Jasmine Theater of Altamonte Springs

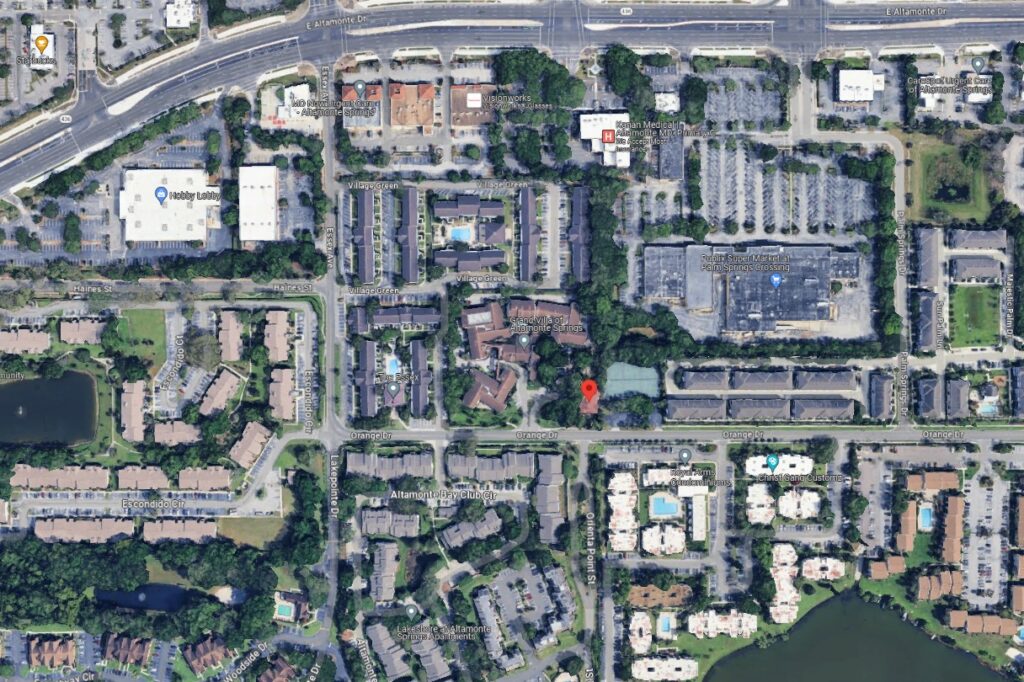

You’d never guess it today, but this modest residence was once the hub of social activity in the early town. It is now barely noticable among its large neighbors, which include apartments, a retirement home, and a shopping complex. But there, nestled beside a tennis court, is one of the last remaining historic buildings in Altamonte Springs.

In 1913, Charles Delmere Haines, a prominent and affluent congressman from New York, made Altamonte Springs his new home. As the town’s most celebrated resident, Haines left a lasting legacy with his vast estate that spanned hundreds of acres of lush ferneries and thriving orange groves, gracefully wrapping around the northern and western shores of Lake Orienta.

His estate became a hub of social and political activity, where he regularly entertained distinguished guests, including the former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan. Haines’ presence and hospitality transformed Altamonte Springs into a vibrant epicenter of high society and political discourse.

In 1920, Haines built “The Jasmine” as a private clubhouse to host meetings and parties for his important guests. It was surrounded by 75 acres of Haines’ orange grove along the appropriately named Orange Drive in Altamonte Springs. At the time, it was the main highway heading west toward Apopka.

A year later, Haines opened the venue to the public as a theater. He invited both tourists and visitors from surrounding towns. Haines designated certain nights for each town, so Tuesdays might be “Winter Park Night.”

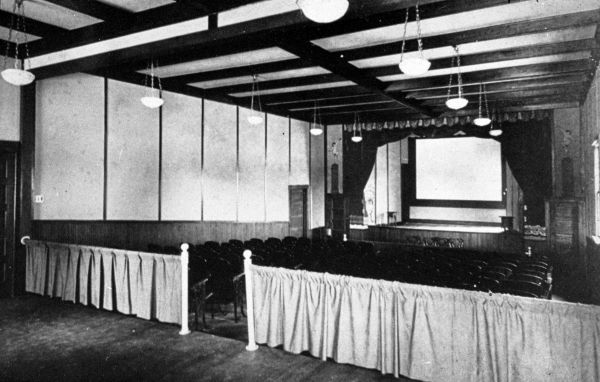

According to newspaper reports from the era, the main hall had room for 120 chairs and packed in up to 150 guests. The floor slanted downward toward the stage. Behind the back row were box seats with plush chairs for the VIPs.

The curtained stage was suitable for both live performances and motion pictures. In front was a small orchestra pit. Backstage were dressing rooms for actors. An attached apartment was home to a live-in caretaker of the theater, garden, grove, and grounds.

Cherub statues elegantly straddled either end of the stage. The paneled walls were painted a soft green. Exposed ceiling beams gave it a grand feel, and globe lights extended from the ceiling. They gracefully dimmed as showtime approached.

The lobby had a reception area with a small cocktail lounge served by a bartender. It had an attached kitchen that cooked meals for private dinner parties or light hors d’oeuvres for public nights. The lobby was adorned with fragrant white jasmine flowers, an obvious nod to its name.

Around the theater was a rustic medley of flowers. The Haines Estate, called “The Ferns,” was just across the road. It was essentially an extension of the theater grounds for guests. It had lighted electric pathways (novel at the time) that wound through a beautiful rose garden and down the shore of Lake Orienta.

Haines had a boat landing for his watercraft, including a small steamship and a large houseboat called “The Kathryn,” named for his wife. He loved to cruise guests around the large lake.

Various Forms of Entertainment

Every type of show you can imagine was hosted here. There were Vaudeville-style variety shows, choirs, orchestras, plays, and silent and “talkie” movies. A live orchestra would often perform to add ambiance to the movie or performance.

For example, one night in 1922 had a full roster of entertainment:

- The Orange City Orchestra from Volusia County opened

- Singing and guitar by “Blind Caruso,” a local black musician who was led in by a guide and smiled at the audience despite his disability

- A two-real Century comedy

- Music by the “Jasmine Chorus,” twelve black singers who performed “old plantation songs.”

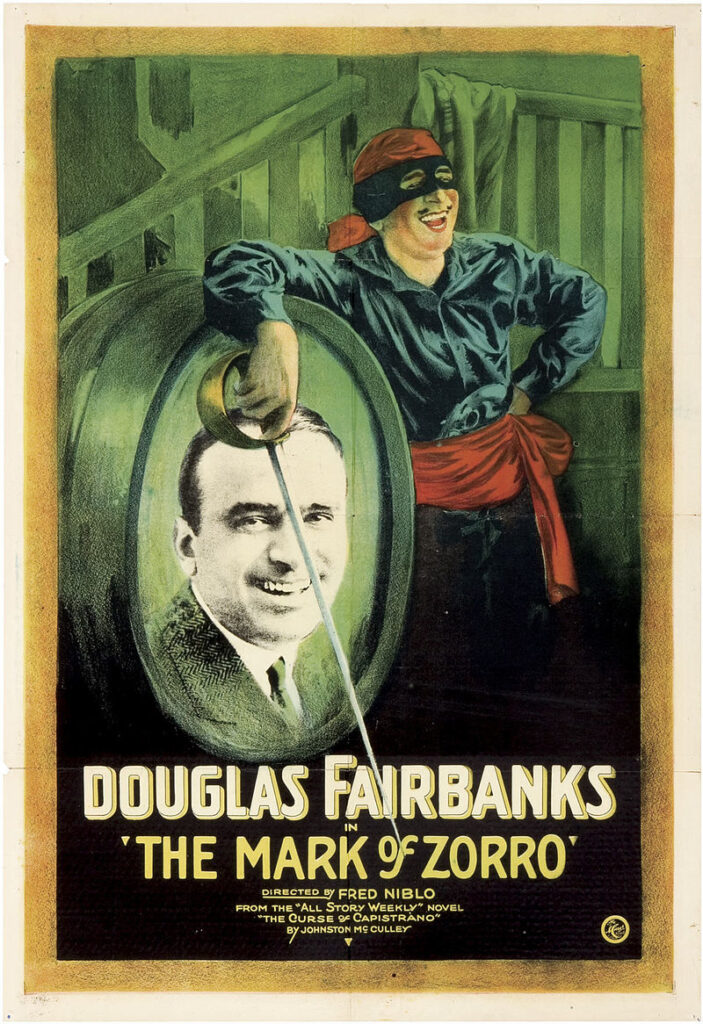

- Feature presentation: the film “The Mark of Zarro” with Douglas Fairbanks

Out-of-state performers popped by as guests. Others were regular talent, such as the Lyman Twins (Howard and Herbert) and Emma Abbott Lyman (wife of Howard). After a long stint on stage and film, they retired to the area as talented actors and musicians.

In 1924, Lyman School opened and was named for Howard after his sudden death in a diving accident earlier that year.

Theater Closes, Visions of a Press Resort

However, the millionaire’s attention span was fleeting. After several years of hosting events, Haines became infatuated with a new idea.

He believed journalism was essential to America’s Democracy and wanted to leave a lasting legacy to the “fourth branch of government.” Haines wanted Altamonte Springs to be home to a resort dedicated to active and retired members of the press.

He deeded the theater and 75 acres surrounding it to the newly formed corporation, “The Florida National Home for Newspapermen,” affiliated with the International Press Association. Haines additionally donated $100,000 to the cause and suggested another 100 acres would be donated to the group upon his death.

The resort was to be an expansive estate with lodging for hundreds of visiting writers. It aimed to raise an endowment of $15,000,000 to seed its eternal existence. However, the project never materialized. Haines’ health began to suffer in the latter half of the 20s.

Property Sold

After Haines died in 1929, the newspapermen’s organization sold off the properties. It was purchased by Rudolph and Maple Haas, who began its conversion to a private residence. They never moved in, though, and the house sat vacant throughout the Great Depression.

In the late 1930s, Chester Fosgate, who had a large packinghouse in Forest City, purchased the home and surrounding groves. The Altamonte landmark quickly deteriorated. By 1940, Fosgate planned to mow it down to plant more groves.

The Bradford Family Moves In

Robert Bradford was a plant manager for Fosgate. He and his wife, Grace, loved the beautiful estate and its history. They begged Fosgate not to tear it down. Their persistence paid off, and the citrus mogul agreed to sell it to them in 1940.

At that point, the Bradford’s friends and family thought they were nuts. The roof was literally about to collapse. It needed expensive renovations just to keep its four walls standing, let alone to make it liveable as a home.

They more than succeeded! They replaced the roof, leveled the floor, removed the stage, and partitioned rooms. They kept the vaulted ceilings. Bit by bit, they made over every corner of the house and added a back porch.

The former stage became the master bedroom, and the dressing room had an en suite bathroom. The caretaker’s apartment became the bedroom of their son, Robbie. The lobby became a living room, the VIP seats became a dining room, and the main theater seating became their family room.

For a few decades, the road in front of the home remained on the main highway. As the town grew, it got progressively busier and disturbed their quaint oasis. The family was thankful when Highway 436 was constructed to the north, downgrading their frontage back to a country road.

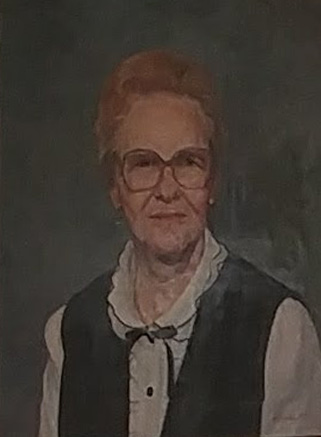

The family lived in The Jasmine for almost fifty years until Grace died in 1989.

Grace Bradford’s Legacy

It deserves to be noted that The Jasmine was Grace Bradford’s first foray into historic preservation, but it would not be her last. Her contributions to local history have not been celebrated nearly enough. She and her husband are responsible for first-hand saving at least 14 historic properties, including the Herculean effort to save the Longwood Inn.

Grace was one of the very early members of the Longwood Historic Society, who played a pivotal role in moving the Bradlee-McIntyre House and Inside-Outside House from Altamonte Springs to Longwood (they were to be destroyed). She even donated the lot where the Bradlee now sits.

The 1990s through Today

Not long after Grace died, the redevelopment came knocking, and the treasure was almost lost. The new owner, Dick Ostrander, offered to donate the building to the City in 1992 — on the condition they move it somewhere else. He gave 90 days for it to be moved or torn down. The funding never came, but thankfully, public outcry convinced Ostrander to relent.

Some suggested it would make an excellent museum or headquarters for the Altamonte Springs Historical Society. That was never more than idle talk, and nothing materialized.

Since then, it has remained in use as a private home. It expanded to four bedrooms and 2,659 square feet of living space. The main house has two bedrooms. Two separate apartment units were added to the rear. The backyard features generous entertaining space, brick-paved walkways, a garden, and multiple outbuildings. It last sold in 2002 for $405,000.

The cool thing is that despite the significant conversion from a public venue to a private home, the original character and architectural features of the original theater can still be identified. For example, the exposed rafters and similar lighting elements take you straight back with a bit of imagination.

Let’s hope this little gem can continue to be preserved!

This post is 603 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.