Visit to Lake Harney’s Mansfield Island in 1891

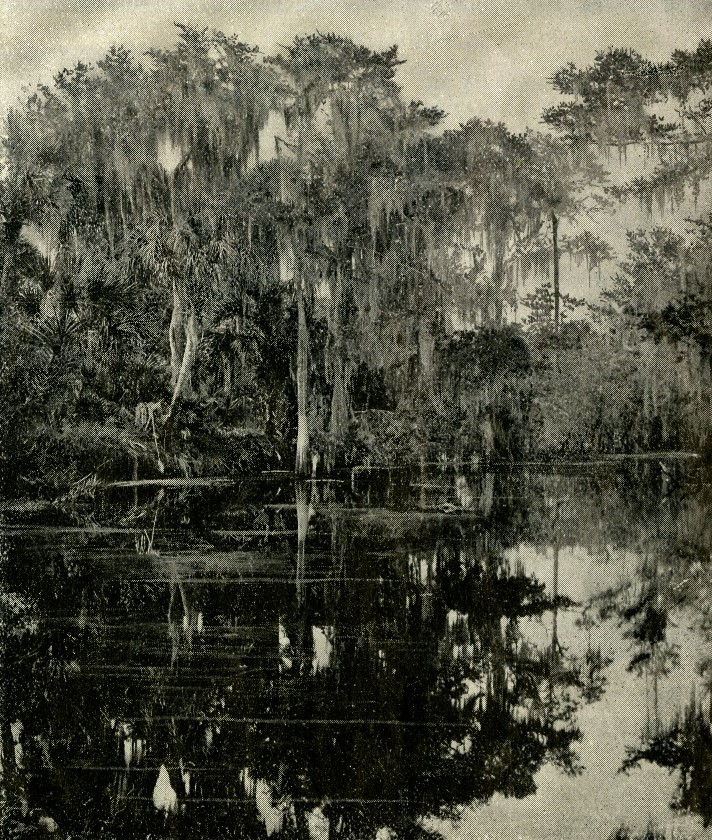

In January 1891, photojournalist Clarence Bloomfield Moore traveled down the St. Johns River with a small crew. It had become an annual tradition since he first journeyed deep into the Florida wilderness in 1879.

Moore was a Harvard-educated archeologist from Philadelphia. He traveled around the world (literally) and navigated the Amazon River in 1876. He became a millionaire running the family’s paper interest but spent as much time as possible studying archeology.

Native American studies in the Southeastern United States fascinated Mansfield, which brought him often to the St. Johns River to study ancient Timucuan Indian shell middens and burial mounds.

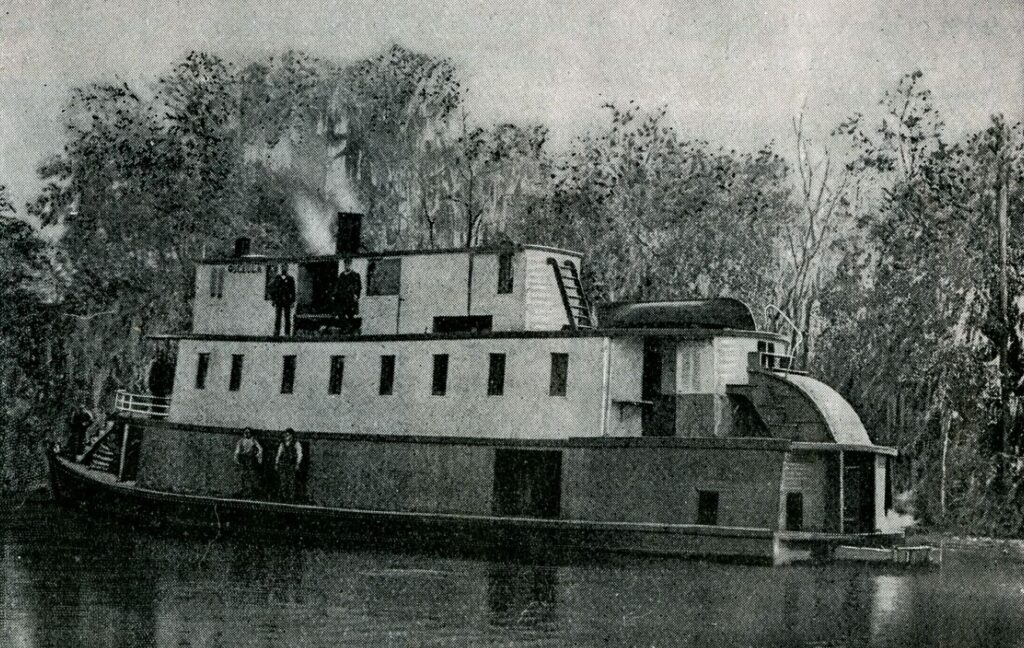

He began the trip, with two companions, at Palatka — a commercial hub and interior port town on the St. Johns River. They boarded a steamship called the Osceola, which resembled a three-story houseboat. Its flat bottom gave it a low profile, specifically designed to explore parts of the river where most other large ships could not.

The large paddlewheel propelled it forward as the visitors crept down the meandering St. Johns. They passed the tributary with the Ocklawaha, crossed Lake George, stopped at Blue Spring, and stocked up on supplies at the Sanford wharf on Lake Monroe.

Most people traveling into Florida’s interior frontier finished here. Moore estimated less than ten tourists per year penetrated further up the river. Once a year, he visited his old friend William H. Mansfield and, this time, he brought along the camera crew.

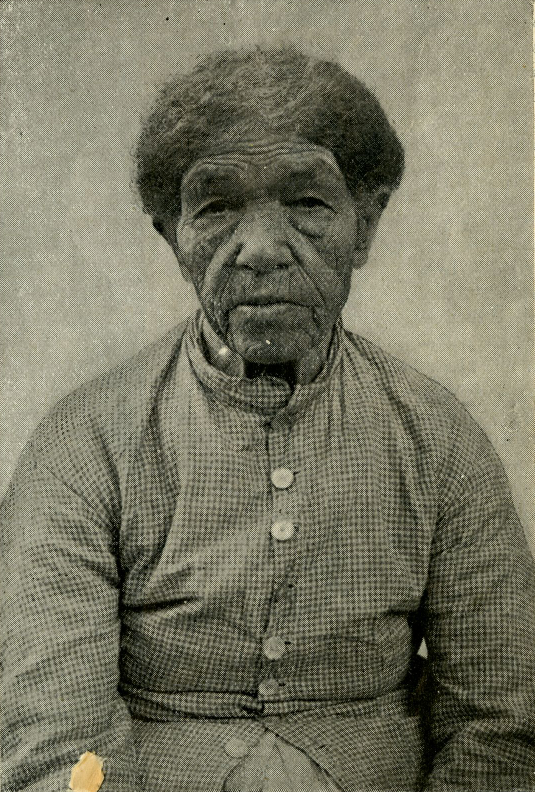

William H. Mansfield was born around 1835 and fought in the Third Seminole War from 1855-1857. He was a Corporal in Captain Durrance’s Company. From 1862-1863 he joined the 7th Florida Infantry (“South Florida Bull Dogs”) to fight for the Confederacy.

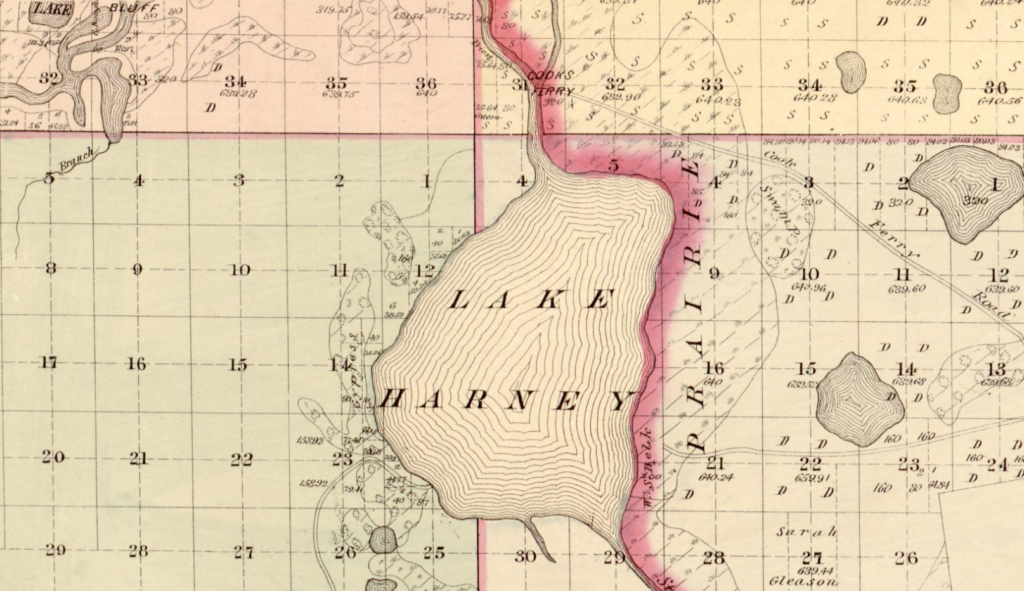

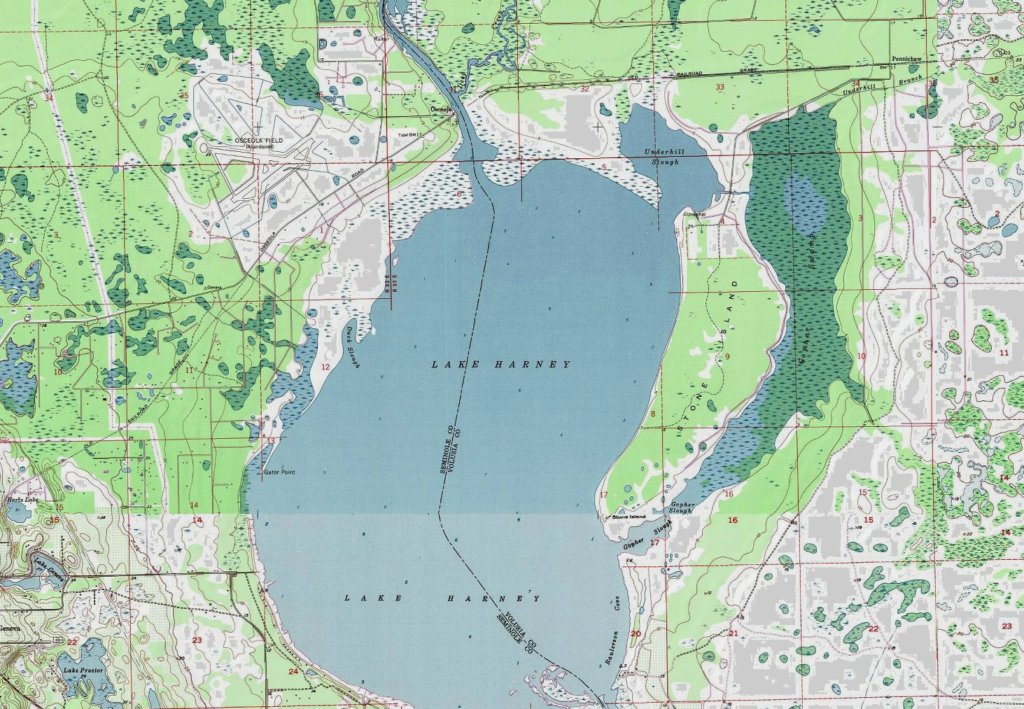

After the Seminole War, Mansfield explored the vast expanse of now Seminole-free Florida wilderness and settled along the eastern banks of Lake Harney in newly-formed Volusia County (split from Orange County in 1854). He was the only settler on the lake.

Mansfield set up camp near the white sandy shores that line the west-facing banks of what is today called Stone Island. During the late 1800s, it was called Mansfield Island. It is connected by a narrow causeway on its north end with the inlet of Underhill Slough to its north and Gopher Slough to its south and east.

Samuel J. Cook offered a ferry barge across the river around 1850 at the lake’s north end. Cook left years before, but everyone still called that neck of the river “Cook’s Ferry.”

The Osceola parked in the mouth of Deep Creek, just north of Lake Harney, and Moore’s crew took the last mile to Camp Mansfield by rowboat. Three barking hound dogs greeted them when they ran their boat upon the white sandy beach, obviously not used to visitors. Their teeth and the tenor of their growls did not give the welcoming feel, so Moore fended off their advance with his oar.

Moments later, Mansfield limped out of the palmetto thicket and insisted they meant no harm. “Don’t mind ’em, boys,” he said, “they won’t hurt you. They only want you to mush ’em.” By Mansfield’s colloquial use of “mush,” he meant the dogs wanted to be patted and rubbed.

After some good “mushing,” the dogs calmed down, and the group proceeded up a sandy trail to the Mansfield cabin. Though it sat on the island’s highest point, the palmettos hid the cabin from view.

The Mansfield home looked more like a Seminole chickee hut than a cracker house. The walls were palmetto thatch, fastened to wooden poles. The palmetto roof had a steep angle that skillfully funneled away the rain.

The dwelling started as a small room but Mansfield expanded it over time with minor additions. It had a small wooden patio out front. They secured the home’s wooden door at night to deter the wildcats.

Behind the living room, which doubled as the bedroom of Mansfield and his wife, a spare room. On this particular visit, it was serving as a guest bedroom for a young relative of the Mansfields, who was visiting to introduce them to her new baby.

The annex formed a right angle from the main living quarters and connected with an open-air kitchen; this gave the main house an “L” shape. The kitchen had an angled wooden roof, providing plenty of ventilation for smoke. It had no walls, mitigating the risk of fire. This was the domain of Mrs. Mansfield, who (although the article does not say) appears to be of Native American descent.

Separate from the main house, the compound had a stable. The two-story building was constructed of palmetto logs with a palmetto-thatched roof. The bottom floor housed Mansfield’s horse, hound dogs, and various animal skins tacked up to dry along the walls.

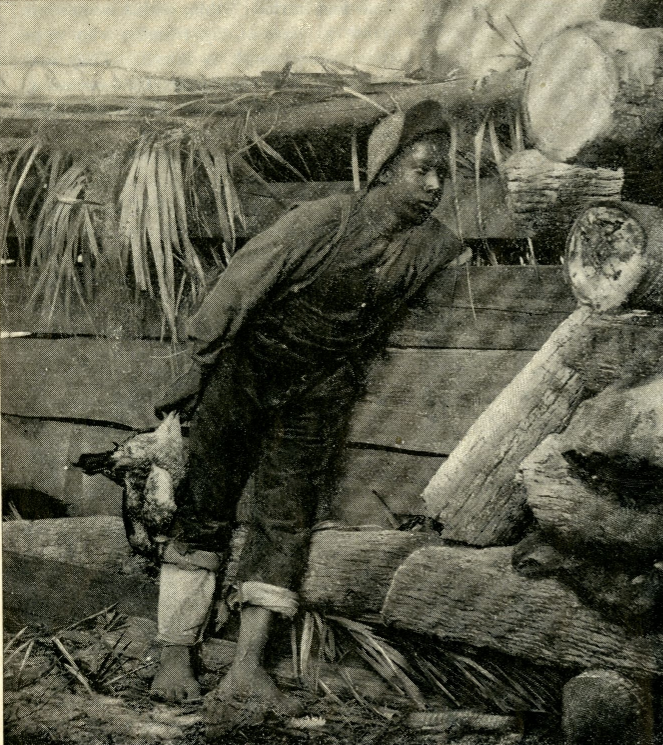

The upper floor was a loft that was the bedroom to Grant, a black teenager who stayed with the Mansfield family as a hired live-in servant. There were no stairs or ladder up to Grant’s loft. Instead, he nimbly climbed the wall by inserting his fingers and toes between the logs.

Grant did much work around the compound, including hunting much of the game that provided the family with meat, covering, and trade. He also helped “the Old Woman” raise their poultry flock in the nearby coops.

Mrs. Mansfield greeted Moore and his crew. “Well, boys,” she said, “I knowed you’d be here. Grant was down to the mouth of the lake last night, an’ he seen the smoke of your steamer. I’ve got two fine guineas fur ye, an’ a lot of eggs.”

She called her husband “the Captain,” although he never achieved that rank. His highest military positions had been corporal and third lieutenant. He was beloved for his stories: some of the Southern frontier living genre, others about peaceful interactions with the Seminoles, and more about the wars.

He lamented the waning health that increasingly prevented him from getting around as much. He no longer could go on deer hunts, and they relied on Grant to do the strenuous work.

“I am having troubled with my foot again,” he told them, “You remember I never had no luck with that foot, nohow. Fust, I ran a nail into it, then a hoss kicked the ankle off, and then I split it with an ax. I give the ax to another man, and he split his foot too; so we ‘lowed the ax was unlucky, and throwed it in the lake!”

The area around Camp Mansfield and Lake Harney had long been a haven for the Seminole Indians. Finding arrowheads (or rifle balls from the Seminole Wars) was a regular occurrence.

The former Seminole settlement of King Philipstown, named for Seminole chief Emaltha (aka King Phillip), was on the Seminole County side of the lake. It was once populated by 200 and 400 natives where the St. Johns River meets the lake, led by Emaltha and his son Coacoochee (also known as “Wildcat”). American soldiers pushed the Seminoles out of the town by the end of the Second Seminole War in 1842.

Nearby is the large midden mound that had first brought Moore to the area two decades before, under the direction of Jefferies Wyman. According to archeologists, the Orange people used it between 2000 and 500 BC and the St. Johns tribe between 500 and 1500 AD.

Moore and his two colleagues shook hands with the Mansfields and left the camp well-fed. “Goodbye, boys, come again next year,” the captain said. They rowed back to their steamship and continued their voyage and excavation of the mound.

It’s unclear what happened to the Mansfields in the years that followed. I’ve been unable to find a record of their graves nor official land ownership. It seems they were merely squatters since the Bureau of Land Management has no record of a grant or purchase.

A large herd of cattle lived on Mansfield’s Island in 1899. That October, a hurricane nearly wiped it off the map. The Florida Times-Union archives report:

“A crowd of about twenty men went last week to move cattle off Mansfield Island on the east side of Lake Harney. Over one hundred and fifty head were lightered off. One lighter turned over, drowning seventeen head. The water is the highest known in twenty years. Mansfield Island is generally three miles long, but now all is covered with water, except about one acre. The river is still slowly rising.”

The trust of Berenice and Frank Ford owns the land today. It is used primarily for hunting and cattle crazing, with a small private airstrip on the island’s north side. A narrow bridge of Lake Harney Road connects it to the outside world and the hamlet of Pennichaw (to call it a “hamlet” is generous since it doesn’t have a flashing light or a general store). The closest actual towns are Geneva and Osteen.

The End. It’s nice, for once, to have a story that doesn’t end with nature being paved over by development.

References

- The full original story is from Demorest’s Family Magazine, February 1892, by Clarence Bloomfield Moore:

- Bartram Landed on Mansfield/Stone Island

- Life and Work of Clarence Bloomfield Moore

- Volusia County Property Appraiser

- Clarence Bloomfield Moore Wikipedia Page

- Soldiers of Florida in the Seminole Indian, Civil and Spanish-American Wars (book published 1903). The story in the magazine does not mention Mansfield’s first name; it only calls him “captain.” However, only one “Mansfield” appears on the soldier rosters of both wars, which is how I determined he is most likely “William H.” I could not locate him in any Census or other records. I estimate he was born around 1835.

- Civil War Florida 7th infantry soldier list

- Seminole War Florida soldier list

This post is 1045 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.