Juneteenth in Bealsville: Freedom’s Fertile Ground

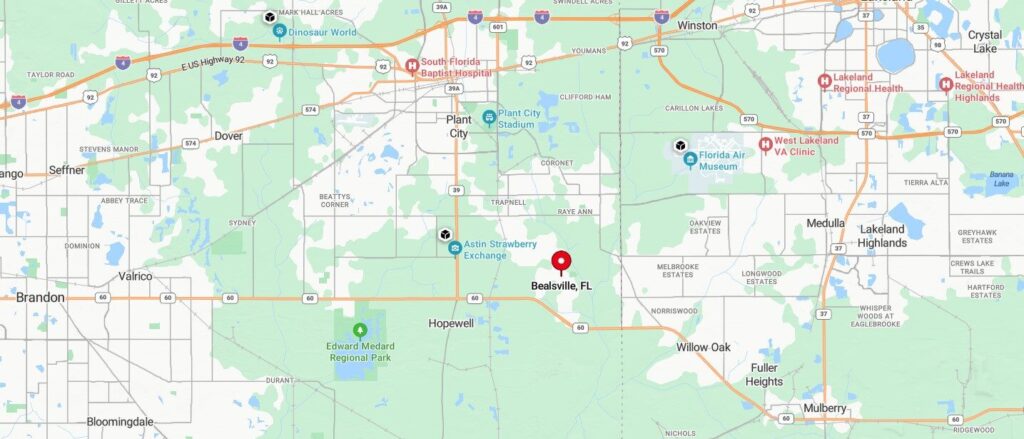

Juneteenth, the annual commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States, holds a unique significance in the fields near Plant City. A story of resilience, hope, and the unshakeable dream of freedom unfolded in this corner of pioneer Florida.

During the 1840s and 1850s, dozens of white homesteaders arrived in eastern Hillsborough County. They brought with them a system built on forced labor–enslaved men, women, and children who toiled the land. Mostly, these were not large plantation owners but small-time farmers with a few slaves hoping to gain prosperity in the newly Seminole-free territory. The primary agriculture at that time was cattle, cotton, and vegetables. Citrus and strawberries, which the area became known for, were a few decades away.

Then, in a transformative moment, news of emancipation reached the enslaved workers on the fields around Hopewell, a tiny agricultural settlement five miles south of Plant City. The weight of their bondage was replaced by an eruption of joyous shouts. The liberated workers threw their hands into the air and tossed farming implements to the ground. They celebrated not just the end of an era but the boundless possibilities that lay ahead.

They were keenly aware of the power of land ownership in America and envisioned a future of self-reliance. They dreamt of working in their own fields someday.

One plantation owner, Sarah Turner Howell (1818-1882), proved instrumental in their journey. Sarah had eight children with her husband, Joseph. They were one of the first white families to settle around Plant City in 1839, a time when Seminoles still regularly clashed with whites in the area. The Howells became relatively prosperous: they owned 1,360 head of cattle and three slaves (Peter, Spencer, and Nancy). Sarah was widowed at 43 when her husband died of pneumonia in 1862.

After emancipation was announced, Sarah had compassion for her newly freed neighbors. She recognized their aspirations and offered them a temporary haven on her land until they could secure their own. Howell provided twelve former enslaved families with the resources (horses, mules, hoes, and plows) to clear and cultivate their own farms. It was a glimmer of humanity amidst the darkness of slavery and prejudice.

By December 24th, 1865, less than a year after emancipation, these twelve families had transformed their dreams into reality. Leaving Howell’s plantation, they established their own town, initially called Howell’s Creek, in her honor. It was later called Alafia (for a nearby river) until it was renamed Bealsville in 1923 in honor of a local hero, Alfred Beal (1859-1948).

The road to land ownership, however, was far from easy. The Homestead Act of 1862 presented significant hurdles in securing a title on up to 160 acres. It had strict requirements for building a dwelling, living on it for five years, and improving a percentage of the land to produce crops. There were filing fees, distant travel to land offices in Tallahassee or Gainesville, navigating complex paperwork, and gathering testimony from reputable witnesses. Nationally, only 15% of Black applications were successful in receiving their land grants.

Despite these challenges, the Bealsville residents persevered and were exceptional in their success. At least a dozen Bealsville families secured 40–160-acre tracts. For those who did not receive a grant, residents pooled resources to purchase land to ensure every family secured a plot. Through tireless work and unwavering determination, many expanded their holdings over time, turning them into thriving farms that sustained generations.

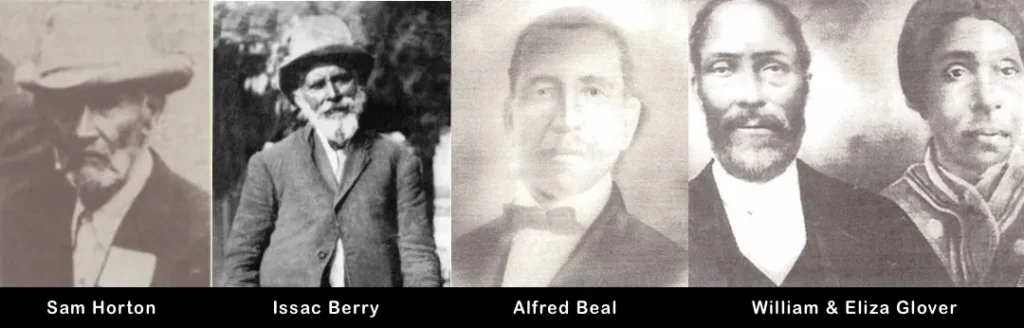

Locals recognize the founding families as Peter Dexter, Bryant and Sam Horton, Roger Smith, Robert Story, Isaac Berry, Mills Holloman, Mary Reddick, Jerry Stephens, Sam McKinney, Neptune Henry (Hendry), Steven Allen and Abe Seconger (with various alternate spellings).

Alfred Beal, the town’s namesake, was Mary Reddick’s son. His mother was brought to Florida from the Caribbean. Alfred’s father was white plantation overseer Frank Beal of Bartow. Alfred married Esther Horton, daughter of another founding family.

The Glovers (William and Eliza) were also important to the town’s development. In 1933, they donated ten acres for a new school in Bealsville, named Glover School in their honor. It was in operation from 1933 until 1980. It is the primary landmark in the town today and serves as a community center.

Though he only had a second-grade education, Alfred Beal was an excellent farmer and a quick study with his real estate investments. He was one of the first in the area to plant citrus groves and became quite wealthy. He donated the land for Antioch Church, cemetery, and early schoolhouse.

Beal was instrumental in helping many families hold on to their land after a series of crop failures and freezes. When many lost their land to foreclosure, he acquired as much of it as possible to allow the families to stay on their property. He sold it back to them once they were back on their feet.

The Great Depression was a trying time for the entire nation; Bealsville was no exception. But these farmers held on to their estates.

Even today, descendants of those original settlers still call Bealsville home and take great pride in their ancestrial property and heritage. Their presence embodies the legacy of their forefathers’ relentless pursuit of liberty and self-reliance. It powerfully reminds us of their remarkable agricultural skills and unwavering work ethic.

The story of Bealsville is a testament to the enduring human spirit, Juneteenth’s transformative power, and the quest for a life built on freedom and self-determination.

Read more about Bealsville settlers

Some homesteaders at Bealsville were part of a short-lived colony in Highlands County that became known historically (by white settlers) as “Niggertown Knoll.” It appeared on maps until the 1990s. Read their story…

Sources

- Slave descendants recall youth in Black settlement of Bealsville (Lakeland Ledger)

- Census Records on Family Search

- Cemetery records on FindAGrave: Antioch Cemetery, Pinehill Cemetery, Shiloh Cemetery (Howells), Wildwood Cemetery (Francis Beal)

- Historical Marker Placed in Bealsville (Tampa Bay Online)

- ABC Action News Covers Bealsville, FL (YouTube)

- Bealsville Florida: Successful Rural Town (YouTube)

- Bealsville Community Site

- Bealsville: A Florida Story of Drive and Determination

- Recognizing Dr. Sam Horton at House of Representatives meeting

- Glover School history

- African Americans on the Tampa Bay Frontier, Book by Canter Brown

- Historical Marker Database: Bealsville and Glover School

- Other records from GenWeb and other PDFs that are now offline 🙁

Land Ownership Records

- Issac Berry – 80 acres in 1889

- Sam Horton – 40 acres in 1892

- Bryant Horton – 80 acres in 1885

- Alfred Beal – 160 acres in 1893

- Rodger Smith – 80 acres in 1885

- Mills Holloman – 80 acres in 1883

- Mills Holloman – 160 acres in 1892

- William Glover received land in Township 29S, Range 22E