Mayaca-Jororo, the native people of Orlando

If you ask most residents who lived in Central Florida when the Spanish arrived, they’d probably tell you the Seminoles. However, the Seminoles didn’t even exist when the Spanish arrived. Instead, they were bands of refugees fleeing to Florida long after those early nations were wiped out.

Long-time residents of the Orlando Metro might smugly correct that myth, insisting that the Timucuan tribe called the area home when Ponce De Leon first arrived on Florida’s east coast. While this has been traditional lore in the region (even cited in many books), this too is incorrect—instead, the Mayaca people called the upper St. Johns River valley home.

Let’s first discuss the nature of these Indigenous communities. They were not well-organized nations or homogeneous people. Instead, they were confederations of loosely coupled clans under hereditary leaders. The lines and borders between one another were dynamic and easily blurred. Larger super-groups were united in culture and language, while local sub-groups jockeyed for power and influence against each other in a series of continually forged and broken alliances.

The journals of Spanish, English, and French explorers and missionaries are our best sources for determining each group’s distinct identities. After their arrival, Europeans became key players in the geopolitical games between tribes. Leveraging them against each other with promises of alliance and wealth, the white invaders used chiefs as pawns in proxy wars.

By Jason Byrne

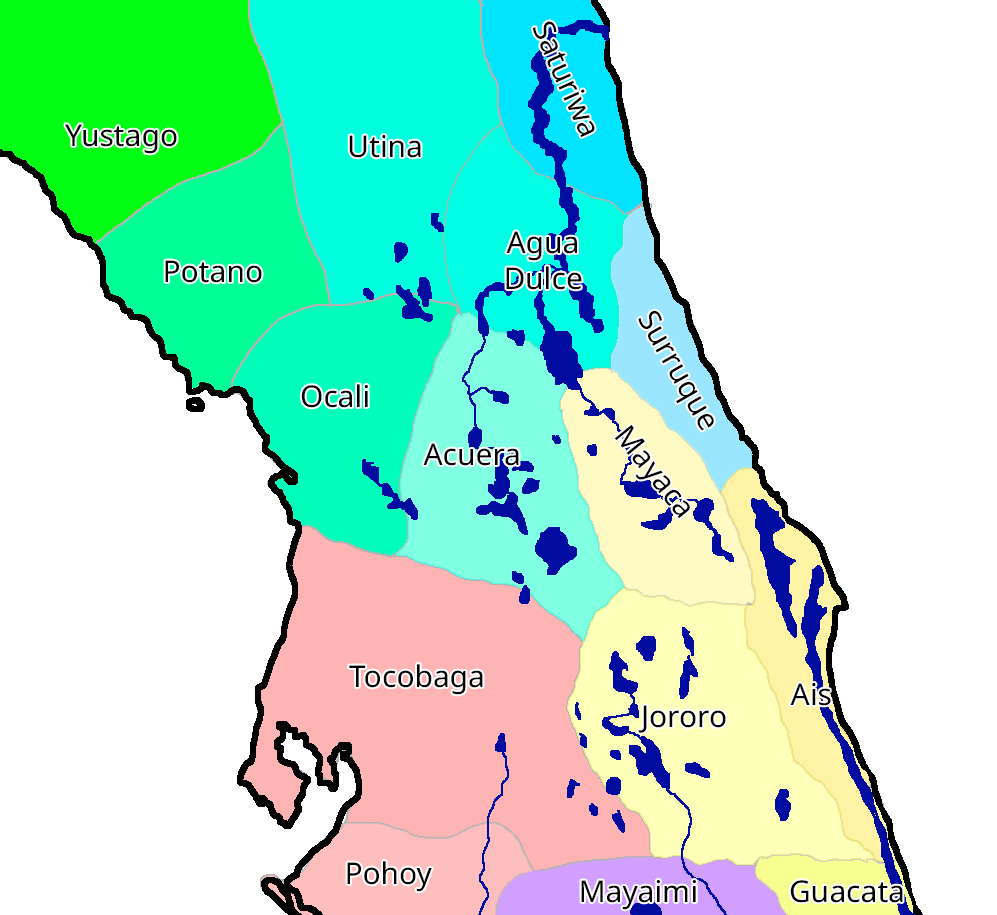

The Timucuan people were a dominant force within the northern Florida panhandle and the lower (north) St. Johns River, but they were not a nation. The confederation of Timucua tribes shared a common historical lineage, language, religion, and culture. However, each spoke distinct dialects, had a local chief or “cacique,” and were often at odds with each other.

The Agua Dulce (“freshwater”) Timucua dominated the middle St. Johns River around Lake George and Palatka. They were closely linked with the Utina Timucua toward their northwest, sometimes called “Timucuan Proper.” They constantly feuded with the saltwater Timucua (Surruque and Saturiwa) to their east and the Acuera, Potano, and Ocali Timucua to their west.

As a whole, the Timucua were village builders with structured hierarchal communities of up to 1,000 people. Since they were an agricultural society, they settled in one area for an extended period. They produced a variety of food crops, including corn, beans, squash, pumpkins, cucumbers, peas, sunflowers, berries, and nuts. They understood concepts to improve yields, such as irrigation and a “slash and burn” method to create better soil.

In contrast, the Mayaca people of the upper (southern) St. Johns River had a more nomadic existence. Their villages were generally smaller and less permanent, more like camps. They did not plant crops or raise livestock. They sustained themselves by hunting game, fishing, gathering wild fruits and berries, and collecting freshwater snails.

The Mayaca people are sometimes considered a sub-group of the Ais people, who lived on the Atlantic Coast along the Indian River from the Canaveral National Seashore south to the Port St. Lucie area. The Mayaca spoke a dialect of the Ais language, distinct from Timucua. Mayaca-Ais may be related to other South Florida native languages; some say it was mutually intelligible by speakers of Tequesta (southeast Florida) and Calusa (southwest Florida). However, very little of it was ever written down by Europeans, and it is considered lost.

The Jororo inhabited the land south of the Mayaca. They were another Ais-affiliated tribe, with territory ranging from the Orlando lakes to the Kissimmee River valley. The Mayaca and Jororo were strongly linked, both being interior freshwater people who survived on the bounty of the rivers and swamps. Some historians sometimes consider the Mayaca-Jororo territory a unified Ais province.

A shipwrecked Englishman named Jonathan Dickinson reported visiting an Ais village in 1696. He said it was completely hidden from view by mangroves. Their homes were constructed of thatched palmetto walls and ceilings.

Dickson noted that most families’ dwellings were petite huts, but the cacique’s cabin was relatively large. It was 20 feet wide and 40 feet long, with a hallway and benches in the middle, sleeping quarters on the sides, and a fire pit kitchen at the end.

The coastal Ais in Brevard, Indian River, and St. Lucie counties frequently interacted with European visitors. They forged alliances with the Spanish, salvaged wrecked ships, and cared for stranded white men who washed up on their shores. Conversely, the inland Mayaca-Jororo had far less frequent exchanges with these explorers and preferred to keep it that way.

Spanish Plantations

The Spanish had two main intentions in their first two centuries of Florida settlement: Christian missionaries and farming. The missions are well known, but fewer people realize that the Spanish settled vast tracts for growing produce and cattle ranches. The Timucuan groups were well-suited for this kind of work and were recruited (whether by partnership or by force) to supply the labor. However, the Ais groups in Central Florida proved of little value since they did not practice any form of agriculture.

“On the whole [the Mayaca] do not work at plantings. They are able to sustain themselves solely with the abundance of fish they catch and some wild fruits”

Friar Juan de Torquemada, 1693 (Hann 1991:111)

The Spanish government looked at them in disgust. Not only could they not provide labor, but they lacked any accumulation of wealth from their hunter-gatherer way of life. So, they could neither offer tributes to the Spanish crown nor be worthy trade partners. A Spanish governor said they were “a poor and miserable people who sustain themselves with nothing but fish and roots from the swamps and woods.”

For the first few decades, the Spanish missions lined up primarily through Timucuan territory along the Camino Real in northern Florida, a royal road from St. Augustine to Tallahassee via Gainesville. Early attempts to penetrate further down the winding St. Johns were quickly deflected.

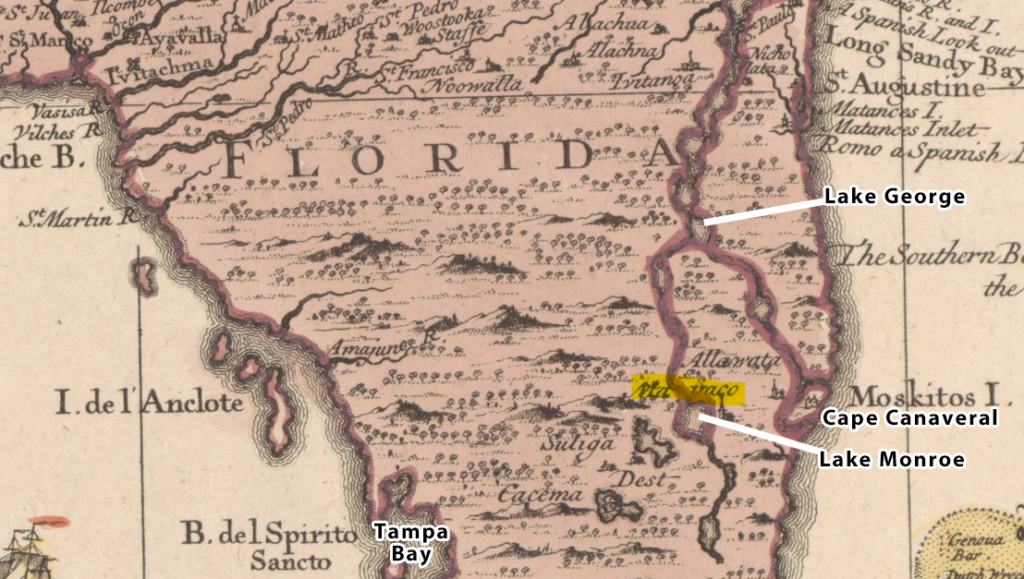

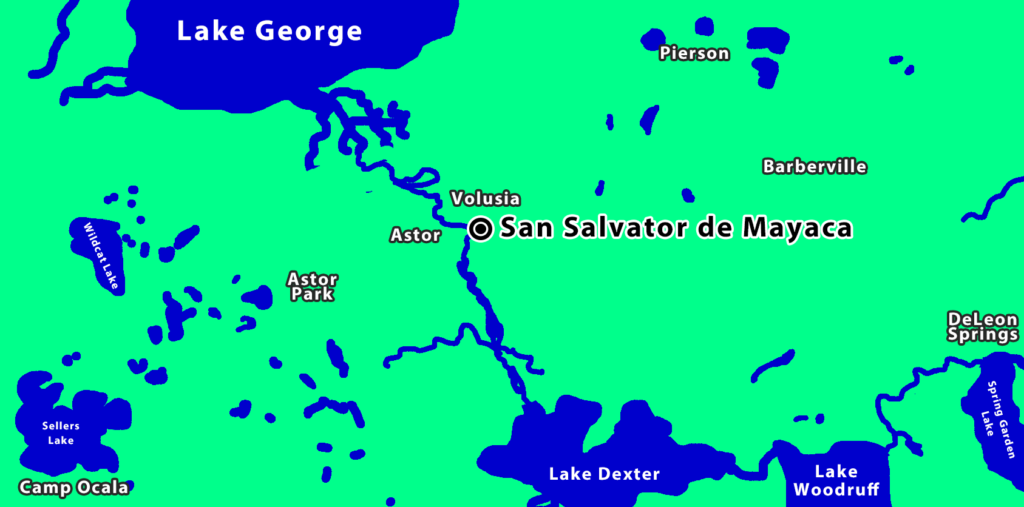

Pedro Menendez de Aviles was the first to encounter the Mayaca in 1565. He led an expedition down the St. Johns River south of Lake George, arriving at a Mayacan village near Astor. The villagers fled, but tribal scouts observed from a distance. The local chief sent word to St. Augustine, warning them not to venture further south along the river; Menendez scoffed at the demand.

Menendez sent a crew of fifty to continue in row boats. The St. Johns narrowed around a bend a few miles past Lake George. The Spanish found the waterway blocked by a row of stakes across the navigable channel; they broke through and pressed onward.

Upon reaching another narrow point, they encountered the Mayaca warriors along the banks. Armed with bows and arrows, they prepared to strike. Menendez paused the advance and set up camp for the night. He attempted to negotiate passage, but the natives insisted they’d kill them if they went any further. The general weighed his options before avoiding bloodshed by returning to St. Augustine. A native interpreter guide told them the Mayaca were “many and very warlike.”

Although the wilds of Volusia and Seminole counties would have offered the Spanish valuable land to expand their ranches and farms, they mostly took the hint. This far interior was the uncharted and unfriendly frontier. The Mayaca and Jororo were largely left alone for the next hundred years.

During that century, the Spanish mainly focused on northern Florida’s Timucua and Apalachee regions, along the Camino Real, for ranching and missions. However, those communities were decimated by European diseases such as smallpox and harsh conditions of forced labor. The Timucuan population plummeted from over 200,000 to 30,000 after just a century of Spanish and French interaction.

With the shortage, Spanish demands became ever more oppressive. Timucuan chiefs were reluctantly compliant when they were permitted to retain local authority. That changed when the Spanish forced even the tribal royalty to carry 75-pound grain sacks on their backs up to a hundred miles to St. Augustine. The policy change resulted in a large-scale rebellion across the Timucuan provinces in 1656, causing hundreds or thousands more to die in the fighting. The Timucua numbers dwindled.

The Spanish needed more laborers, so they began to look toward the interior tribes again. Despite the best efforts of the Mayaca, they could not hold out forever. Even in the deep forests and swamps, they were no longer safe from Spanish bayonets, Bibles, and epidemics.

Spanish Missions

In 1655, the Spanish founded the first mission in Mayaca territory, called San Salvador de Mayaca, at the site of the Mayacan village that Menendez encountered a century ago. Two years later, a building was constructed from a coquina-like concrete mined from the native’s shell mound and mixed with lime and ox blood shipped in barrels from St. Augustine.

The friars tried to educate the native children, indoctrinate the Christian religion, and teach them about farming. Finding little interest from the natives, the first iteration of the Spanish enclave did not last long. The ill-supplied mission disappeared from records by 1660.

Uprisings by various tribes throughout Spanish Florida became more frequent and fervent. The Spanish response was brutally effective.

In 1679, the San Salvador encampment was revived. Knowing the fate of their neighbors, the Mayaca didn’t provoke the Spanish outright. While a few settled into mission life and converted to Christianity, most remained secluded deep in the wilderness.

Members of tribes of northern Florida and Georgia were moved into the region to fill the population and labor vacuum, with many being located at missions in the Mayaca-Jororo province. The Yamasee, a tribe from coastal Georgia, comprised most of the San Salvador population in 1690.

Between this encroachment of the Spanish and rival tribes, the Mayaca people had a choice: assimilate or retreat. A faction settled into the missions or a host of villages close to St. Augustine. Others, however, unified with their Jororo kin and headed further south into the uncharted creeks, forests, islands, lakes, and swamps.

Those who peacefully assembled into villages near the Spanish were taught to farm, although they never embraced it. Records tell that they’d often abandon the town, preferring the freedom of hunting and gathering that had always been their way. These Spanish-affiliated villages did not last long; most natives died of diseases for which they had no defense.

Between 1690 and 1706, there were four missions in the Mayaca-Jororo territory (San Salvador being one), each located about 30 miles apart. They were sparsely populated and had limited success winning converts. One mission was located near Lake Kissimmee—referred to as Atissimi or Jizime (the source of Kissimmee’s name). The others were called San Joseph de Jororo and La Concepción de Atoyquime, but their locations are unknown.

Periods of tranquility were often interrupted by violent uprisings. Spanish mistreatment of natives led to soldiers, friars, and their guides being killed. As a result, the Spanish hunted the guilty parties, which often led to more violence.

One example is the Jororo Rebellion of 1696-1697. It was sparked when some natives were harshly punished at the Atoyqime mission. The Jororo attacked and killed the friar, a complicit chief, and two boys of the Guale tribe. The Spanish governor went on a multi-year search for the attackers.

One such search party arrived at a Jororo village, they were greeted kindly and feigned assistance to track down the guilty parties. The guides led the Spanish deeper and deeper into a maze-like swamp, a three-day walk from the nearest village. There, they abandoned them and took the supplies with them.

Massacre at San Salvador de Mayaca

Volusia pioneer Barney Dillard (1864-1962) remembered the old Spanish fort and mission at San Salvador de Mayaca in a 1957 interview. At 15 years old, in 1879, he helped dismantle it and recounted that they found evidence of a massacre there.

They uncovered skeletons of young children with beads still around their necks. The skeleton of the mission’s friar was found with a Spanish ax in his rib cage. Dillard theorized that the friar was assassinated as he tried to defend the native children in his care.

The white settlers used the coquina excavated from the quarter-acre mission to create roads in the low-lying area nearby. The Spanish constructed it of a cement-like concoction of shell, lime, and ox blood.

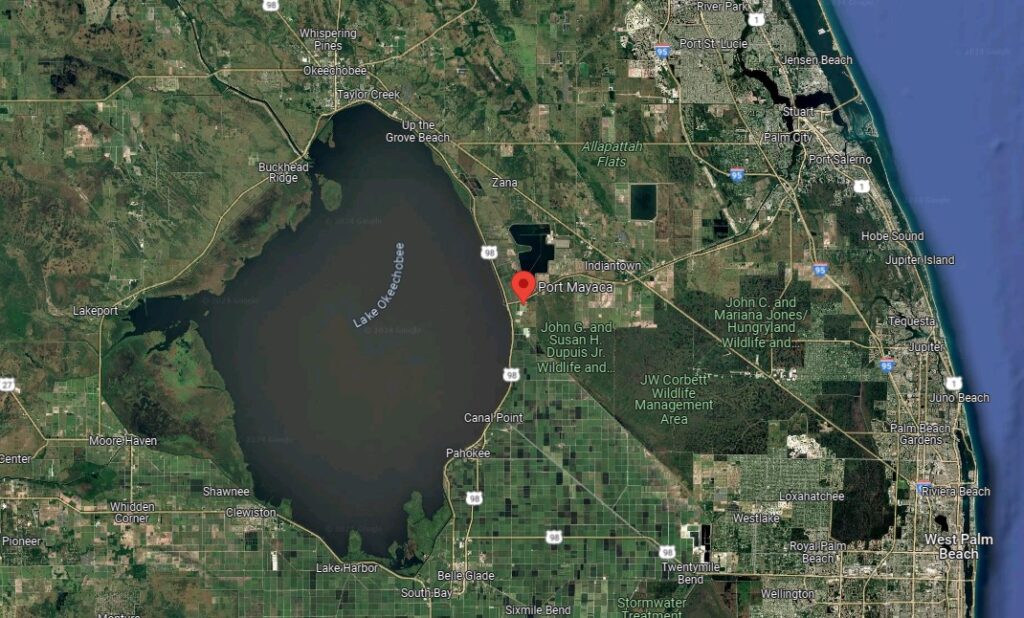

Lake Okeechobee: The Last Stand of the Mayaca

The once-thriving people rapidly declined in just a few decades. The last of the Mayaca-Jororo holdouts lived on the eastern shore of Lake Okeechobee, near the tiny town still called Port Mayaca. The big lake was once called Lake Mayacao for the last resilient tribes that lived on its shores as refugees.

Many of you might have heard of Myakka City and the Myakka River in the Sarasota-Bradenton area. To fend off speculation, as far as we know, the tribe did not establish a settlement there. Their connection with a very similar name is unknown.

By the end of 1739, there were under a hundred left at Lake Okeechobee. By the middle of the century, the tribe had disappeared entirely or, at best, had merged into other nations. Some legends suggest some may have made their way to Cuba, though no provable lineage exists.

Mayaca Settlement on Hontoon Island

Hontoon Island, today a state park accessible only by boat, was one of the primary settlements of the Mayaca that was long falsely attributed to the Timucua. The mound contained many artifacts, food scraps, and pottery shards.

It is named for William Hunton, who homesteaded there in the 1860s. In 1935, the City of Deland acquired parts of the island and used them as a shell mine for roads. In the process, they destroyed centuries of valuable archaeological discoveries. Unfortunately, most mounds in the area share a similar fate.

In 1955, Victor Roepke, a real estate developer planning a subdivision, owned a large stretch of land near the island. Roepke was dredging the river and snagged a ten-foot pine owl totem resting on the bottom of the river. It is thought that it might have once been 15 feet tall but fell over after its base rotted. The purpose of the totem is unknown. Some theories say it was a territorial marker; others say it was used in religious ceremonies or as spiritual protection.

Other large mounds believed to have belonged to the Mayaca were found throughout Volusia and Seminole counties. On the eastern side of Lake Monroe, near Sanford, is Indian Mound Village, home to a large mound. Most artifacts were scavenged or destroyed for shell mining before early anthropologists arrived to survey them. Mounds were used for both trash heaps and burials.

Similar mounds of the Jororo have been found across Orange, Osceola, Polk, Okeechobee, and Highlands counties. Prominent examples exist at Goodnow Mound (near Sebring) and the Philip Mound (near Haines City).

Legacy

Though often overlooked, the legacy of the Mayaca-Jororo endures through the archaeological remnants they left behind and the writings of the Spanish. They should be remembered throughout the Orlando Metro area. These reclusive and nomadic people lived for centuries in harmony with the land we call home.

References

- The Spanish Missions of La Florida, by Bonnie G. McEwan (1993)

- Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe, by Jerald T. Milanich (1995)

- Online Translations of Spanish Documents

- Owl Totem Discovered at Hontoon Island (Orlando Sentinel, 1955)

- History of Volusia County, by Pleasant Daniel Gold (1927)

- Teen Explored Mission site, Orlando Sentinel (1997)

- Mayaca people, Wikipedia

- Demise of the Pojoy and Bomto, by John H. Hann (Florida Historical Quarterly, 1995)

- History of the Mayaca at Hontoon Island (Florida State Parks)

- The St. Johns River: An archival project investigating interior occupation of the St. Johns River Region by Native Americans during the Colonial Period, by James Sutton (Thesis Paper, 2021)

This post is 506 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.