The Lost Colony of Pabor Lake

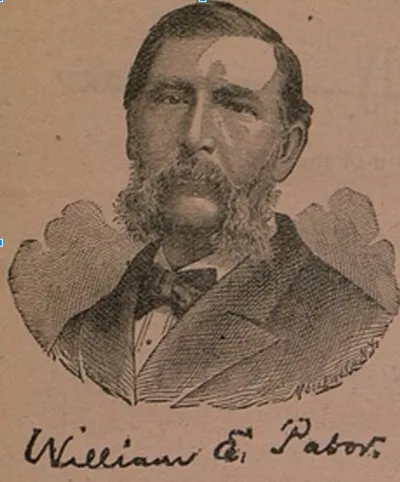

Most people interested in the history of Highlands County have heard about the involvement Melvil Dewey (of Dewey Decimal System fame) had on the founding of Lake Placid, Florida. However, few have ever heard of the Pabor Lake Colony, which was founded by another accomplished literary figure, William Edgar Pabor, as Highlands County’s northernmost town.

Before the 1890s there were no significant communities in what would become known as Highlands County. There was simply no easy way to access the southern section of the Lake Wales Ridge. The only roads were sandy trails at best and the railroads were still a couple of decades away from reaching Avon Park.

Despite the challenges, the beautiful lake-dotted ridge running south from Haines City began calling to pioneers with adventurous souls. Where others saw difficult and isolated terrain, these early settlers saw a blank canvas to build their own prosperous destiny.

Origins of a Founder

William Edgar Pabor was born in Harlem, New York in 1834 and rose to prominence at an early age as a poet and newspaper journalist. His poems were published nationally by the time he was 16. And while yet a teenager of 19-years-old, he was named editor of the weekly Harlem Times. In 1870 he left the City and — like many — headed to the frontier west. Pabor, along with his wife Emma and first son (William Helme Pabor), left everything they knew for the mountains of Colorado.

The well-known writer continued to see great professional success in the US territory (Colorado did not become a state until 1876). He helped to found many newspapers and organizations in the emerging Rocky Mountain region. A prestigious fraternity of journalism, the National Editorial Association, named Pabor its secretary and poet-laureate. During this time he published numerous books about agriculture and others featuring his poetry. His shorter works were published in newspapers, journals and other publications nationwide, and he built a strong reputation in the industry.

Despite his great love for Colorado and the wealth of respect and connections he had earned in the region, his health began to take a downward turn around 1890. His doctor recommended — as was common practice at the time — that he relocate his family to a lower elevation and warmer climate. After making visits to Honduras, southern California and throughout Florida, he concluded that the most ideal tracts lie in the “Lake Region” of Florida.

By the time he reached Florida in 1892, Pabor was no stranger to town-building. He had already been prominent among the founding pioneers of the Colorado cities of Greeley, Colorado Springs, and Ft. Collins. After that he was one of the first colonists of Colorado’s Western Slope, kick-starting the cities of Grand Junction and especially its suburb of Fruita. Through these efforts Pabor also became thoroughly knowledgeable in the areas of agriculture and irrigation.

Lure of the Pineapple

Although Florida agriculture is now primarily known for oranges, around 1890 it was the pineapple gaining the most traction in the southern half of the state. The tropical fruit is even more sensitive to cold than subtropical citrus and requires well-drained sandy soils. The Indian River area (between Vero Beach and Palm Beach) had built a strong reputation for the lucrative pineapple harvests during the 1880s. And most pineapple cultivation was taking place near the coastal regions of South Florida.

Even in these southern reaches of the state, winter freezes and frosts (such as a particularly bad one in 1886) had done great damage to citrus and pineapple crops as far south as Fort Myers. However, after seeing fantastic harvests near Avon Park (while coastal areas suffered from a winter frost) Pabor was convinced he had hit upon something huge!

The secret to the Lake Region’s “frost proof” nature, many in the area believed, lie in the perfect combination of latitude, altitude, and lakes. The entire ridge region, between the Peace River Valley on the west and Kissimmee River Valley to the east, sits high at 100 to 150 feet above sea level. Outside of Florida that may seem like nothing, but it is quite significant in the Sunshine State! In addition, the landscape is dotted by literally hundreds of lakes, both large and small. This not only provides fresh water for irrigation but helps to moderate temperatures.

The combination of the altitude and water can maintain temperatures as much as six to eight degrees warmer during cold snaps. These natural defenses can mean the difference between no damage and widespread destruction of frost sensitive crops, compared to localities just a few miles east or west.

Origins of a Town

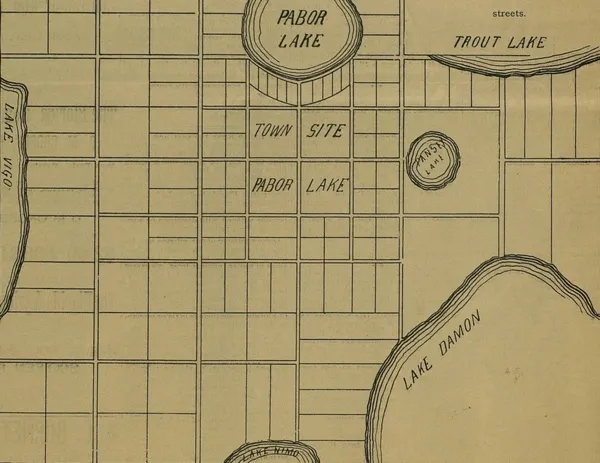

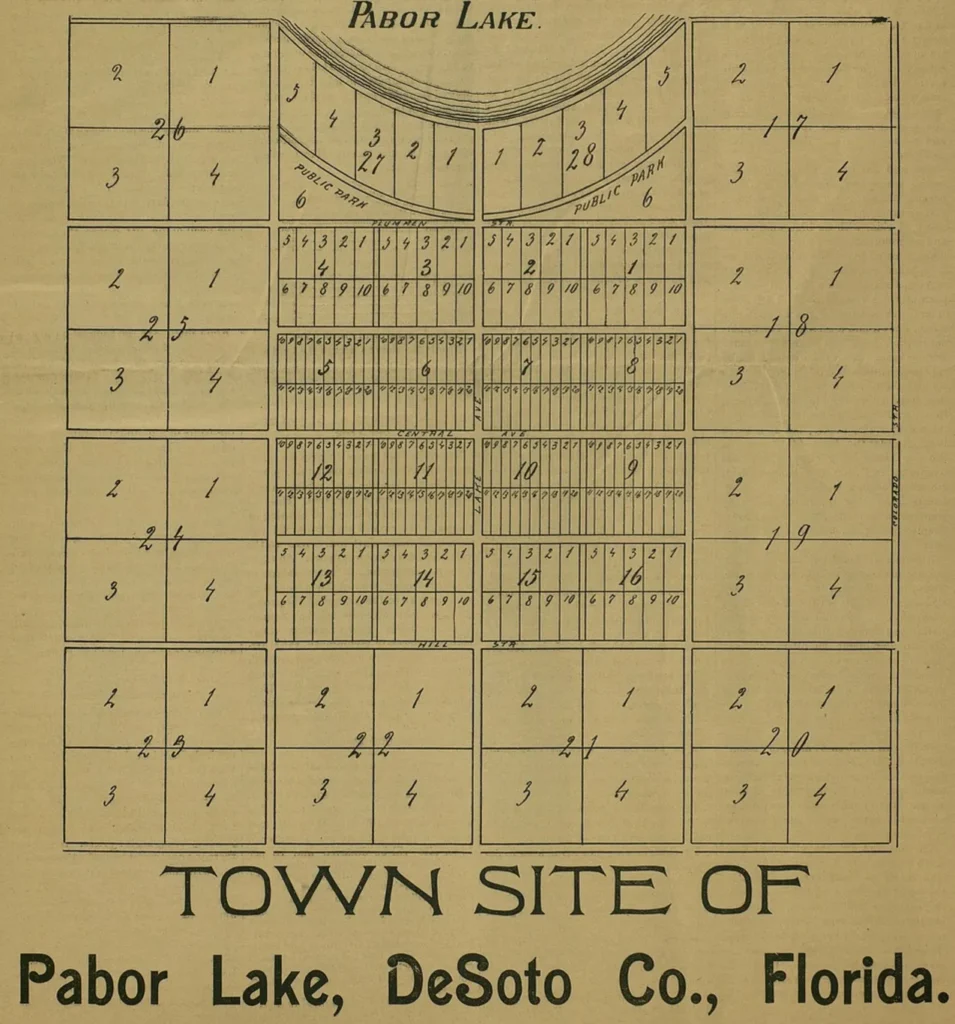

This map shows the location of the former center of the town site.

Oliver Martin Crosby first arrived in Highlands County in 1884, settling in an area he called Lake Forest — later known as Avon Park. The Connecticut native was a great promoter of his little town, and by 1886 he had convinced enough settlers to relocate there (from as far away as England) that Avon Park was incorporated.

The budding townlet featured a few shops, wooden sidewalks, and pine straw streets. Construction started on Avon Park’s Hotel Verona in 1887 and was completed in 1889, with its 32 rooms many days being filled to capacity.

On one such day in April 1892, William E. Pabor rode into this toddler of a community via a horse-drawn coach from Fort Meade. Perhaps first learning of the area in Crosby’s Florida Home Seeker publication, Pabor would later refer to Crosby as the “Moses” of the beautiful lake-filled township.

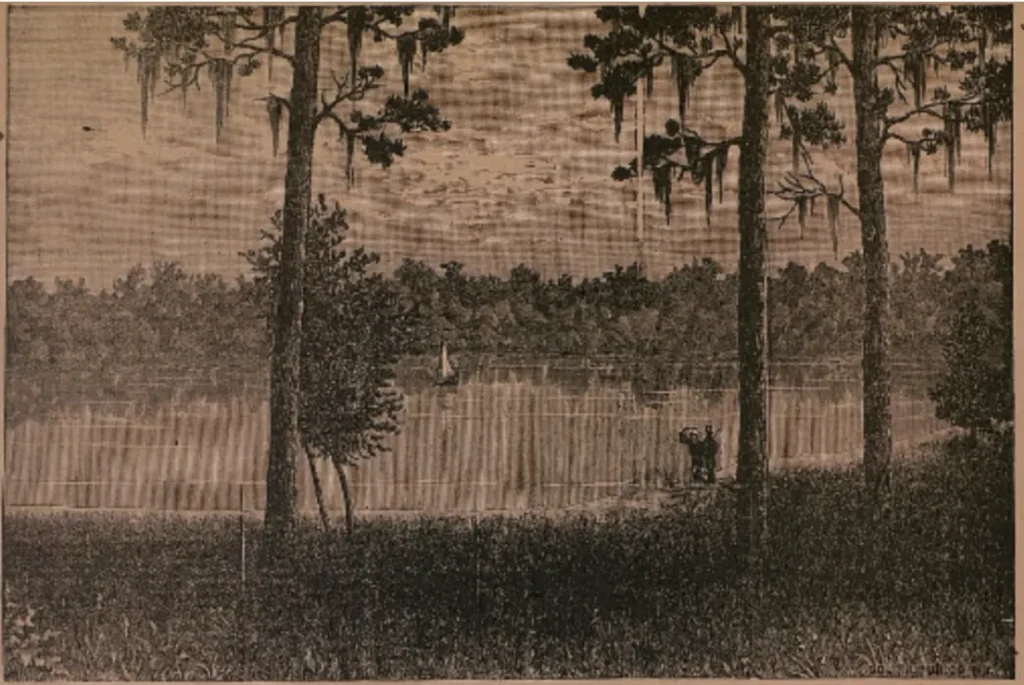

Lodging temporarily at the three-year-old hotel on the shore of Lake Verona, Pabor surveyed the surrounding lands with his son (William H. Pabor), looking for the perfect spot for their settlement. They finally came upon a serene area some four miles north of Avon Park, surrounded by seven lakes.

The two purchased 1,400 acres—over two square miles—from the Kissimmee Land Company. They spent that first night camping on the shores of a small unnamed lake, which the elder Pabor dubbed “Pansy Lake” after his 10-year-old daughter. As they slept under the stars along the banks that would later become their homestead, they dreamed of platting an agricultural town with upstanding citizens and profitable estates.

Visions of Eden

The town-building poet wrote home to Colorado (where his wife Emma, daughter Pansy, and three other sons continued to reside for the time being) and announced they had found it. One can imagine the two feverishly sketching plan after plan in their Avon Park hotel room, platting what their new Garden of Eden should be like.

Two sixty-foot-wide boulevards would bisect the center of the townsite. These six blocks of businesses and small home lots would serve as its hub, immediately surrounded by larger acreages of pineapple cultivation. Just to the north would be fine villas sloping down to the picturesque clear waters of Pabor Lake itself.

They planned to put ten percent of every property sale into a general parks and improvement fund. The younger Pabor located two massive oak trees, estimated to be at least 250 years old, within view of the south shore of Pabor Lake. These “Twin Oaks” would anchor a spacious public park between the business district to the south and the Pabor Lake villas to the north.

Their new property was bordered on all sides by the waters of the seven lakes: Pabor Lake to the north; Trout Lake to the northeast; Lake Pythias to the southeast; Lake Damon and Lake Nemo (now Lake Lillian) to the south; Lake Vigo (now Lake Adelaide) to the west; and the baby Pansy Lake nestled between. Though their land stretched northward into Polk County (with lakes Pabor and Trout straddling the two counties), the focus of the settlement sat on the Highlands County side (which was then part of DeSoto County).

Building in the Heat of Summer

One can only imagine the sweaty labor of clearing, chopping, and building under the hot, humid July conditions that only Floridians can fully understand. Their busy work was conducted without the help of any modern tractors or power tools that modern laborers now employ. Their only respite was the cool lake waters.

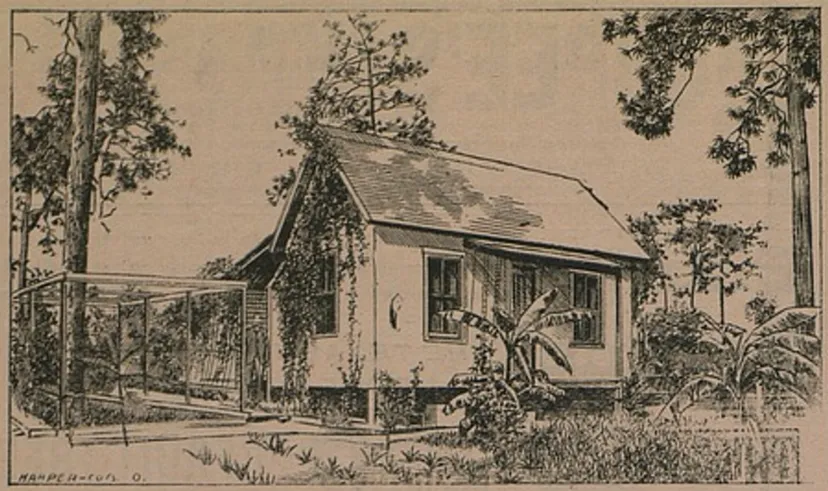

The original Pabor homestead, “Cozy Cottage,” as it would be referred to, was completed on July 18, 1892, in the middle of what is now a fairway south of five-acre Pansy Lake at River Greens Golf Course. A week later, they finished plowing their first field. Three days after that, the fertilized ground received its first pineapple slips!

Though now barely perceptible as a road, Lake Avenue served as the town’s primary north-to-south artery, running from Pabor Lake on the north to Lake Nemo (Lillian) to the south. Central Avenue was carved, running east-to-west from Pansy Lake to Lake Vigo (Adelaide), crossing Lake Avenue in the precise geographic center of the colony. Today, Central Avenue is still passable as the paved single-lane road known as Sun Pure Road.

A Citgo gas station and the former Hair Depot salon along US 27 at Allamanda Blvd betrays the southern terminus of Lake Avenue. The Cargill North America Juice plant, along US 27 North (just before you leave Highlands County), marks the western edge of the former Central Avenue thoroughfare.

Open for Settlement

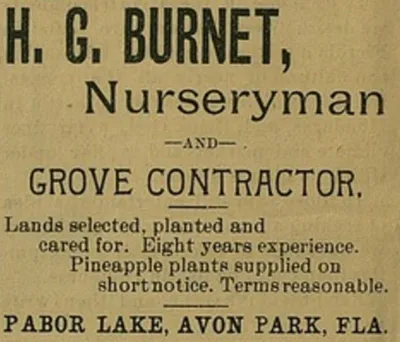

On Monday, August 8, 1892, the 58-year-old Pabor placed a notice on the wall of the Avon Park post office offering land in the new colony to prospective settlers. By the next day, H.G. Burnet was their first applicant, and the ink was dry on their contract by noon on Wednesday.

Burnet was a nurseryman from the Fort Myers area who was discouraged by the frost he saw down south. He believed the ridge would afford better protection and thus became the second settler at Pabor Lake, with a ten-acre tract on the north shore of Lake Damon. William H. Pabor built the Burnet cabin quickly, and the nursery was open for business!

Burnet supplied many of the colony’s seeds, slips, and fertilizer. More importantly, he became the community’s second-best advocate. With a solid reputation in agricultural and bee-keeping circles, his letters to popular farming publications extolled the virtues of the climate and soil composition around Avon Park, lending credibility to Pabor’s boasts.

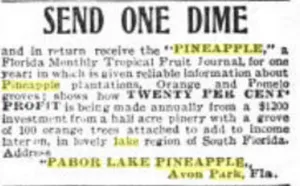

In October, Pabor began the next phase of his promotion for the new town. Despite having less than ten residents then, the journalist started to publish a monthly newspaper called the Pabor Lake Pineapple. It became a prominent voice in “pineapple culture” while simultaneously plugging the community and its latest news and developments.

Through traditional advertisements and exchange relationships with other papers, Pabor began canvasing the country. He beckoned to northerners with promises of virtual paradise on earth: health-promoting climate, frost-protected harvests, profit to be had hand-over-fist, and other such inane propaganda claiming mildly hot summers and little to no mosquitos. Let’s grant him some pardon by noting that such literary license with the truth was common in such promotions at the time.

Pabor aspired to create a tight-knit and upstanding town of intellectuals. He forbade saloons and drunkenness of any kind and insisted they had no desire for speculators. The founder maintained he would rather have slower growth with actual settlers than folks buying up land with no hopes of residing there.

There will be no effort to “boom” the place. One resident is worth twenty non-resident purchasers. One ten-acre tract cleared and set to fruit is of more account than twenty sold to Northern people who may desire them for speculative purposes.

Pabor Lake Pineapple — November 1892

The land contracts seemed to come in quite quickly, with 14 deals made by January 1893. However, despite his stated desires, the settlers were slow coming. Some merely saw an investment opportunity in real estate appreciation, others thought to hire the company to farm the land for them, and many others simply planned to relocate “sometime in the near future.”

The settlers did trickle into the colony, though, including the founder’s own family. Emma and Pansy Pabor joined the father-son team in November. The other sons followed a few months later.

Putting Pabor Lake on the map

One of the primary problems of the new settlement was simply getting there. Early instructions in the Pabor Lake Pineapple called for visitors to make their way by train to Jacksonville and stay a night or two at the Traveler’s Hotel. Then, take the rails to Fort Meade and stay overnight at the Fort Meade Hotel, the closest stay-over to the depot. Finally, one could hitch a ride with the mail messenger to Pabor Lake the following day. At Avon Park, prospective settlers could lodge at the Hotel Verona (given that no temporary lodging was available within the colony). It wasn’t exactly the most accessible destination!

The single greatest desire shared by ridge communities was a railroad. In addition to Avon Park and Pabor Lake, numerous small settlements had sprung up nearby, including Midland, Lake Buffum, Buffalo Ford, Athens/Bereah, Arbuckle, Bee Branch, and Keystone City/Lakemont/Frostproof. Locals envisioned a line running along the ridge, connecting these isolated towns to the outside world via Haines City.

The rail was the lifeblood of development. Not only did it make it easier to bring new settlers and visitors in, but it could easily cut the time and price of shipping products (both in and out) by a third or more. The steel road opened up entirely new markets and new types of crops that could be grown. In the era before refrigeration was common, many crops, such as vegetables, would long spoil before they could ever reach their destination to be sold. The rails would be a game-changer.

In October 1892, the founders of several towns formed a company and began soliciting investment to build the “Frost Proof Line” from Haines City to Avon Park with stops at Crooked Lake, Midland, and Pabor Lake. The group eventually planned to extend the route south to a port at either Punta Gorda or Fort Myers.

By April 1893, William E. Pabor successfully lobbied his many contacts to get Pabor Lake, FL, added to most of the national railroad maps. This not only gave the town additional visibility and aided in navigation, but Pabor hoped it would help blaze the path for the coming rail line.

Despite their best intentions, the company and its successors faced variable bouts of progress and setbacks in completing their mission. The township would not be connected by rail to the broader world until too late for the Pabor Lake Colony. The Atlantic Coast Railway did not finally reach Avon Park until 1911.

No Post on Sundays

In January 1893, the little hamlet of Pabor Lake petitioned the United States Postal Service for an outpost of its very own. Though only a tenth its size, the Pabor Lake Pineapple claimed that one-third of the mail going in-and-out Avon Park’s post office was from the colony. This was almost assuredly true, given the large inflows and outflows created once a month by the popular pink newspaper itself and related correspondence.

Regardless, enough signatures were executed, so the postal service accepted the request. On April 10, 1893, the post office at Pabor Lake, FL, opened for business in the first structure at the town site’s main intersection at Lake and Central.

In June, the building was upgraded to include the contemporary riggings of a rural post office. W.E. Pabor himself served as its original postmaster—for the second time in his life, holding that title (previously held in Harlem as a much younger man). His son, Charles, served as its mail carrier.

(The post office) consists of a counter cabinet, containing eighty-four call boxes and all modern conveniences for handling the mails. In addition we have ordered a Victor Safe.

Pabor Lake Pineapple — June 1893

At first, mail was routed out of Fort Meade, but by the late summer of 1893, the Avon Park and Pabor Lake train and mail service shifted to Bowling Green. This made for some happy folks locally; they enjoyed it as much for supporting another DeSoto County town (Fort Meade was in Polk County) as they did for being rid of adversarial Fort Meade as their connection to the outside world.

The Pabor Lake post office would double as a small, ill-supplied general store for the town. Pabor remained postmaster for several years before handing the duties over to another settler (perhaps Charles). The office remained open until 1900.

A Turkey Named Tom

Every town needs a mascot, and Pabor Lake had a right-friendly one by the name of Tom. The family ordered a live turkey from Fort Meade to be delivered in time for Thanksgiving Sunday dinner. They would slaughter and serve the bird to give them a much-needed reprieve from the canned meats on which they had been largely sustained for weeks.

However, the turkey arrived late. When the next Sunday dinner approached, Emma “Florabelle” Pabor had decided she had become too friendly with the bird, giving him the name “Tom” days ago.

Tom became well-known across the settlement. The plumed pet would play with the kids and follow the family around the seven lakes as they did their daily business. He would welcome any new visitors to the area with a resounding “gobble” and would disappear from time to time as he ventured out to visit with neighbors on Lake Damon or Trout Lake.

Each night, he returned home to roost in the stable’s rafters on Pansy Lake, near the Cosy Cottage. He was a fixture for the next two years at all town events until Tom passed in July 1894. The family wept legitimate tears and conducted a sincere funeral, complete with flowers and a casket. They laid him to rest along the banks of his Pansy Lake home.

Inaugural Founders Day Celebration

The town’s one-year anniversary had suddenly arrived, and in many regards, things were going swimmingly. So well, in fact, that the colony lands were expanded westward to include the western banks of Lake Vigo (Adelaide) near what is now the Avon Park Lakes subdivision. Plans were made to acquire additional acreage west of Pabor Lake, and additional villa lots were opened for sale around the circumference of Pabor Lake (whereas previously, only lots on the southern shore had been offered).

However, all was not perfect. After all of the dozens of property sales by that time, the only families taking permanent residence at the one-year mark were the Pabors, H.G. Burnet, John DeHoff, Otto Hahn, and Hadley.

Life on the frontier was not an easy one. With no modern conveniences, a leaky roof, the Florida heat, too many bugs, and a still mostly unadorned cabin, Emma Pabor was ready for a break! After six months in the colony, she left with ten-year-old Pansy to spend the next eight months in Colorado. The ladies of the household would finally return for good in January 1894, once their Cosy Cottage had some much-needed repairs and could be afforded with carpet, curtains, and pictures on the wall.

Despite Emma and Pansy’s absence, a grand anniversary celebration was held on July 18, 1893. The town’s park was triangular in shape, with its northern boundary following the southern banks of the town’s namesake lake and stretching eastward from its western apex toward Trout Lake and Pansy Lake. Its picnic grounds were anchored by the stately 250-year-old oak trees known as Twin Oaks, which were admired by all.

Welcomed by the perks from Postmaster Kinney’s coffee kettle, folks began to pour into Pabor Lake bright and early. They came from surrounding towns such as Avon Park, Frostproof, Midland, and even as far away as Fort Myers and Jacksonville. Carriages toured the visitors around the hamlet, as it was the first visit for most guests.

A basket lunch was held under the Twin Oaks, providing a much-needed retreat from temperatures that climbed into the 90s by noon. Formal festivities for the bash kicked off at 1 p.m. The women of Pabor Lake (minus Emma Pabor) played host by setting up tables and a large spread of food. Lemonade was a cool favorite, with ice from Bartow and limes supplied by William King’s Grove in Avon Park.

Following Reverend Gale’s blessing of the meal, the ninety guests feasted and socialized for hours. The kids enjoyed the swings, swimming, and climbing the oak trees. Area singers and musicians performed live music.

At 4PM, there was a flag-raising ceremony with a huge star-spangled banner (8 feet by 15 feet) that was donated in absentia by the yet unsettled land owners. Pabor and others spoke about the year it had been and the bright future yet ahead. Letters were read aloud from others who could not be there in person before the group posed for photos.

Guests picked over the leftover food as the sun started to settle in the west, and Pabor called for a swimming contest across Pansy Lake, with the winners receiving a free town lot! Once darkness arrived, fireworks soared over the lake. While the children and older folks retired home, the young people danced until midnight in the post office building. What a time they had! And all looked forward to the sequel in 1894.

Year Two

Things continued to progress slowly for the community. New families moved in, primarily settling along lakes Damon, Pansy, Trout, and Pabor. The town’s founder found himself so busy that he began to employ another settler (Otto Hahn) to manage his gardens and grove.

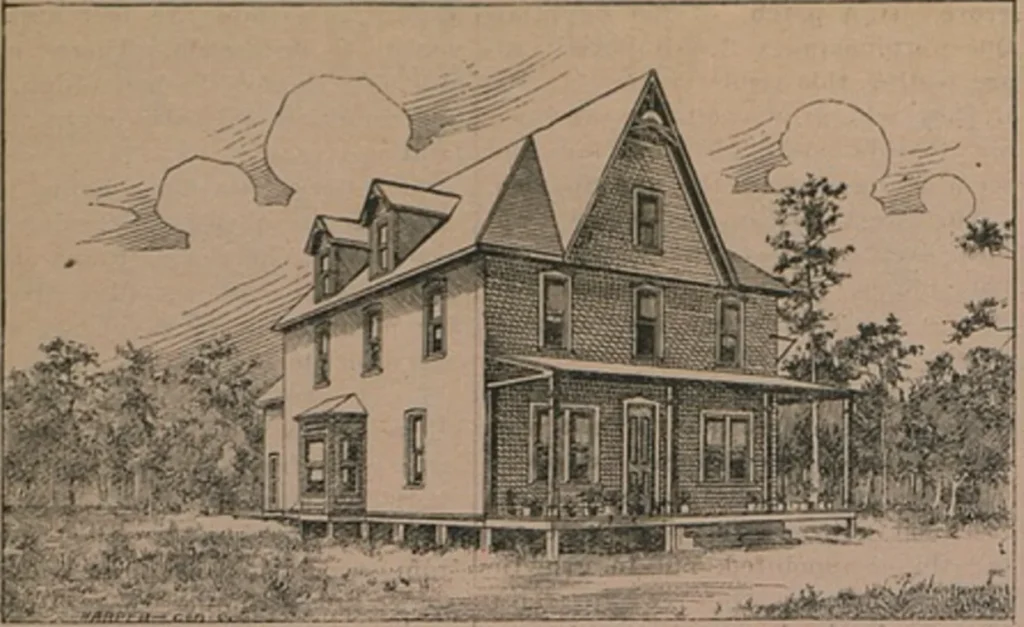

With the Cosy Cottage now up to Emma Pabor’s standards, attention turned toward building a hotel. While they dreamed of a grand lodge called the Wayside Inn on the southern shores of picturesque Pabor Lake, the practicality of such an expensive venture required it be put on hold, they decided, until the railroad from Haines City arrived.

So, instead, they constructed a smaller structure in the town’s center. It was two stories, 30-feet by 38-feet, and catty-corner from the post office. The first floor housed a dining room, pantry, office, parlor, and parlor bedroom; the second had six bedrooms, allowing guests and new settlers to conveniently stay within the colony until their cabins could be completed.

Pineapple slips were said to take between 18 and 24 months to produce a harvest, so the townspeople anxiously waited for their growing plants to soon blossom. They hoped they would do so in time to fill the 150,000 they had contracted.

Meanwhile, the settlers tried many other types of crops, some with great success while most were complete failures. But they learned from each. The ten separate garden parcels around Cosy Cottage of the Pabors were created for various planting experiments. And many considered it a pleasure to tour the sprawling landscape there.

As the spring wound down, the seeds of a year-long teenage romance were coming to blossom. Jessie Kinney, the postmaster’s daughter from Avon Park, had started a well-known relationship with Charlie Pabor on July’s Founders Day. During most of that afternoon’s activities, the two stole away on a small boat in the middle of Pansy Lake, doing what one might expect teenage boaters in love to do. On May 9, 1894, the two were married at the Avon Park home of the Kinney family, attended by Reverend F. N. Barlow.

Second Anniversary Celebration

Another year had zipped by in what seemed like no time at all. The growing group of residents was once again joined by a large contingent of guests from Avon Park, along with visitors from Bartow, Frostproof, and Athens (Bereah). Since the patriarch had been away for weeks due to his duties with the National Editorial Association, his sons, curly-haired Charlie and William H. Pabor, administered all of the planning for the second annual.

The Twin Oaks Park at Pabor Lake once again served as the hub for recreation, with adults gossiping on newly installed park benches while supervising their swinging children. Local hunting guide C.L. Farnham of Avon Park provided a rare and particularly well-received treat for the steamy summer morning: ice cream!

With rain clouds looking threatening over the horizon, the Welcome Inn served as the center for formal presentations and dining this year. At 11:00, the group gathered at the newly constructed hotel. A group of area leaders, including Avon Park founder Oliver Crosby, addressed the crowd from the front porch stoop about the struggles of founding and the hope for the future. All agreed on the important interlinking destinies of the sister towns of Avon Park and Pabor Lake.

Inside the hotel, guests found a large dining table spanning the entire 38-foot length of the building, festooned with an abundant lunch spread. After lunch, a contingent of gentlemen left immediately to make it to Fort Meade by evening and then to Arcadia by train for an immigration and railroad meeting. For the rest, afternoon activities continued.

Over the past year, a beach of over 100 yards had been cleared along the south shore of Pabor Lake, and it proved a well-received destination. In addition to the second annual 600-yard swimming competition (won by S.E. Walsh), Paul Krause won a 100-yard foot race down the sandy beach. Appealing for equal treatment in this early era of the women’s suffrage movement, the young ladies demanded their own race. Allie Woodruff won the 100-foot female heat against three other competitors. All three winners claimed their prize of a free town lot.

As the sun faded into the distant horizon, fireworks lit the sky. A light evening meal was served, and music and dancing into the night at the Welcome Inn. Another fine celebration!

Pineapple Problems: Pabor’s Puzzle Leads to Drama

As the heat of the summer started to give way to cool fall breezes, William E. Pabor started to get worried. He noticed that while thousands of pineapple plants had grown up strong, healthy, and producing suckers (which are side shoots), few were actually looking as if they would produce any fruit this season.

This revelation was particularly troublesome due to the 150,000 orders they already had contracted to fill! The assumptions of the pineapple’s 18–24 months to mature harvest were based on many accounts in agricultural publications at the time. So Pabor began to wonder: Were these accounts incorrect? Was the soil in the colony not conducive to producing fruit as quickly? Or was there another reason the Avon Park township had not garnered a harvest as successfully as promised?

These concerns were expressed in a letter to the editor on October 13, 1894, in the Florida Farmer and Fruit Grower newspaper. Almost immediately, it set off a firestorm of responses in this and other publications all the way through Christmas. Some answered his “puzzle” with profound theories and observations; others from rival growing regions scoffed and joked. At the same time, locals of neighboring Avon Park (especially William King) fumed at what they viewed as tarnishing the region’s growing reputation.

The Great Freeze of 1894–1895

There were no indications of what was to come. The fall gave no omens of the destruction that would soon follow. Christmas day rolled around in Central Florida with beautiful weather and temperatures in the 80s. Hope sprung eternal among area farmers.

On December 28th, a violent cold front rolled through the state, bringing storms and high winds. What followed on the other side was nothing short of disastrous. Black Friday, as it was referred to, sent the mercury dipping to 22 degrees in the Pabor Lake Colony. The next day, residents arose to survey the devastation.

Pineapples, bananas, tomatoes, and countless other crops had been decimated, causing near-complete crop failure, representing essentially two years’ effort. The settlers grieved the loss of their “frost proof region,” as nature forced them to eat their boastful words and over-blown claims on a bitter plate. The “frost line,” some said, now rested around the Florida Keys.

But some solace was found. After having cut away the brown and dead upper sections, green life was encountered within the heart of the plants. A warm January brought further hope to the farmers, as the plants quickly began to burst forth with new growth and restored color to leaves. While the season was lost, perhaps a small late-year crop could be salvaged!

Then it happened again. On February 7, 1895, another arctic blast walloped Florida, sending warm afternoon temperatures plummeting into the freezing range. Among the seven lakes and the Avon Park township, temperatures got as cold as 23 degrees and stayed below freezing for the next two days.

The carnage from the second round of the Great Freeze was even worse than the first. While no fruit was left to be destroyed, the mature insulating foliage was also gone. In its place were tender shoots of new growth, fostered by the 80-degree temperatures throughout January, thus leaving the trees and plants more vulnerable than before.

Some witnesses report what sounded like pistol shots as the abundance of new sap flowing within the trees froze and then violently burst the wood from within. Most of the crops were killed to the ground, at best leaving the root system as the only surviving section.

Attempts at Recovery

In the coming months, most at the Pabor Lake Colony tried to save the plants by nurturing the root system in attempts to regrow rather than replant. Time would later teach them that a better strategy might have been to start over completely from new plantings, as many regions saw a quicker rebound with that strategy. But hindsight is 20–20, isn’t it?

Many other crops were tried that they hoped would prove better suited to the new reality of Florida weather: the now all-too-regular freezes in the formerly frost-proof region. They tried Jamaican sorrel, varieties of apples, peaches, Suriname cherries, figs, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, eggplants, coconut palms, and countless others.

Some of the new crops proved successful but not necessarily commercially viable. Smaller pineapple harvests finally followed in 1896 and 1897, with about 100 acres of the fruit grown in the Avon Park-Pabor Lake area.

Oranges, lemons, pomelos, and other citrus eventually returned to the region (seedling to harvest is about 5–7 years for orange trees). But time would prove to be the biggest enemy, as many Northern settlers—having lost life savings in some cases—eventually retreated back home, giving up their Florida pioneer dreams.

Nurseryman and Pabor Lake’s second settler, H.G. Burnet, toughed it out until the spring of 1896. After another (much more minor) frost that winter, Burnet had had enough of Florida. He packed up his family and moved to Jamaica, where he figured the frost could not reach him even in the coldest winter blasts!

Another Anniversary

In March 1895, another son was married. William Helme Pabor married Vernie Taylor of Denver. The two settled into a villa home along the southern shore of Pabor Lake.

Vernie fit right into her new pioneer home, assisting Emma Pabor and Mrs. John DeHoff in serving the third annual Founders Day lunch under the Twin Oaks at noon. This year’s turnout was smaller than the past, with only around 50 guests in attendance, but they still greeted visitors from Avon Park, Midland, Ft. Meade, Frostproof, and other local settlements.

Photos were taken of the group at Pabor Lake beach and around the colony. The group moved to the porch of the Welcome Inn for the traditional round of speakers and then dinner at 6PM. The institution of swimming and foot races was apparently retired, possibly since unsold town lots were in short supply by then (actual town settlers were also still in short supply).

After sunset, a full 85-piece fireworks show rocketed through the sky. The kids took charge of the hotel dining room thereafter, with lemonade and cake to fuel them onward. They danced until midnight once again.

“All Aboard!”

Settlers of the Lake Wales Ridge region were super frustrated by the summer of 1895. They had been seeking investors and companies to assist with completing a Haines City-to-Avon-Park railroad line for three years. There had been many instances where reports said the line was imminent, only to have something or other come up to cause cancelation or delay. The freeze did nothing to help ease the minds of prospective investors of a railway to the now not-so-frost-proof lake region.

The Avon Park Transportation Company, as it was called, had finally had enough. They would do it themselves if no one else would construct the rail! Though they did not have the funding for the steel railway they desired (which was necessary to support full-sized trains capable of connecting the national network), they decided to commence construction of a wooden “tramway” capable of transporting smaller railcars as a connection to the steel-track depot — most likely at Bartow.

This wooden railway was a true innovation and tribute to John C. Burleigh’s ingenuity. Initially, the tramway was conceived to move timber for his sawmill on Lake Thompson (Brentwood) in Avon Park.

It proved such an affordable and effective method in his commercial enterprise that the Avon Park Transportation Company was convinced it should extend the spur to connect settlements throughout the ridge. By summer’s end, the first segment of the tramway was completed between Avon Park and Pabor Lake Colony.

One of the most remarkable railroad lines in the world is what is known as the Frost-proof Line, that is now completed from Avon Park to Pabor Lake, Fla., and consists of wooden rails, fastened together with wooden strips, held by wooden pins. It is laid along the surface of the ground and ballasted with sand.

New York Railroad Men — October 1896

The tramway tracks’ original path followed the modern railroad route. Its southern terminus was just south of Avon Parks’ Main Street (later extending southward to the Crate District). The tramway then traveled north past Burleigh’s former sawmill on Lake Brentwood, along the shores of Lake Damon, and parallels US 27 to the Cargill Juice Factory near the Polk County line. This is where the Pabor Lake depot was located—most likely never an actual train station building but just an unloading point.

On September 7, 1895, Avon Park’s first ceremonial steam engine reached Pabor Lake. Rolling into the station around 10AM, it unloaded around 100 enthusiastic guests from Avon Park. An hour later, the second train arrived with about 50 more individuals.

In all, 150 Avon Park residents (almost the entire population) joined the 40–50 residents of Pabor Lake and visitors who rode in from Frostproof and other localities. Together, they hosted the largest gathering in the settlement’s history, with over 200 people in attendance.

The group picnicked on the Twin Oaks park grounds, and then many exuberant speeches kicked off. Each speaker gave a round of back-slapping congratulations to the community members and officers of the Avon Park Transportation Company, who had made the day possible.

The one thing needful seems now to be coming, indeed, has come. Pabor Lake, in common with Avon Park, Frost Proof, Midland, Buffum, and other settlements north of us, will join in one grand celebration when the tramway, so happily reaching its first station, shall enter Bartow and touch the railway system of the State.

William E. Pabor

Finally, the band from Avon Park played one final performance, and the conductor yelled, “All aboard!” With a “toot toot,” the revelers were headed back southward toward Main Street. All felt confident of greater prosperity for the ridge communities in the coming year.

Calamity in Avon Park

As if the unrelenting setbacks from winter freezes and frosts had not been enough, an upheaval struck Avon Park and sent shock waves reverberating into Pabor Lake. In the middle of 1896, a flurry of lawsuits erupted, calling all of the land titles owned and sold by Oliver Crosby’s Florida Development Company into question.

Avon Park was in a panic. Residents rushed to the bank and struggled to maintain ownership of their properties.

Ultimately, Crosby was scorned by the townspeople and left Avon Park. Though he and his wife worked tirelessly to right the mess, he would not return to the city again for 25 years. Crosby was left virtually penniless as collectors auctioned off his personal holdings and that of the Florida Development Company.

The tainted reputation bled over to Pabor Lake. The November 1896 issue of the Pabor Lake Pineapple made it clear that the lands in the colony were not part of the controversy and had not been acquired from the Florida Development Company (but instead from the Kissimmee Land Company). However, for the time being, the damage was done. For many people, these events were the final straw in a long line of setbacks.

What Started with a Bang, Ends with a Fizzle

Financial burdens began to burden the colony and the Pabor family. By 1896, new sales were virtually nonexistent, so they struggled to make mortgage payments. The Welcome Inn was put up for sale at below cost.

The Pabor Lake Pineapple continued to be published in the colony through 1897. Despite some upbeat rhetoric in its pages, increasingly, issues began to indicate the winding down of the experiment.

Lots and even finished homes— possibly those who left town and stopped making payments to the Pabor family — were offered for sale at discounted rates in the paper. William E. Pabor himself began to invest increasing amounts of his time toward his prominent role with the National Editorial Association, which required his constant travel throughout the state and country.

The Association eventually built a headquarters and retreat home for its members in Interlachen, Florida. They called the private resort “The Editoria” and selected Pabor as its resident manager. This move marked the end of the Pabor Lake newspaper for the time being, and he would live separated from the family for the next two to three years, returning to visit them at the Cosy Cottage at Pabor Lake as often as possible.

William H. and Charlie Pabor took over the colony’s day-to-day operations as best they could. By the end of 1900, the National Editorial Association decided to close the Editoria, and the founder returned home to Pabor Lake—or what was left of it. Most of the colony’s settlers had given up and left town. Postal volume had dropped so low that the post office at Pabor Lake was closed in 1900 after seven years of operation.

The Crosby title crisis decimated the hopes of a railroad initiative crucial to the area’s further economic viability. The tramway plans never made it past Pabor Lake station, and no investors were yet in sight to connect to the township with steel rails.

Slowly, Avon Park began to bounce back, having 225 residents in the 1900 Census, and Pabor attempted to revive the Pabor Lake Colony concept. The Pabor Lake Pineapple was again published between 1903 and 1907, with circulation between 335 and 500 subscribers.

After so many years of winter setbacks, Pabor changed his tune about the virtues of growing pineapples out in the open in the Lake Wales Ridge region. Instead, the now 70-year-old extolled that pineapples could be profitably grown in the area under cover. Attempts to grow pineapples under manmade shelters had been tried — with mixed success — in more northerly parts of the state over the past decade.

Now, with no more viable claims of the area being naturally without frost (as is necessary for pineapple cultivation), this was essentially a Hail Mary to preserve the dream of the fruit’s commercial viability in Central Florida.

Advertisements for land sales within the colony can be found in many publications over the four-year period. These last-ditch attempts at resuscitating the Pabor Lake Colony in the 19th century produced absolutely no vital signs.

Gradually, even the Pabor family moved away, relocating to Avon Park and other parts of the state. The earth reclaimed the Cosy Cottage, Welcome Inn, post office, and the rest of the colony’s once proud roads and structures.

When the 1910 Census was taken, sixteen Pabors resided in the Avon Park township. But a year later, they lost their leader. While on one of his frequent trips to Colorado, visiting friends and his son Frank, the founder passed away. His funeral was held in Colorado and attended by some 5,000 mourners, including members of Congress.

Pabor Lake Today

No known manmade remnants of the colony remain today. According to Wesley Pabor, great-grandson of William E. Pabor, the cabin on Pabor Lake’s south shore that was once occupied by William H. Pabor and his wife Vernie stood—if barely—in a state of disrepair into the 1990s. The property was set ablaze in a controlled burn and used for a training exercise by the Avon Park Fire Department.

The total size of the former Pabor property was quite expansive (over three square miles). Still, the footprint of the once-settled portion of the Colony lies east of the railroad track along the right side of US Highway 27 North, between Lake Damon and the Polk County Line. No settlers built north of the county line or anywhere east of River Greens golf course. The northern shore of Lake Damon marks the southern end of the colony’s populated realm.

The entire area, once the “downtown Pabor Lake,” referred to as the “town site” on the old plat maps, is now entirely covered by orange groves. (If any orange trees are left there after a few years, given the contemporary problems with greening disease)

Colony lands on Trout Lake, near the old homesteads of settlers N. T. Plummer and John DeHoff, are now part of Camp Wingmann. In 1939, John Sears Francis donated this summer camp and retreat facility of the Episcopalian Church to the religious order for that purpose. After a couple of decades of changing hands and purposes between the 1970s and 1990s, today, it once again operates as a summer camp for the Diocese of the Episcopal Church.

River Greens Golf Course now encompasses the land between Lake Damon and Trout Lake. This area long served as the heart of the colony, where most residents resided. Most notably, the founder’s home (and cabin known as the “Cosy Cottage”) rested on about ten acres between Pansy Lake and Lake Damon. River Greens, along with the Casa del Lago subdivision, probably also encompassed the homesteads of the Burnet, Hadley, Hahn, and DeHavens families (and perhaps others).

Some of the palm trees now found on Pansy Lake’s south shore may well be descendants of those introduced initially by the Pabor family. With ground penetrating radar, grave sites of Tom the turkey, Major the dog, and Harriett Helme (87-year-old mother of Emma Pabor, who died on April 17, 1896) would likely be found along its southern banks.

A nine-hole golf course operated on the property during the middle of the century before it went defunct. Rodney Davis moved to Avon Park in 1969 and purchased the course with his father, John, and brother George. They renamed it River Greens after a course by the same name that they owned in Ohio.

After revitalizing the facility, they added another nine holes in 1972. Today, the Davis family still owns the business and continues to thrive. Hundreds of residents reside there.

Things did not go according to William Pabor’s well-laid plans and specifications. However, with his beloved Seven Lakes region now occupied with agriculture, beautiful homes, happy residents, plenty of green space, and recreation… perhaps the founder would be pleased at what it has become. Maybe the Pabor Lake Colony is not so lost after all!

References

Most of my research material came from William Pabor’s own words in the Pabor Lake Pineapple. The issues from 1892–1897 are available online:

http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00020306/00001

Full research notes and links: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1OMOiO7yc0T8nDori0y2A4wR5UY0-7zlHyrbDJnWj820/edit?usp=sharing

Estimated map of the Pabor Lake Colony with landmarks:

https://www.google.com/maps/@27.6430614,-81.5228048,4148m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m2!6m1!1szbibjWJDhAvU.ksmaK2ggRv6A

Thank you to Wesley Pabor (the founder’s great-grandson) and Amber Davis White (the daughter of the River Greens Golf Course owners) for their time and for allowing me to ask them questions.

This post is 3626 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.