Southern States Feared Negro Domination

Nothing was more terrifying to wealthy landowners in the post-Confederate South than an empowered black electorate. The suffrage of the previously subjugated class could easily disrupt their monopoly on Southern politics.

The 15th Amendment, in theory, guaranteed the right to vote for all male citizens over the age of 21. Upon its ratification in 1870, the black population of the South numbered nearly five million. That number would increase to around ten million by 1910.

In a few states — such as South Carolina — this gave newly-minted black citizens the clear majority. In others, the powerful minority represented between 20 and 50 percent of potential state voters. As freed slaves migrated from plantations into cities, the white elite in municipalities like Jacksonville foresaw their grip on the local level slipping from their fingertips.

There was little that they could do about it during the Reconstruction era. Union forces still occupied much of the South and enforced the 14th Amendment, ensuring equal rights under the law. In a short time, many blacks rose to significant influence and held political office.

However, after the backroom deal known as the Compromise of 1877, Union troops withdrew, and all bets were off. Without the Yankees to secure black rights, the power vacuum allowed incensed whites to take back what they felt had been wrongfully taken from them. And betrayed blacks would pay dearly.

At the time, most Southern whites were members of the then-conservative Democratic party. However, a small but growing number supported the more progressive agenda of Abraham Lincoln’s Republican party — including many working-class whites and immigrants from the North. Virtually one hundred percent of blacks were aligned with Republicans.

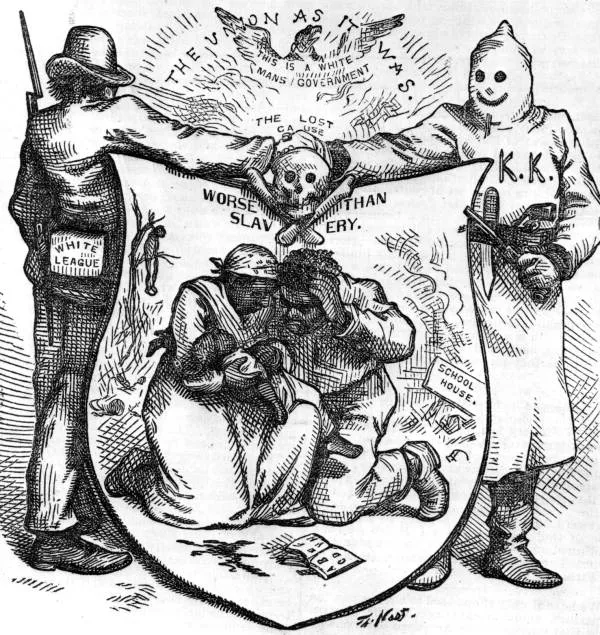

Simple math showed that enfranchised blacks (plus the white Republicans) could override the will of the white majority. Newspapers spoke out with inflammatory warnings against this effect, calling it “Negro Domination.” It was a clear threat to the white monopoly of Southern commerce and politics — from the local level on up to the presidency.

Therefore, it was paramount that “negroes” be kept ignorant of their great potential. Without the Union troops, white elites were allowed the unchecked authority to implement repressive laws and voting requirements.

These Democrats were known as the “Redeemers.” Their sole goal was to restore the complete supremacy of wealthy white landowners. And they would be brutally successful in this task.

Tactics like poll taxes, literacy tests, violence, and intimidation are well-known methods to keep blacks from voting. Other techniques, such as subjective understanding tests, white-only primary participation, good character requirements, and educational requirements were practiced. Poor whites were sometimes exempted through grandfather clauses, which essentially granted them voting rights if their grandfather could vote.

Even many decades later, violent means were employed when necessary to assert this position. These brutal methods of suppressing the black electorate culminated at times into essentially localized genocide, such as in the Ocoee Election Day Massacre of 1920.

The criminal justice system was a vital vehicle for this repression. The Constitution included language guaranteeing voting rights “except for participation in rebellion, or other crime.” This left the door wide open for selective or creative enforcement of the law and an anything-but-fair justice system.

Crimes entirely manufactured or as simple as gambling on a dice game could easily mean conviction, incessant debt, and loss of voting rights. Law enforcement offered blacks neither equal protection nor equal enforcement under the law and served mainly as an instrument of white supremacy.

For the next eighty years, this systematic oppression was rinsed and repeated over and over again. From time to time, one discriminatory method or another would be deemed illegal by a court or Congress, yet that only meant it would morph into another form to essentially the same end.

Not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were most of the practices finally reduced to barbaric relics of the past. Yet while we are in an infinitely better place than in those dark times, some of these techniques have not been put to rest. No, they have simply morphed again.

Today these practices manifest themselves in gerrymandered voting districts, inconvenient or under-staffing polling locations, restrictive voter registration windows or requiring government IDs, intimidation, or misinformation. And — yes — American oppression’s primary tool still reigns: the machine of the criminal justice industrial complex.