Old South Bar-B-Q Ranch

Weary travelers for four decades were kept awake by the funny signs and nourished by the taste of this Clewiston oasis.

There aren’t many roads more desolate and monotonous than going south on US 27. Once you pass Lake Placid, you better hope you don’t need to use the restroom. Two decades ago, heading down to Miami or the Keys, the one thing that always kept it interesting was the signs!

The first collection was the rustic witticisms erected by Tom Gaskins, advertising his Cypress Knee Museum in Palmdale. He nailed the first cypress-carved letters to trees in 1951 and ended up with 58 of them in all, including one south of Venus that said “Lady, if he don’t stop, hit him with a shoe.”

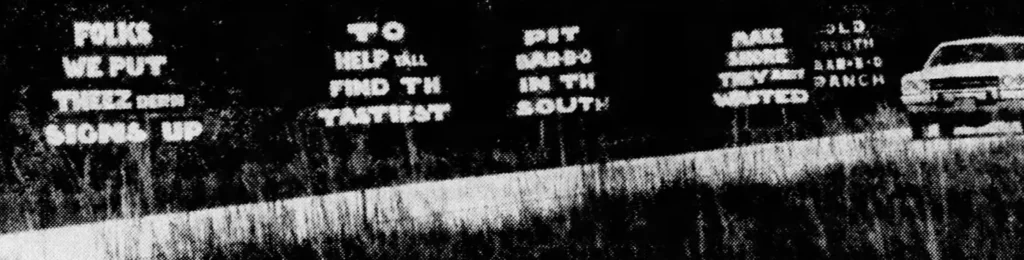

Gaskins’ signs were joined in 1956 by the small tripod signs of Old South Bar-B-Q Ranch. They were arranged in a series (about a tenth of a mile apart) spouting corny Southern humor, followed by a final one with the restaurant’s name. They were inspired by shaving cream company, Burma Shave, whose signs first appeared in the mid-1920s and enthralled generations of travelers nationwide before the last of them came down in 1963.

Old South Bar-B-Q Ranch signs included phrases like:

- “It’s so good / it’ll make you sass your grandma / tenderer than a mother’s love”

- “Folks Be Sure N Stop / So Ya Kin Help / Pay Fer Theez Durn Signs”

- “A quarter is not as good as a dollar, but it goes to church more often”

- “If Yore Mind Goes Blank Be Shore N Turn Off The Sound”

- “Don’t Yall Be Stoppin At Some Other Confounded Place”

- “Jest 20 Minutes Down The Road / Eat Like Hellen B. Happy”

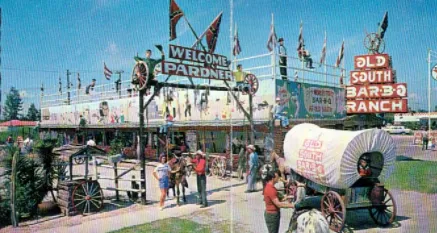

The signs lured weary travelers, but once they arrived it was apparent this was no ordinary restaurant. Old South Bar-b-q was more of an attraction than a simple lunch stop.

It all started in 1956. James Norris McCorvey was a 38-year-old former movie and stage actor who was living in Hialeah. McCorvey was featured in some 20 movies during the 1940s under the stage name Jay Norris. On a long trip along Highway 27, he drove his pink Chrysler convertible past miles of sugarcane fields. The white-haired B-lister came upon a small beer joint in Clewiston and decided he could use a pitstop.

For some long-lost reason, Jim was struck with the idea that this desolate location might just be a great investment for a restaurant. He offered to pay the bar owner $100 a month for 80 months, for a total of $8000, to buy the place. A handshake deal was struck immediately and Old South BBQ Ranch was born!

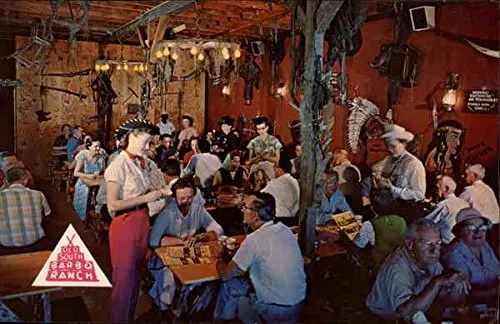

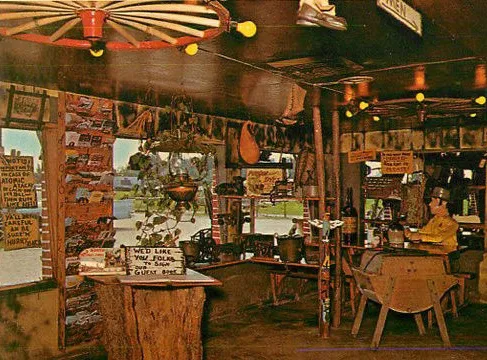

McCorvey transformed the old place not just from bar to fake-brick-painted restaurant but made it into a makeshift historical museum. He collected relics from a bygone era that adorned the inside, outside, and even parking lot. Visitors browsed the collection, took photos, and chuckled about the redneckisms posted on the walls. Most out-of-towners didn’t leave without picking up a postcard, which featured either a photo of the exhibits or a drawing of the covered wagon with their favorite punchline.

The actor-turned-restaurateur never lost his flair for showmanship. “Big Jim,” as some friends called him because of his height, threw himself into every opportunity to grab headlines.

During the early stages of the Space Race, it looked like the Soviets were going to be the first to reach the moon with their Sputnik program. Being that Old South signs were advertising throughout Florida, McCorvey supposedly thought “why not throughout the universe?”

He sent a cablegram to Russia in 1957, asking Soviet Premier Nikolai Bulganin how much he’d charge to post signs on the spacecraft and on the moon. While he got no response, McCorvey was sure to send copies of his letter to news agencies throughout the world, including Reuters. The stunt earned him quite a bit of free press in newspapers throughout the country.

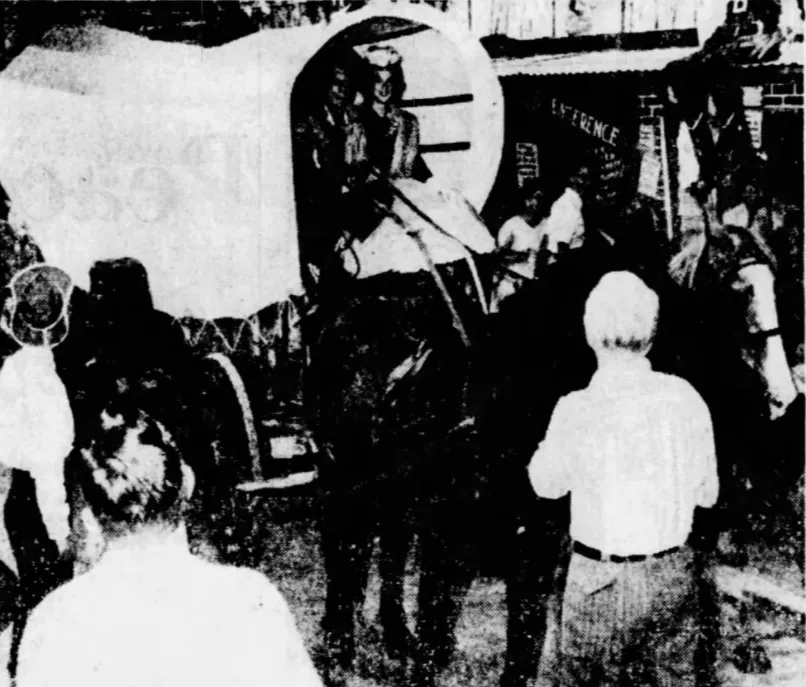

Two years later an Old South waitress named Claire was set to marry a local cowhand named Robbie Robinson. Once again seeing the opportunity for some cheap publicity, McCorvey told the couple that he’d pay for their honeymoon in Miami Beach. Under one condition: they had to transport themselves from Clewiston to Miami via covered wagon.

The newlyweds married on November 22, 1959 and immediately set off on the 150-mile journey, being pulled along a three miles-per-hour by the horse team of Charlie and Babe. Cars honked at the couple and swerved around the buckboard conveyance, which carried signs on it saying “Fountainbleau Hotel ‘er Bust” and “Jes’ Got Hitched.” The trip took them four long, plodding days.

McCorvey’s next stunt was running for governor in 1960. He announced his candidacy in February by mailing himself a 10’x5′ postcard made of plywood, signed by 75 Floridians supposedly asking him to run. The delivery, being carried into his office in Hialeah by two postmen, was covered by the Associated Press and appeared in several papers throughout Florida.

The entrepreneur and spotlight hog had no real platform nor any serious desire to go into politics. But he was good at pretending he did. Although his campaign was low-budget and completely self-funded, he continually created a spectacle, grabbed the attention of newspapers, and appeared in debates for the Democratic primary race. It was all one big commercial for his ego.

McCorvey identified the core plank as the legalization of Bingo gambling. In March he promoted a community Bingo game at the Suncoast Roller Rink in Bradenton. Local officials warned him that he would be arrested if he went through with the plans, but that was exactly what he had in mind.

Over 300 local senior citizens gathered for the game, as officers stood by waiting. McCorvey served as the caller and just after 9 PM several players yelled “Bingo!” The would-be governor handed out a $1 prize to each of the winners (and although no entry fee was charged to play) he was arrested.

McCorvey and two other campaign officials were taken down the station by the Bradenton Police Department. Campaign staffers were already waiting at the station. Although they had no desire to actually lock him up, McCorvey’s lawyer insisted on the habeas corpus, and officers reluctantly booked him on charges of running a lottery. After a free night’s lodging at the jailhouse, the $500 bail was posted for the three men. Charges were eventually dropped.

Despite the significant amount of press, including front-page headlines for his Bingo arrest, McCorvey was not taken seriously by voters. He ended the Democratic primary in May placing tenth (in a field of 10) to eventual general election victor C. Farris Bryant. McCorvey received just 5,080 votes (which represented 0.54%). Even in his home county of Dade, he finished a distant ninth place with less than one percent.

Regardless, he had achieved his goal: statewide publicity!

With any political aspirations thoroughly rejected, McCorvey turned his ambition to another arena. Unsatisfied with just two locations (he opened a second on Tamiami Trail in Ft. Myers in 1958), he decided he could multiply his themed-restaurant success by turning it into a chain.

Between the summer of 1960 and 1961, McCorvey opened additional locations in Hialeah, Tampa, Old Town (a small village on the Suwanee River), and Orlando. The corporate office was located near his home in Hialeah.

McCorvey traveled around the country, like an episode of American Pickers, searching for antiques and pieces of Americana to decorate his planned barbeque empire. He added a warehouse in Hialeah to store the many treasures he collected from as far away as North Dakota.

However, the franchisees never came. Strapped for cash after the expenses of the governor’s race and under the weight of debt from the struggling new locations, Old South Bar-b-que Ranch filed for bankruptcy a year later.

That’s when Carroll Benson stepped in to rescue the iconic restaurant. He purchased the original Old South location in Clewiston (the only one to survive) from McCorvey in 1961. Benson moved to sugarcane country from Maryland and became a prominent Clewistonian for the next 25 years, including tenue are the Chamber of Commerce president.

Benson, himself an avid antique hunter, did what many may have thought was impossible: he one-upped McCorvey on the gaudy decor and went hog-wild on over-the-top displays. Additional signs were put up on roadways and new Western scenes and artifacts were added.

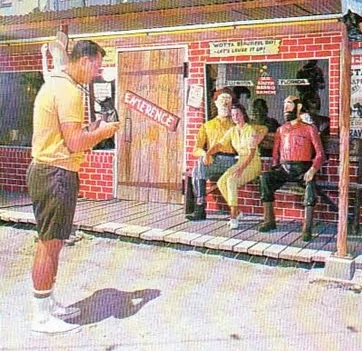

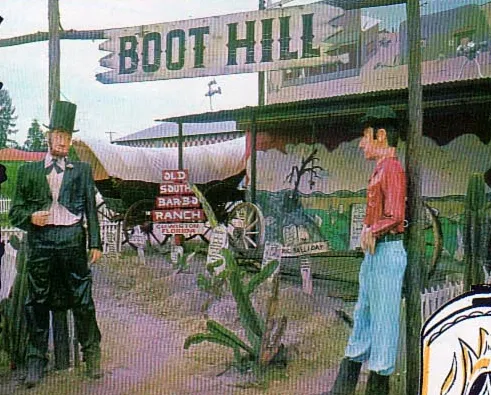

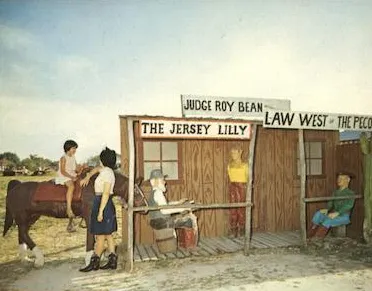

Eyes failed to take in all of the displays. There was the famous 125-year-old Conestoga stagecoach (the same one that rode to Miami in McCorvey’s stunt) that greeted new arrivals, along with dozens of mannequins posed around the building — or hanging from it. The model of Boot Hill cemetery was particularly popular with comical headstones such as “Here lies Jim, a native son, fast wit wimmin, slow wit gun.” There was a wide variety of cactus species, Rebel flags, murals, mock-up of Roy Bean’s (“the hanging judge”) infamous court, misspelled signs galore, and that was just in the parking lot.

Once you went through the “enterence” that’s where the real eye-full began. There was hardly a bare spot on the walls or floors. Benson had collected over 200 flat irons, working player pianos, music boxes, pioneer-era metal bathtubs, all sorts of manual machines and tools, dozens of varieties of barbed wire, wooden washboards and basins, nickelodeon jukeboxes, 19th-century kitchen utensils, butter churns, antique telephones, cornhusk mops, and cigar cutters. The walls had newspaper clippings and magazine ads from early in the century advertising horse-drawn carriages and other throwbacks. There was authentic Confederate currency and fractional-cent US-minted coins. Hundreds and hundreds of authentic pieces had been meticulously curated.

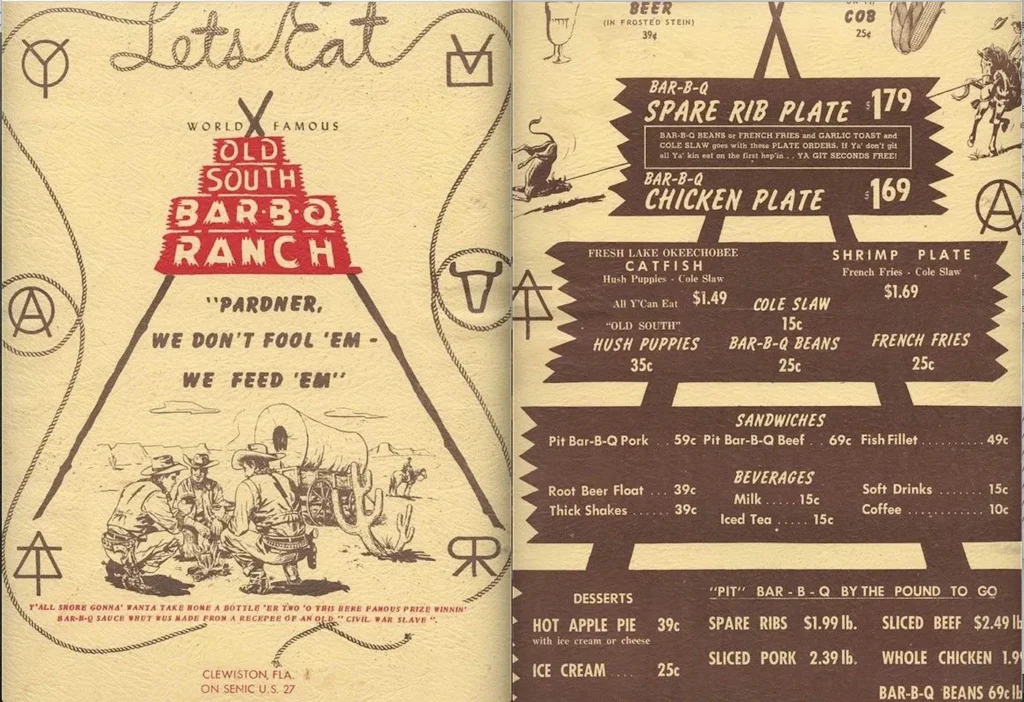

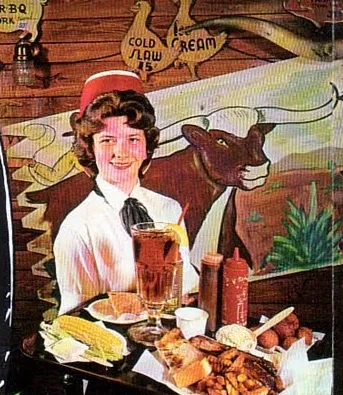

Benson had the cowgirl-garbed waitresses carry around six-shooters strapped to their waist. These were actually cap guns, which the ladies occasionally fired in mock gunfights to startle unsuspecting guests. The menu was small and affordable and famously granted diners free seconds if they were not full!

During the restaurant’s heyday, it was said that over half a million people visited each year. The landmark became a must-stop for not only the general public but celebrities too. Red Skelton, Lawrence Welk, William Shatner, and Mel Tillis dined there. For several years it was a big to-do around town when the contestants from the Miss Universe pageant made their annual stop for lunch on the way to-and-from Miami. The mayor and the local Sugarland Band gladly came out to welcome the international ladies.

It all almost came to an end in October 1978. During the early morning hours, there was a short behind a jukebox and the place went up in flames. The fire department rushed to the scene and it took two hours to extinguish the blaze. The damage was extensive, but Benson rebuilt and refurbished the institution. Saved for another generation!

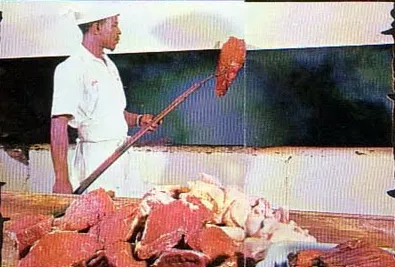

The crazy exhibition may have gotten travelers to stop, but it was the food that kept them coming back. And during the glory years of Old South BBQ, there was one woman to thank for those delicious meals: Janie May Watson. When McCorvey originally founded the place, he recalled the homestyle cooking of Watson from his younger days in Georgia.

Watson was a black woman who worked on his father’s farm, and her culinary delights had forever left an impression. So when he opened Old South, the first thing he did was summon Watson to come down to Clewiston.

She put in over 40 years of service to the Old South Barbeque Ranch. Watson was the head chef, even though in the early years she (being black) would not have been allowed into the dining room. She ignored the Confederate flags. She looked past the life-sized plump mammy statue (think Aunt Jamima) that greeted guests at the front door. The caricature, which may have been meant to represent her, held a frying pan that said “Welcome Podner.”

The famous sauce, which Benson first bottled and sold in the gift shop, was her secret recipe. The bottles claimed the concoction was “made from an old Civil War slave recipe.” And a later owner once made a mathematically impossible boast to the Palm Beach Post in 1996: “I’ve got a lady that’s been here since slavery days,” referring to Watson.

Despite being used as a prop at times, Watson out-lasted four different owners at Old South. Into the late 1990s, by then in her eighties, she still made the hush puppies and served as the figurehead for the back of house.

Carroll Benson continued to run the restaurant for another decade until finally the 14-hour days finally got to him. The 70-year-old decided to retire from the restaurant business in 1987 and sold the establishment to Clewiston mayor Jimmy McDuffy.

McDuffy did his best and had a few successful years, but never had the same gusto for the business nor passion to maintain the displays. The loyal patrons slowly began to thin out over the next decade.

The mayor sold the restaurant to Anthony Pepe in 1994 and things only got tougher for the business. Pepe took out a mortgage on the property in 1995, but whatever investments were made didn’t improve things much. Fewer tourists seemed to pass Clewiston every year and the local economy puttered.

The final nail in the coffin for Old South came in 1998 with a road-widening project of US Highway 27. The heavy construction cut-off would-be customers from seeing the displays and re-routed traffic made access to the parking lot difficult. The $4,182/month mortgage payments proved too much for Pepe to bear and the bank foreclosed in March 1999.

The building and signs are gone. There are no more concrete alligators, wooden wheels, nor saddles on display. The smell from the smoker has long since dissipated. But the memories persist in the thousands of now-grown children that still remember hunting for the next set of signs and romping around the colorful displays of this barbeque oasis in the middle of sugarcane and cattle country.

This post is 1739 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.