Orlando’s Fort Gatlin and Council Oak

Historians have debated the location of the fabled landmark where Seminoles gathered. Let’s solve the puzzle.

Background: Orange County was Seminole Territory

Contrary to popular belief, the Seminoles were not natives of the Everglades. They didn’t even have a unified identity until much later. One by one, the independent groups migrated south; they arrived as refugees. The displaced bands — largely of Muskogean-Creek origin — found a haven in the mostly uninhabited wilderness. Florida’s original natives were gone, having died (whether by war or disease) or fled to Cuba by the mid-1700s.

Outside Pensacola and Jacksonville, the population was almost nil. Small tribes fled oppressive Englishmen to settle in the Panhandle and northern Florida. Despite the American invasion of Spanish Florida during the First Seminole War (1817–1818), they thrived in their new home.

In 1821 the United States took possession of La Florida, and within months the clash began anew. The U.S. motivations were not simply craving land. They also sought a buffer zone between the Seminoles and plantations in Alabama and Georgia. Seminole camps were a beacon for runaway slaves, who often fled southward and either integrated into or lived in separate but affiliated communities to the Seminole clans.

In 1823 the Treaty of Moultrie Creek was signed near St. Augustine. The Seminoles agreed to abandon their lands in northern Florida (except for a few outposts near the Apalachicola River). The United States promised compensation and a four-million-acre reservation stretching the territory’s interior from Ocala to Polk County — carefully excluding the coastline.

Before the ink could dry, white settlers resumed the incursion into Seminole land. Americans had no intention of honoring the negotiated boundaries or its other commitments. Military officials pressed tribal leaders to abandon their claims and relocate to the Great Plains. The natives were pushed further south until, decades later, only a few hundred holdouts were left in the Everglades.

When Andrew Jackson became President in 1829, the writing was on the wall. The cruel leader, who was the general during the First Seminole War, was fixated on removing them. One of his first acts as president was signing the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

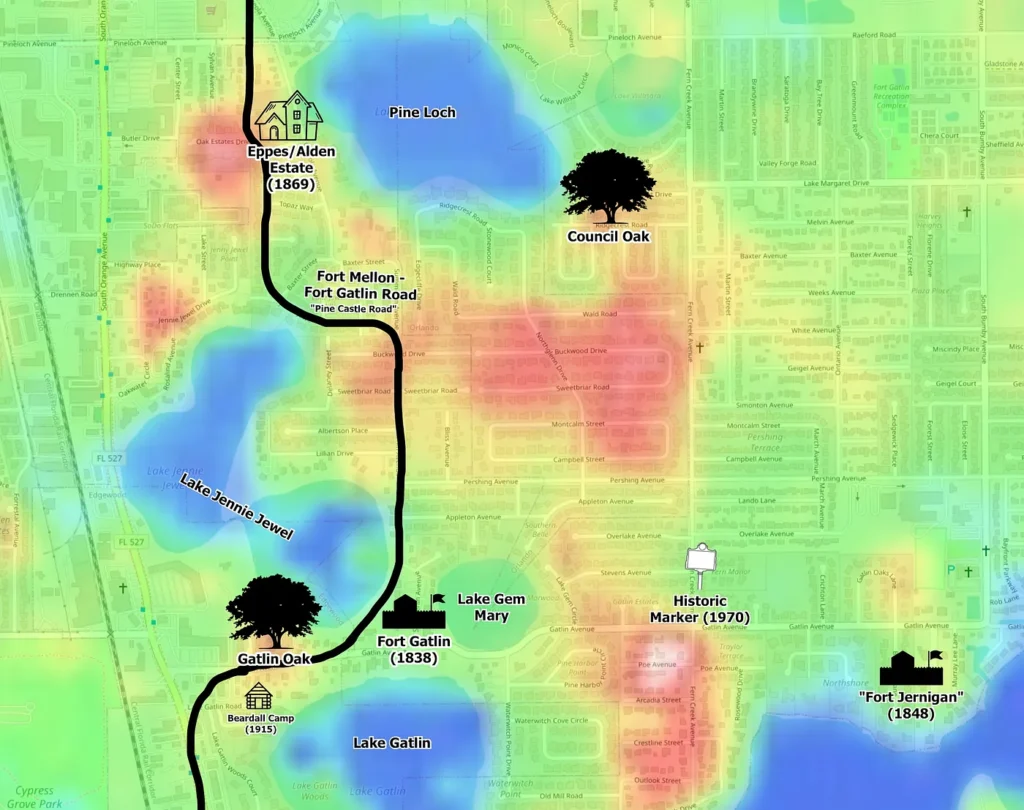

After it became clear the Seminoles were not in the mood for surrender, Fort Mellon was constructed at Lake Monroe in 1835. It was one of the first outposts of the Second Seminole War. Fort Maitland and Fort Gatlin were added in 1838. A military trail running south from Sanford linked them before eventually arriving at Fort Brooke in Tampa.

Orlando’s Fort Gatlin

The garrisons along the trail were each about a day’s walk apart. The crude structures had pine fencing 15 feet high, peek holes every eight feet, and a two-story blockhouse on two corners. The entire fortress was often no more than an 80-foot wide square.

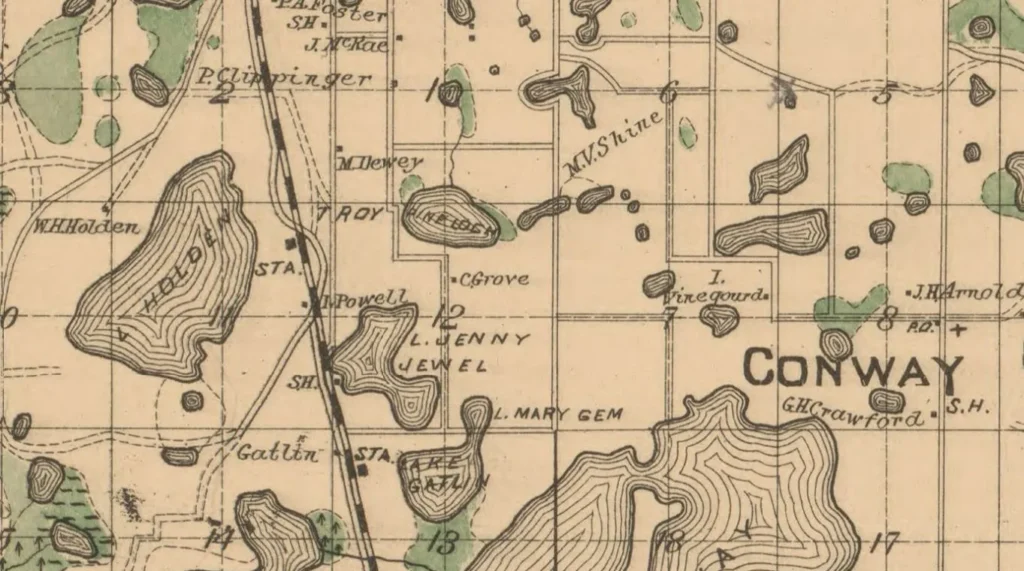

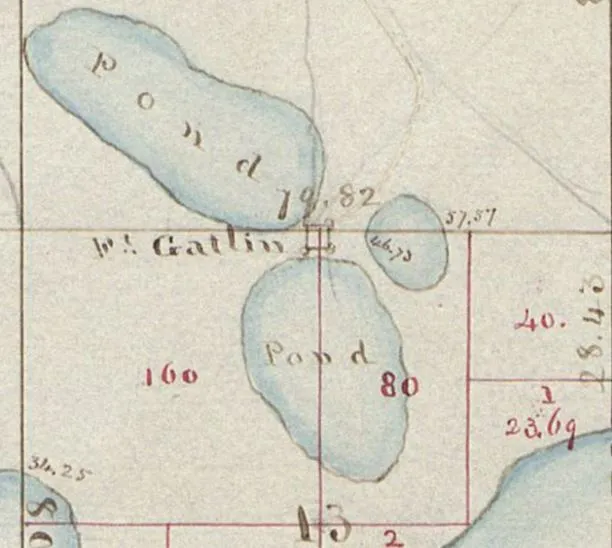

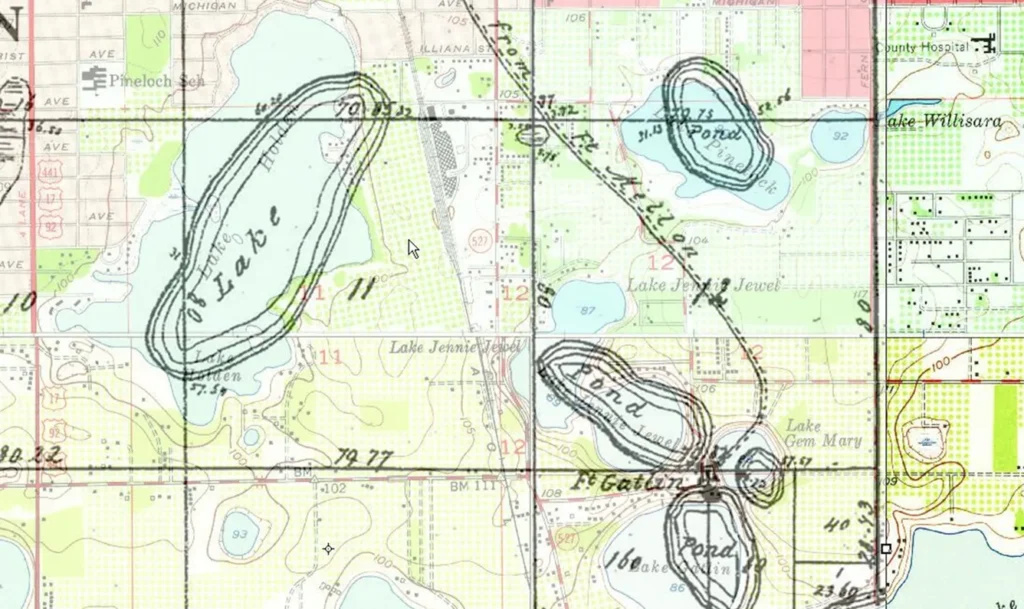

Fort Gatlin was built in November 1838. Its location was carefully chosen at a point between three lakes: Jennie Jewel, Gem Mary, and Gatlin. The lakes allowed for three chokepoints for defense and visibility of incoming attacks.

The federal government found the Seminoles fierce and grew weary of the high cost of the war. President John Tyler decided to effectively enlist citizens as soldiers. The Armed Occupation Act of 1842 incentivized white settlement in the Seminole’s territory. It granted 160 acres to farmers who would build a house, cultivate the land, and defend it for at least five years.

Aaron Jernigan jumped at the offer; he was the first grant in what is now Orange County. He moved his family from Georgia, near the Okefenokee Swamp, to the shores of Lake Holden in 1843. It was just two miles northwest of Fort Gatlin, which had been decommissioned by that time.

Run-ins with the Seminoles were frequent. Although the tribesmen’s animosity toward their new neighbors is understandable, many of the skirmishes were incited by whites. Jernigan, in particular, had a reputation that included theft of Seminole livestock, fraud, cruelty, and even murder. He was named captain of the rag-tag Central Florida militia to battle the natives.

Between 1848 and 1849, the confrontations escalated substantially. Jernigan constructed a new settler’s fort on the northern shore of Little Lake Conway, a mile east of Fort Gatlin. For more than a year, all of the area’s settlers abandoned their homes and hunkered down in the makeshift fort. The US sent troops to repopulate Fort Gatlin, and the attacks eventually subsided.

The Legend of Council Oak

A heavily forested ridge was between the old fort and Lake Pine Loch to the north. The old road wound its way through the woodland northward from Fort Gatlin and swept to the west of Lake Pine Loch.

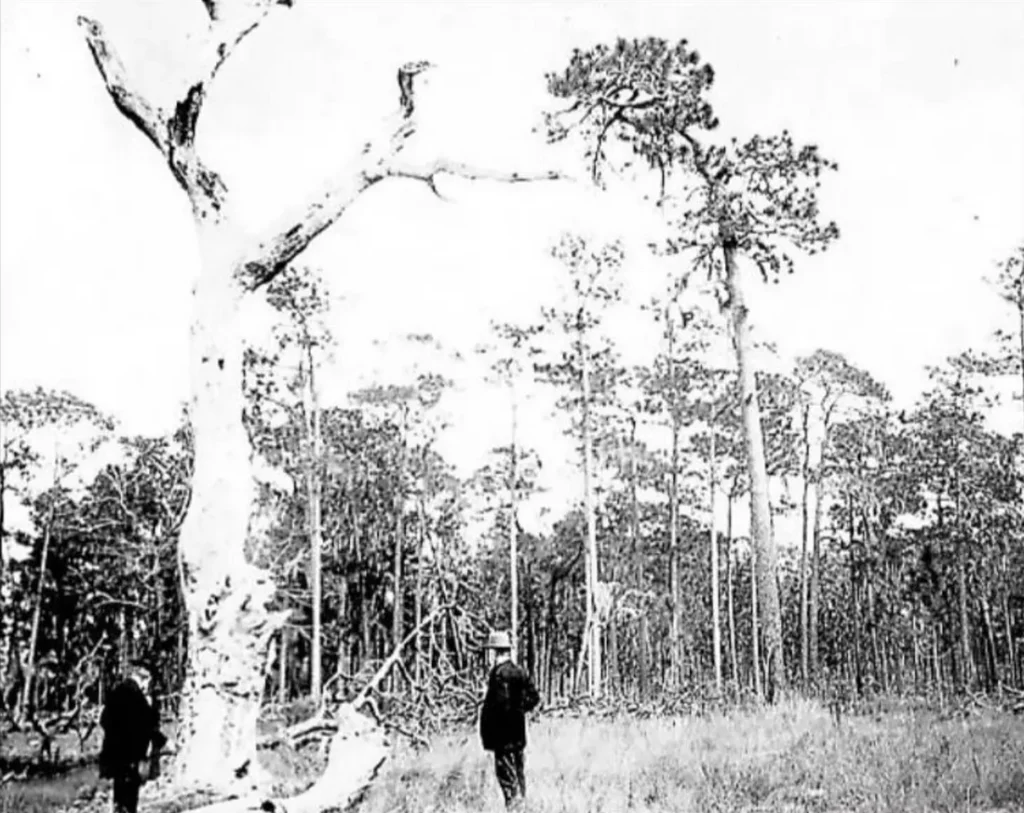

Among the many large oaks along the ridge, the most legendary was known as Council Oak. Its limbs were said to stretch out for over an acre. It watched over the untamed jungle for centuries, serving as a waymarker for Native Americans and pioneers.

Under its branches, tribal leaders held summits. Legend has it Osceola, Micanopy, and other Seminole chiefs met here to strategize surprise attacks at the Battle of Withlacoochee and Dade Massacre of 1835. In later years they planned offensives against Fort Gatlin and Captain Jernigan’s militia.

After their eventual defeat, Seminole chiefs reportedly met with US military officials under a large live oak near Fort Gatlin. At the tree, some clans tearfully negotiated their removal to Oklahoma, while others refused to surrender.

The Council Oak mourned the deportation of its friends, who held the mammoth hardwood in almost religious esteem. In the decades that followed, the anachronistic giant stubbornly persisted as the silence of its landscape was increasingly interrupted.

After the embers of the Civil War died down, a flood of new homesteaders poured into southern Orange County. In 1868, two famous settlers moved into the neighborhood of the great oak.

Beloved American poet William Wallace Harney’s built a large cabin timbered from the area’s plentiful pines. The home sat along the north shore of Lake Conway to Council Oak’s south. The Harney lodge was aptly called the “Pine Castle,” eventually lending its name to the entire community.

To the north, wealthy Virginia native and Tallahassee plantation owner Francis Wayles Eppes built his large estate on the west side of Pine Loch. Eppes spent much of his childhood living at Monticello with his grandfather, President Thomas Jefferson. The home is heavily modified but still exists.

The Mystery: Where was Council Oak?

Despite the fame of the tree that was once reportedly the largest live oak in the State of Florida, information conflicts about its exact location. Some say it was on the west side of Pine Loch, others on the east. A few writings place it along the military trail near Fort Gatlin, while others indicate it was further away from the fortress.

I’ll attempt, as best I can, to weigh the validity of the sources and hopefully put the mystery to rest.

South Ferncreek and Gatlin Avenue?

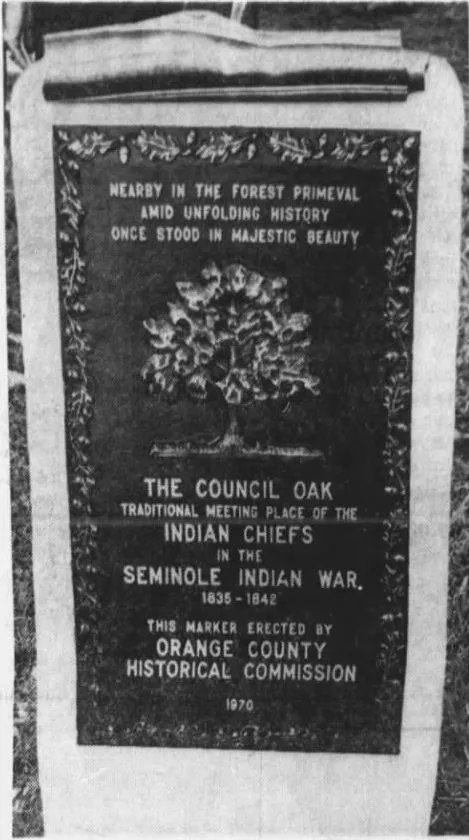

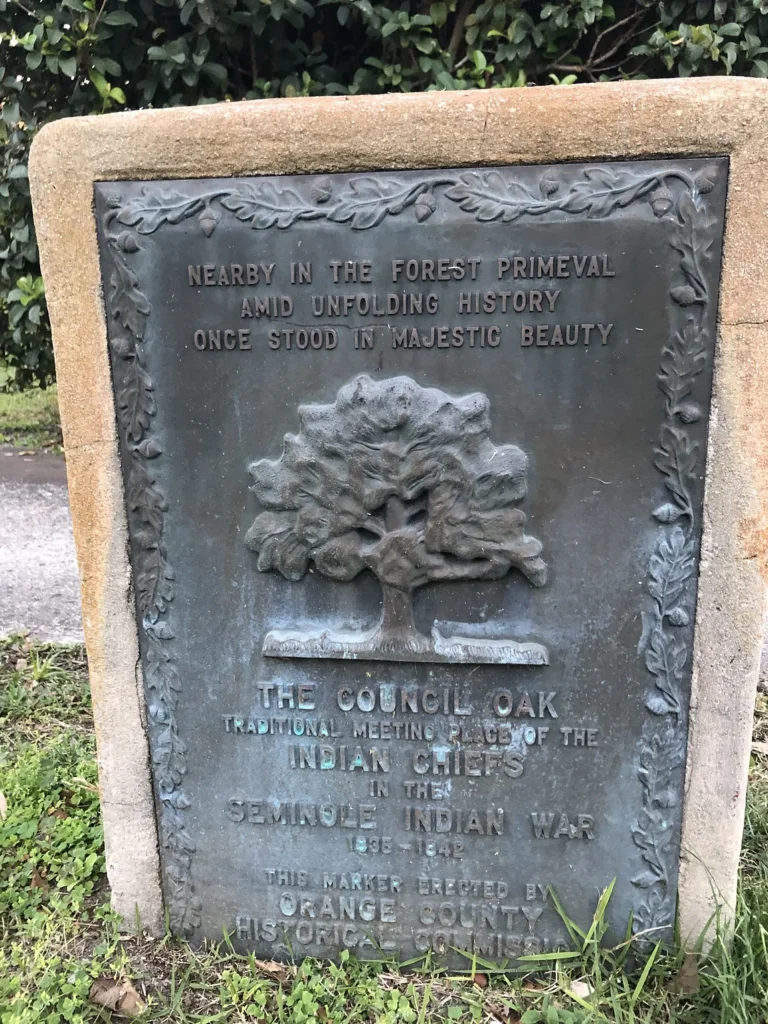

The Orange County Historical Commission placed a marker to commemorate the Council Oak in August 1970. It is unassumingly located behind a mailbox along South Fernceek Avenue, just north of Gatlin Avenue. Does this indicate the tree’s exact location?

The placard seems vaguely worded that the tree was “nearby,” rather than anything more definitive. It is unclear how the location was decided upon, but no other supporting evidence places it specifically at this point.

The marker is located half a mile east of Fort Gatlin. By walking distance, it is closer to three-quarters of a mile away on the opposite side of Lake Gem Mary.

At Fort Gatlin Theory

In the 1915 book Early Settlers of Orange County, Annie Caldwell Whitner placed the tree “at Fort Gatlin.” Adding it was then still existing as a ghost, saying there “stands the bleached trunk and bare widespread branches of an immense dead live-oak. It is said that, under this oak, the red men and white met to hold a council.”

Backing up the “near the fort” hypothesis, Martha Tyler Jernigan was present at the dedication of the Fort Gatlin marker in 1924. She was the daughter of Captain Jernigan and, at 85 years old, the last survivor of the group who spent a year inside the settler’s fort in 1849.

The Orlando Sentinel reported that “on the day of the unveiling (Martha) told several interesting reminiscences, pointing out old Council Oak and the place where the stockade was placed.”

This would lead us to believe it was close enough for the 85-year-old to walk to and point out its location. The description seems to indicate it was still present at that time. The marker is located on the corner of Summerlin and Gatlin avenues.

Then in 1925, the Orlando Sentinel mentioned that the tree’s dead branches were still visible. It said, “a council was held beneath one of the large oak trees near the fort at which time the Indians received the ultimatum… that ships awaited them at Tampa to carry them to their home on the Indian Reservations of the West. …The massive oak seems to mourn the passing of the Red Men… like a heartbroken parent, it soon faded and died. And now stands with its widespread and whitened branches held aloft as a silent monument of the lamentation in memory of her lost children.”

William Russell O’Neal confirmed this theory. He wrote in 1937, “there stood, the bleached trunk and bare widespread branches, an immense dead live oak tree — hard by the monument erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution on the site of Fort Gatlin.”

Hard by is an antiquated term, but it Cambridge Dictionary defines it as “very near.”

West Side of Pine Loch

One of the most common purported locations is further north of Fort Gatlin. This claim places it on the west side of Pine Loch, along the Old Pine Castle Road. This version seems to spawn from historian Kena Fries’ recollection in her 1937 book “Orland in the Long Long Ago.”

She says, “on the west side of Pine Loch Lake, where the old trail wound its way thru the pine woods, there once stood an immense live oak, said in its glory to have been the largest live oak in all of central and south Florida. It was known as council oak, the gathering place of the Seminole warriors.”

In the following decades, newspaper reports seem to back up this theory. However, upon closer inspection, they merely paraphrase the words from Fries’ book.

East Side of Pine Loch

Upon closer inspection, Fries seems to contradict her own claims just two paragraphs later. She tells a story about how she visited James Madison Alden, who was living in the Eppes home at the beginning of the 1900s. She and Alden rowed across the lake to visit the ruins of Council Oak.

“In September 1904,” she explains, “while spending the day with the late J. M. Alden we rowed across the lake. I picked up a chip with the most peculiar markings and shape, closely resembling a watch dog.”

Given that the Eppes-Shine-Alden estate was on the west side of the lake, along the old road, rowing across the lake would have brought them to the east side of Pine Loch. The book was written in 1937, more than three decades after the incident. It seems to me the 70-year-old historian mixed up the directions in her words.

Need more proof?

Two decades earlier, we find confirmation from the Orlando Sentinel’s interviews with Alden himself. In those days, the estate encompassed hundreds of acres around the lake, including a large citrus grove. The family home was along the single-lane dirt trail, now Delaney Street (Osceola Avenue did not yet exist).

The 1913 newspaper report says the home lay “to the east of the Pine Castle Road overlooking Pine Lake… The house stands on an elevation overlooking the lake about one hundred yards distant, and the walk from the front door to the lake is bordered by an abundance of flowers peculiar to a semitropic climate… The home is surrounded on three sides by orange grove.”

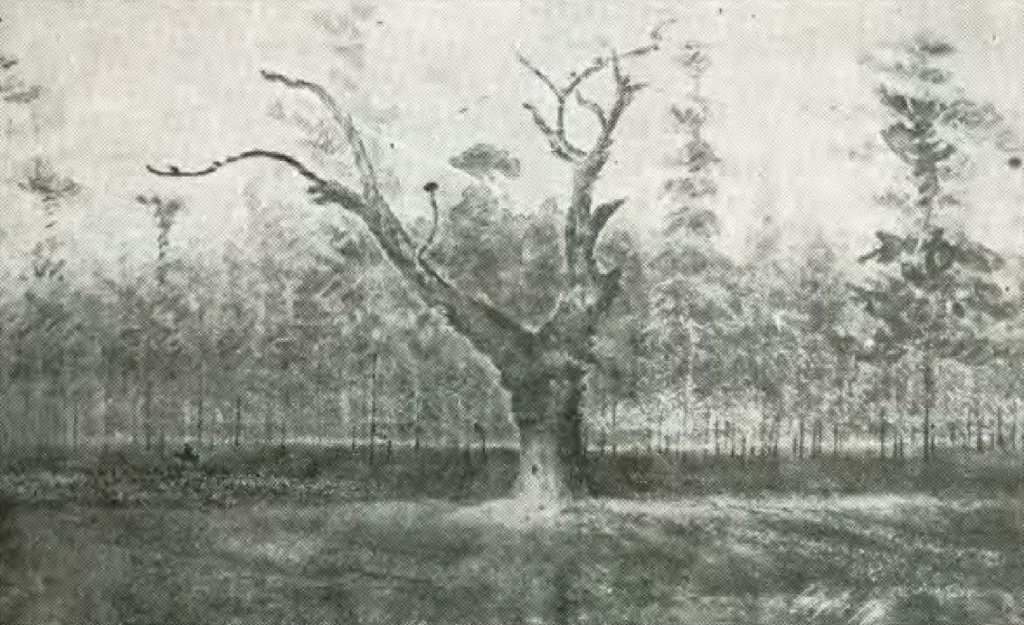

Alden reports that, in the early days of his residence on Pine Loch, he could see the tree from his second story. Alden, a nationally renowned artist, was fascinated by Council Oak. He painted several watercolor paintings of it. Though the originals have been lost (including one donated to the Orange County History Museum), its black and white copies are today the best-known impressions of the relic.

“Across the lake eastwards,” Alden said in 1913, speaking of earlier years, “could be seen from the upper windows, a grand old live oak known for many years as Council Oak of the Indians. A picture of this before its fall has fortunately been preserved by the present owner of the grove.”

Shortly after the article, 80-year-old Alden and his wife Frances moved from Pine Loch to a home on Gore Avenue in downtown Orlando. The Orlando Sentinel spoke with the Aldens again in 1915.

“The Indians,” the article explained, “formed the habit of gathering under a huge oak which stood on a knoll east of the lake now known as Pine Loch… This oak was peculiar in that it was one among a forest of splendid pines, and the rise in the ground at that place gave the spot a commanding view of the surrounding country.”

It continued: “From the frequent councils of the Seminoles, the tree became known as the ‘Council Oak.’ It was of great size and was standing until about ten years ago, when, either because of a woods fire or for some other reason, the tree died. For some time, the trunk remained, and it is a pity that this could not have been left as a historic relic. But the worth of the nearby pines was great, and after the trees had been tapped for turpentine, the entire tract of land was cleared, and not a tree, even the ‘Council Oak,’ was spared.”

Now, let’s put it all together!

Will the real Council Oak please stand up?

The evidence points to one simple answer: the legends reference at least two distinct trees!

The actual Council Oak of Seminole lore was probably located near the Skycrest subdivision, east of Pine Loch and south of Lake Willisara (once a single lake). The topographical map indicates a distinctive rise in this location. The giant live oak on the hill among the surrounding pines would match the description of being clearly visible eastward across the lake from the Alden home.

This is the Council Oak, where the chiefs met to discuss and plan. It thrived for centuries until it was struck by lightning around 1890. After that, its dead trunk and tired branches persisted past Fries’ visit in 1904, but some settlers chopped up its bleached skeleton for fence posts sometime around 1910.

Meanwhile, the great tree nearer to Fort Gatlin lived on for a few more decades. It was within a short walk of the fort and south of the Eppes-Shine-Alden property. Both Alden articles distinctly refer to this as a separate tree and indicate it had a marker bearing the name “Gatlin Oak.”

“There is one the largest Live Oaks in the county in the south end of the grove,” the 1913 article says in the present tense, “nearly eighteen feet in circumference.” The 1915 report says: “Between Lake Gatlin and Lake Jennie Jewell is a tree-covered ridge, and in the cluster of especially fine specimens near the Beardall camp, is one bearing the inscription, ‘Gatlin Oak.’ This stands on what was the parade ground of Fort Gatlin.”

The Beardall Camp referenced here was the country retreat of prominent Orlando medical doctor Hal Beardall and his family. It was located on the shores of Lake Gatlin. It was sold to developer H. Carl Dann in 1916.

Unlike the Council Oak east of Pine Loch, this “Gatlin Oak” was still standing in the roaring 20s. This location, proximate to Fort Gatlin, is where the military officials and Seminole chiefs met in talks of a treaty.

Though agriculture and sprawl have erased any visible trace, the magnificent history of these prehistoric giants lives on. Despite years of confusion and conflicting recollection, the rediscovered clues presented here help us to narrow their precise location. In doing so, we memorialize the natural wonders and the people who once held them sacred.