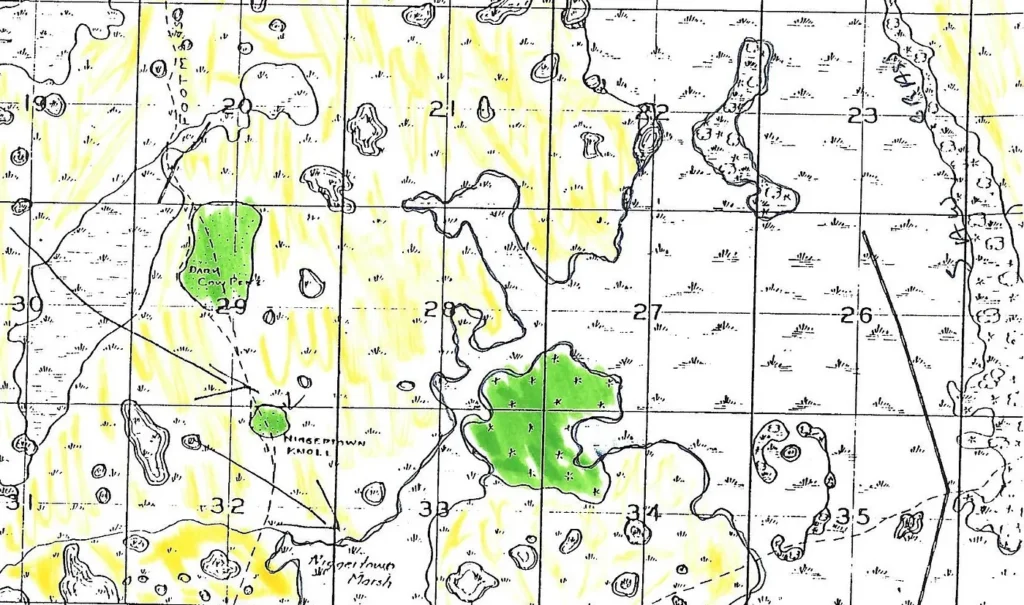

I’ll mention them only once in this article: Niggertown Knoll and Niggertown Marsh. These two offensive anachronisms survived on official government maps in Highlands County, Florida, until 1992, when public outcry convinced county officials to remove them.

Despite their vulgarity, the references preserved the legacy of the first African American settlement east of the Peace River valley. Ironically, without the politically incorrect name overstaying its welcome, the settlement would likely have been forgotten.

Its presence on maps, to the west of Lake Placid (out in the absolute middle of nowhere), has long intrigued me. Here we find this “town” utterly inaccessible by any public road today. Clearly, there had a story behind it! But what was this place? Who lived there? What happened to them? These questions have haunted me since I was a teenager.

Beyond tidbits of local lore, very little has ever been known about the hamlet until now. In this article, we’ll combine known pieces of the puzzle, examine the historical context of the lost settlement, and create new links that help tie it all together.

It all started with Bealsville

During the 1850s, settlers trickled into east Hillsborough County — between Plant City and Lakeland. Many of them, like the Wilder and Blanton families, were originally natives of southern Georgia.

The territory was newly opened to white settlers after the Seminoles had primarily been pushed into the Everglades. The federal government actively encouraged settlement through free homesteads of up to 160 acres in exchange for improving and defending the land for five years.

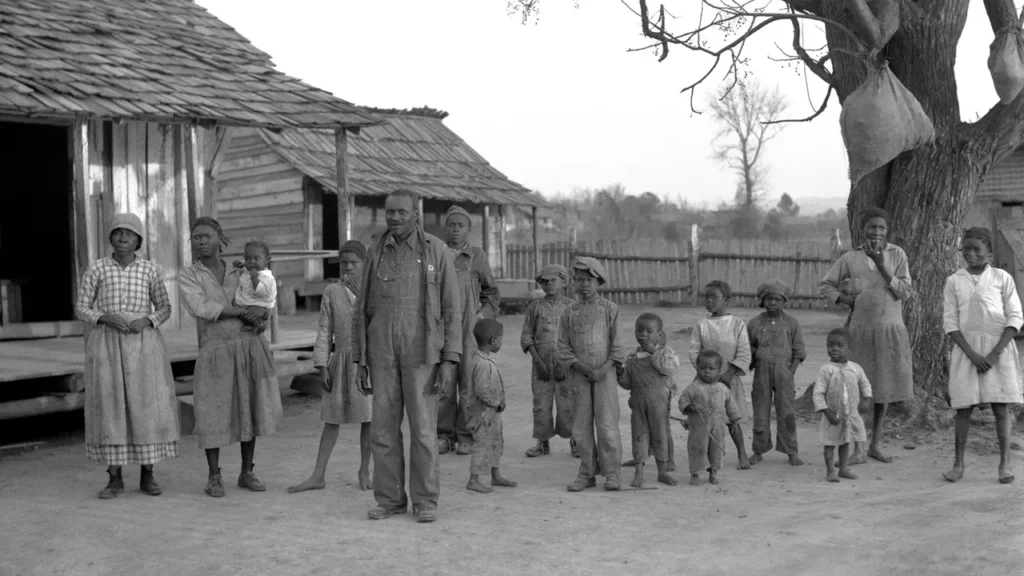

These farmers brought their slaves with them. Black men tended the crops, while the women cared for the home and children’s needs. According to oral tradition (of both whites and blacks in the area), the relationship between slaves and the families they served was relatively positive overall. Children of both races even played together.

Be that as it may, it still wasn’t freedom! When word reached the enslaved workers in the field that they had been declared emancipated, they exclaimed shouts of joy. They dug their hands in the dirt as free men and threw the soil up in the air in celebration.

These newly declared citizens immediately began to dream of owning their own land. They had seen firsthand that land alone was the ultimate source of wealth in the United States. They wanted to work in their own fields and create a self-sufficient future.

Local plantation owner Sarah Howell allowed these families to stay on her property until they could acquire and clear their own plots. She supplied them with horses, a mule, hoes, and a plow to get them on their way.

On December 24, 1865, the former slaves moved off of the Hopewell plantation and to their own town site. This black-owned village was initially called Howell’s Creek and later Alafia. It was officially renamed Bealsville in 1923 in honor of lifetime resident and prominent citizen Alfred Beal.

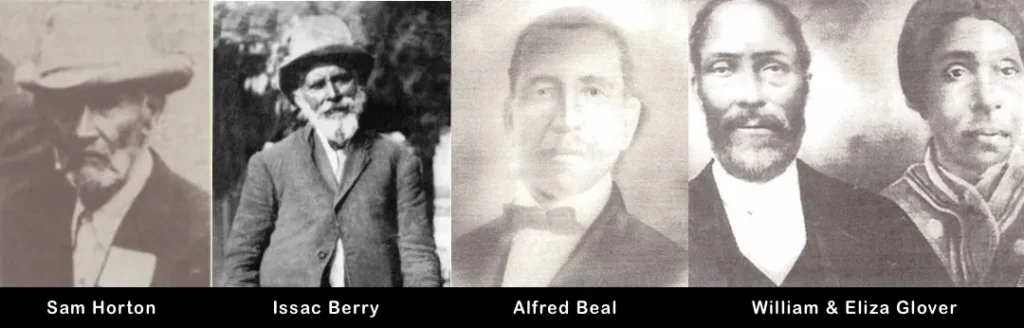

Locals recognize the founding families as Peter Dexter, Bryant and Sam Horton, Roger Smith, Robert Story, Isaac Berry, Mills Holloman, Mary Reddick, Jerry Stephens, Sam McKinney, Neptune Henry (Hendry), Steven Allen and Abe Seconger (with various alternate spellings).

At least a dozen Bealsville families secured 40–160 acre tracts under the Homestead Act of 1862. Applicants had to travel to far-away land offices, pay fees, and provide extensive documentation showing they had met all five-year requirements. The process was especially challenging for poor families; nationally, only 15% of black applications were granted. Bealsville residents were exceptional in their success.

Due to the stringent requirements, not all residents could secure a land grant. The townspeople worked together and pooled their money until each family had a plot. Many continued to add to their holdings over the following decades and turned their plots into profitable farms that sustained them for generations.

To this day, some of the original families reside on their ancestral homesteads. The remaining few families fight to maintain their heritage and way of life. Let there be no doubt: their great-great-great grandparents were skilled agriculturalists and models of strong work ethic.

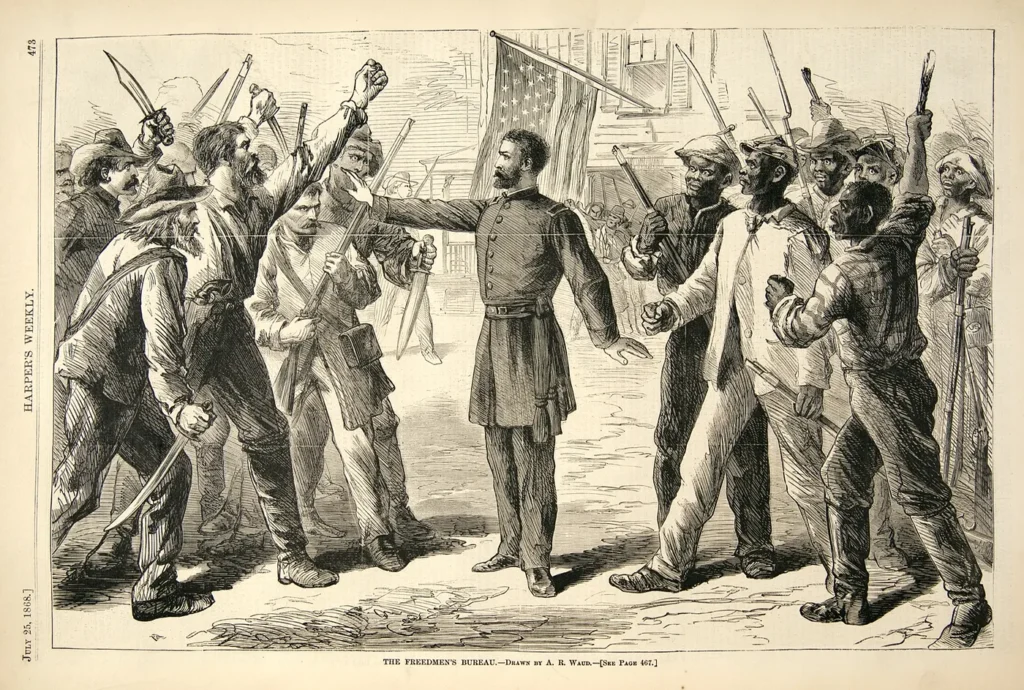

Reconstruction Sparks Fear

Blacks and whites in the immediate Plant City area had a relatively peaceful relationship after the Civil War. And the residents of Bealsville showed early signs of being prosperous on their new land. Still yet, for many, all was not sunshine and roses.

Reconstruction was harsh for the South, and eastern Hillsborough was no exception. The economy was in shambles, and no one knew how society would function without slave labor. Unwelcome northern “carpet baggers” moved in, and strict regulations were imposed on Southern states.

Rumors swirled that Southerners were planning to fight back and reinstitute slavery. This wasn’t just gossip; a movement of white men called the Redeemers was actively trying to trample Yankee interference and the “uppity” blacks who demanded equal rights.

One of the Bealsville residents, Neptune “Nep” Henry, got wind of the Redeemer movement. He was a former slave of the Blanton family, who selected the location of the first church at Bealsville in 1868.

Nep is described as very tall and slender with an outspoken temperament. He was just the kind of black man who made white folks uncomfortable; they preferred the “yes, massa” attitude.

With hindsight, one can hardly blame Neptune for his distrust of the whites who formerly had enslaved his family. However, it was likely for this reason that old-timer Kelsey Blanton recalled Nep as “suspicious and unreliable” in a letter he wrote to historian Albert DeVane in 1955.

Terrified of the prospect of being re-enslaved, Neptune was convinced they needed to flee. His charisma and leadership compelled several early residents of Bealsville to join him on the search for a new homestead further south.

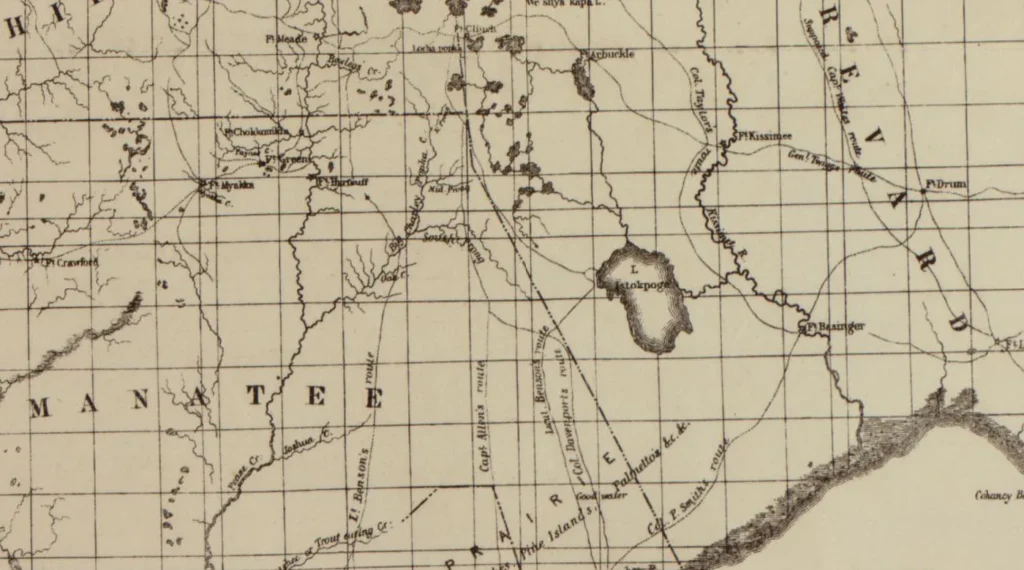

The Footman Trail

The Yankees moved into South Florida to interrupt the cattle trade as the Civil War raged. They sought to do primarily three things: 1) Cut off the Confederates from the Cuban market, 2) Stop the flow of cattle to feed Confederate troops, and 3) Feed their own armies with seized cattle.

In response, the South formed the “Cow Cavalry” in 1864. William Footman of Leon County was designated the executive officer to raise this volunteer force of farmers and cow hunters.

The state’s interior, especially south of Polk County, was impassible with any efficiency. It went from sugar sand scrubs and prairie to mucky bogs. The only roads to speak of were cattle paths and old military trails from the Seminole Wars. The native sons of the Cow Cavalry knew this terrain well.

One such trail, first called Davenport Road, stretched from Fort Meade to Fort Thompson (LaBelle). It was named for Colonel William Davenport during the Second Seminole War around 1839. Later the vast territory became a primary range for “Cattle King” William B. Hooker, who set up cattle pens near Highlands Hammock State Park (then known as Hooker Hammock) and led forces down the trail during the Third Seminole War around 1857.

During the final stages of the Civil War in 1865, Major Footman led his Cow Cavalry down this route for a would-be surprise attack on Fort Myers. Despite the regiment ultimately returning to Fort Meade defeated and half-starved, their general path remains on some maps even to this day as Footman Trail.

First Settlement in Highlands County

Neptune Henry led his cohorts down this military road into the vast wilderness of a new colony around 1870. It is unclear how many accompanied him, but Blanton indicates 10-year-old Sam Horton was among them, most likely accompanied by his parents, Bryant and Olive Horton.

What is now Highlands County had a population of zero (the Census didn’t track Seminoles). After leaving Fort Meade, Neptune’s group passed the vicinity of embryonic settlements at Popash and Crewsville. Outside a clearing at Hooker’s Cow Pens near Highlands Hammock, they’d have seen nothing but scrub and cypress swamp in two to three days of travel.

Feeling sufficiently insulated from the closest white community, they finally stopped at a high point along the road. They built their village on a slight rise between Footman Trail on the west and Fisheating Creek to the east. It likely consisted of little more than a tiny cluster of one-room shacks.

They cleared a small plot of land for farming, using their decades of agricultural experience. Game was plentiful in the virgin wilderness, and the meandering creek supplied ample fish.

However, if they had hoped to never see a white man again, they would have come to the wrong place. Although the closest real town was Pine Level, the pioneer county seat of Manatee County near the Peace River, the Footman Trail was a regular thoroughfare for cowboys driving their cattle south to Punta Rassa.

Just north of N*town was a dry, flat portion of prairie that was a frequent overnight camp. It is known by pioneer descendants as “Dark Cow Pens,” supposedly because they aimed to get their cattle there before dark. I would suggest perhaps its origin has more to do with its one-time residents, my theory being it was actually once “Darkey Cow Pens.” While I have no proof of this, it was less than a half mile north of N*town Knoll.

Some oral traditions suggest that cowboys once stopped there. They were watered and fed and perhaps traded with the townspeople. It would have been a convenient outpost.

The tales passed down by Highlands County pioneer families are shaded by a white perspective. These recollections refer to them as “squatters” and say they were lazy and wanted an easy life. Facts seem to dismantle that theory.

Their heritage from the hard-working and homestead-desiring population at Howell’s Creek/Bealsville negates this fallacy. The fact is that at that time, whites were also squatters. These black pioneers sought to settle and clear land to file for 160-acre homesteads, just as their brethren in Hillsborough County did. White settlers did precisely the same.

Collapse of the Colony

Ten miles further south along the Footman Trail was a Seminole camp along the Fisheating Creek near what is now Venus. According to Blanton, the Muskogee-Seminole chief Chipco sent word to Plant City that the black colony was on the brink of starvation.

When the Wilder family of Socrum (north Lakeland) heard of this, they had compassion for their family’s former slaves. Reportedly, they hastily headed down there, brought the Horton family back, and returned them to the Howell’s Creek settlement.

The reason for their struggle for survival is unclear. Perhaps the scrubby soil was less accommodating? Maybe they faced a harsh winter? Were they unable to hunt, fish, and gather enough to subsist?

Ches Skipper, son of Jonathan Skipper (perhaps Highland’s County’s first white settler), said the N*town residents “soon decided to abandon the ‘farming bit’ for a more relaxed way of life.” That bit of cowboy colloquialism was to assert that they began to steal cattle and crops.

Assuming this cracker legend is true, perhaps desperation was the cause rather than simple idleness.

Skipper continued that “after letting this go on many years,” the cattlemen decided to do something about it. “The Colliers and some others” loaded their guns, mounted horses, and confronted the Knoll residents. He says the white mob “went down and cleaned ’em out.” Other tellings indicate the entire village was burned to the ground.

Cleaned Out

Cleaned ’em out… That revelation deserves a solemn and dramatic pause.

Although swift and severe vigilante justice for cattle rustling was quite common in those days (regardless of race), this visual of smoking guns and a smoldering town seems horrendous to modern sensibilities. The tale rings of another Rosewood or Ocoee-style massacre. If any colonists were killed, it would also represent the only known lynching in what would become Highlands County.

However, does “cleaned ’em out” actually mean shot and left for dead? By most interpretations, the answer is hushed but knowing “yes.” But could it be possible that the N*town residents were simply run off?

The rest of the story is somewhat unclear. And, of course, it is one of those tales folks are not apt to talk about these days. Maybe a family legend still told can fill in some of the gaps. It would be good to set history straight!

What is known, though, is Neptune Henry was not killed that day. He returned to Hillsborough County with his wife, Jane. They appeared in the 1880 Census, living next to the Hortons and Alfred Beal. In the next decade, Neptune was successfully granted an 80-acre land grant in Bealsville. He worked his land until he died in 1915; he lived to be 85 years old.

Be that as it may, this doesn’t necessarily mean all ended well. Perhaps Nep left before things got to that point? Or perhaps there is a reason three of his seven children disappeared between the 1870 and 1880 Census?

Unfortunately, we may never know the true fate of Highlands County’s first town. However, we should nonetheless remember these pioneer settlers. Their story should be told as part of local and black history.

Neptune and Venus?

As I wrote this story, I wished I had another name to refer to N*town Knoll. It would be nice to have one not chosen by pre-enlightened white men with racism running in their Jim Crow-era blood.

Surely, I thought to myself, its residents must have called the settlement something more pleasant. Perhaps they would have named it after their reported founder, Neptune.

Aha! Then it dawned on me. Maybe they did!

Now, this is purely unfounded speculation; however, the first “permanent” town in Highlands County is Venus. This tiny village, which still has a post office, is also located on Fisheating Creek and the Footman Trail.

Perhaps, rather than being named for a sawmill owner navigating home by following the “morning star” (as one legend claims), the farming community of Venus was so named due to its proximity with Neptune.

I have no idea. Just a theory!

This post is 2739 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.