The Marvelous Wooden Railroad

John C. Burleigh needed a steam engine for his sprawling sawmill in Avon Park, and nothing would stop him!

Imagine living in frontier Central Florida in the year 1895. Without roads or mechanical equipment, you must move a 12-ton locomotive across 23 miles of untamed flat woods. How do you do it?

That is the very problem that John C. Burleigh needed to solve.

The Connecticut native moved to Florida in 1886, joining his sister Gertrude Burleigh Simmons as one of the founders of Midland—now a ghost town halfway between Fort Meade and Frostproof. Burleigh served as Midland’s first postmaster, ran the general store, and owned the sawmill.

But around 1890, the 25-year-old decided that Martin Oliver Crosby was on to something in his new town of Avon Park. So Burleigh sold his holdings at Midland to his brother-in-law and opened a business in Crosby’s upstart village of about 200 people. His new steam-powered sawmill sat along the shores of Lake Brentwood, supplying the entire township and beyond.

And business was good! So good, in fact, that it created a big problem for the entrepreneur. The company logged all of the timber within a mile radius of the mill, making it no longer feasible to transport it by mule power from the distant forest to the factory.

So Burleigh had a decision to make: build a new facility further out into the pine woods (and further from town) or find a new way to transport the hardwood.

He discovered many logging operations in the north were using lightweight Shay locomotives. This technique reportedly cut the cost of stump-to-mill transport by as much as 65%, from $3.50 per thousand to just $1.25.

Burleigh ordered a used 12-ton truck made by Lima Locomotive Works in Ohio. A short time later, he received word that his shipment had arrived from Tennessee and awaited him at the Bowling Green train depot. Now, the fun would begin!

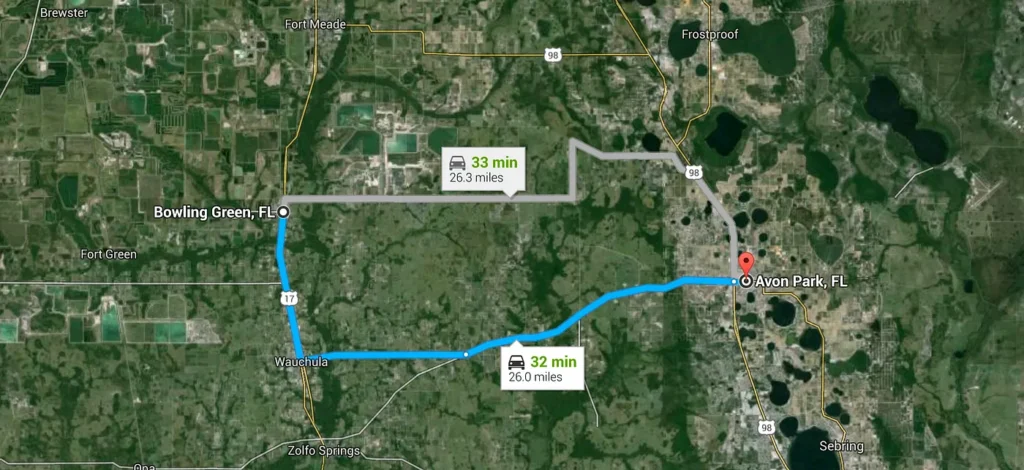

Today, it takes 30 minutes to travel by car from Avon Park to Bowling Green. But in 1895, the 23-mile journey took about six hours on horseback. Leaving the ridge highlands (130–150 feet above sea level) and heading into the Peace River Valley, one descended into numerous marsh areas — especially before the canals drained much of it for pasture and phosphate. The Peace River, Charlie Creek, Bee Branch, and other small waterways had to be forded along the way.

Now imagine the reverse of that journey: crossing the creeks, going up the ridge, and hauling a 12-ton steamer!

On December 13, 1894, Burleigh arrived in Bowling Green to receive his package. With him were 12 men, a cook, camping equipment, and a supply of 4×6 and 2×6 wood planks. They found the locomotive sitting on the bed of a box car, so their first task was to unload the train from the train.

They built a pattern of interweaved wooden trestles with planks to support the tremendous weight with a flat inclined plane leading to the ground. Once they got the beast in motion, Newton’s law of gravity did its part, and they ensured there was enough runway for the locomotive to halt at the edge of the forest.

The team then constructed rails from the 4×6-foot planks and eased the great engine’s wheels onto these makeshift tracks. Its 8-inch treads gripped the boards securely as they lay several feet more out in front of the truck.

“Give her some steam!” Burleigh must have called out to the engineer in the cab. The truck lurched forward slowly until it had abandoned the track behind it. The team then pulled up those boards from the back and hustled them to the front of the line.

In this manner, they continued. For nine days! The laborers inched along, covering less than three miles per day. They throttled her gently over the creeks. Carefully, they led her through the marshes, swamps, and wetlands. More quickly, she was pushed through the flat forests and scrub.

On December 22, 1894, John Burleigh’s twelve-man team arrived back in Avon Park to much pomp and circumstance. A large congregation of townspeople from Avon Park, nearby Pabor Lake, and other settlements turned out to see the completion of this incredible feat of human will. It was indeed a civic mark of pride for the region. Local dignitaries spoke, the band played, bells rang, and the train whistled triumphantly.

The permanent wooden track at the mill was constructed entirely from pine lumber milled at Burleigh’s facility. The rails were fastened with hardwood strips and held together with wooden pins. No nails or metal of any kind were used. It was laid along the ground and stabilized with ordinary sand as its ballast. The weight of a 12-ton train quickly embedded the track firmly into the ground.

The experiment was an unmitigated success. After several months of operation, the track or train had no accidents or repairs. Burleigh’s heavy logging locomotive regularly ran twenty daily trips over the tracks.

The town was so impressed that the Avon Park Transportation Company, which had long unsuccessfully lobbied investors to extend traditional rail lines to Avon Park, decided to shift its attention toward constructing a wooden railway under Burleigh’s design.

Seeking to raise a capital investment of $25,000 to fund the project, the group proposed to build 40 miles of wood tramway to either Haines City or Bartow. Burleigh was named superintendent of construction.

It was an ambitious project but significantly cheaper than a steel road. Northern railroaders marveled that the cost of the 40-mile proposed wooden tramway would barely be enough to build a single mile of traditional railroad. Not only could this venture open up a new portion of the state of Florida, but many experts thought it could potentially revolutionize the railroad industry as a whole.

Investment dollars were hard to come by after the two devastating winter freezes (December 1894 and February 1895). Focus began to turn to Bartow — rather than Haines City — as the line’s terminus, given the warmer reception from well-to-do business owners there.

Despite only having a fraction of the needed funding, construction began in June. On September 7, 1895, the first railway segment opened for business, reaching the Pabor Lake settlement four miles north of Main Street in Avon Park. The sister towns threw a grand celebration as the maiden voyage took 150 people northward that morning.

The exuberance and optimism were at an all-time high. All felt sure the line would soon touch the communities of Frostproof, Midland, and Buffalo Ford on its way to Bartow or Haines City. The Avon Park Transportation Company was sure any doubters would be satisfied once they rode the glorious if short, wooden railroad.

However, the funding did not come, and the wooden line never reached the county line. The mainline steel railroad finally extended to Avon Park sixteen years later, in 1911. Regardless, Burleigh and his compatriots’ determination and ingenuity were admired by many prestigious publications of the era (such as Harper’s Weekly) and should still be appreciated today!