Fern Park, Florida and the Largest Industry Under One Roof

Fern cultivation gave rise to a new town with the Haines, Barnett, Casselberry and Vaughn families its royal court.

Before Seminole County was created in 1913, the area that is today known as Casselberry was referred to as the Concord Settlement. I dove into the early pioneers of that village in a previous article.

That community mostly dried up in the 1880s, after its church burned and the railroad stopped at Longwood and Altamonte instead. Any remaining hope for Concord’s long term development was likely killed off (with all the citrus) during the great freeze of 1894–1895.

Since orange groves take about seven years to become productive, it was into the new century before the citrus industry began to come back online. But it did eventually recover, and once again came to reign as the section’s primary industry by the 1910s.

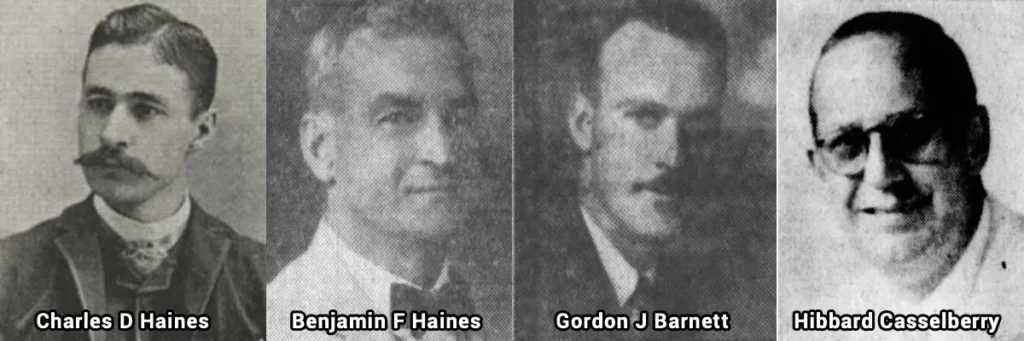

At the same time a steady stream of wealthy tourists from the Boston began to frequent Altamonte Springs, often staying December through April. Among the winter guests was former New York congressman Charles Delemere Haines, who decided to make Altamonte Springs his full time home in 1911. His estate west of Lake Orienta was as stunning as it was expansive.

On this thousand-acre property, which he shared with his brother-in-law and business manager George Kingsley, the railroad entrepreneur experimented with cultivation of various crops. Asparagus plumosus ultimately became their central product, which were marketed as “ferns” (though technically they are in the lily family).

These bristly plants are grown as ornamentals, often a foundation of floral bouquets in northern markets. They were a welcome alternative to citrus and boon to the economy after freezes — because ferns can go from seed to harvest in less than a year.

During cold snaps, growers successfully salvaged the frost-sensitive crops by burning thousands of gallons of oil. Harvests were multiple times a year, with the biggest demand ramping up around Easter and Christmas. Afterward, the vast acreage was mowed down almost to the root. This aggressive pruning assured the highest quality of feathery fronds would spring up.

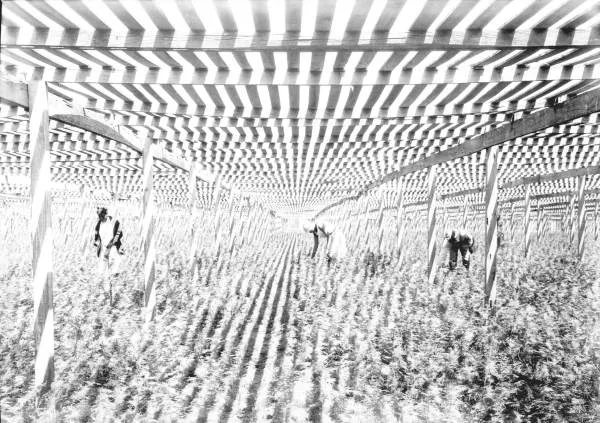

Since they can not survive in direct sun, fern cultivation requires the construction of slat shed structures. Single ferneries could span 65 acres, so we are talking massive footprints of shade houses. Locally Haines’ Royal Fernery was styled as “the largest industry under one roof.” Its 3,500,000 lengths of lath laid end-to-end would stretch from Altamonte to New York and back.

By 1920, the Royal Fernery had birthed an entire company town southwest of Altamonte Springs. Its facilities included 44 shotgun houses that provided free rent for its (mostly black) workers, a self-contained electrical and water system, a theater, a store, a church, and a school.

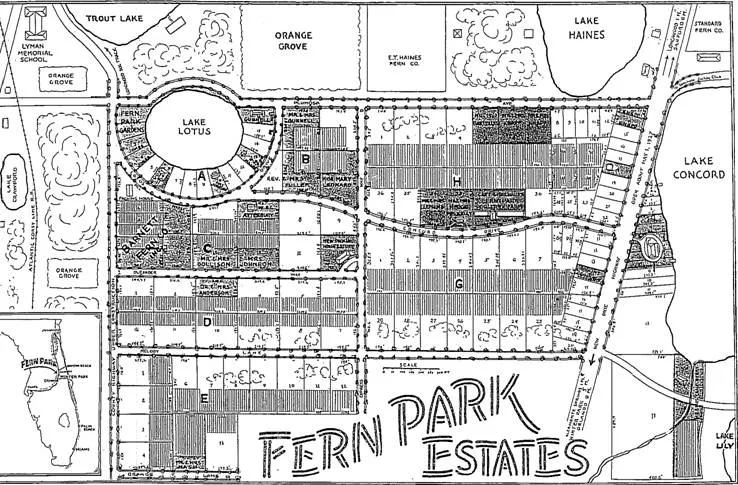

With that success and increasing demand, the Haines family expanded by purchasing 160 acres along Lake Ellen in 1921, called the Haines Fernery. His brother, Elmer T. Haines (mayor of newly incorporated Altamonte Springs) managed that operation. They added additional acreage north of Lake Concord and branded the Standard Fern Company under the control of nephew Benjamin F. Haines.

Gordon Barnett, a friend of the Haines family, decided to jump into the fernery business himself. At the time, Barnett was editor of the Winter Garden Herald, where he saw the fern business blossoming around the Lake Apopka region. Barnett’s father was Presbyterian minister Augustus Barnett, an English immigrant and a prominent local businessman in his own right.

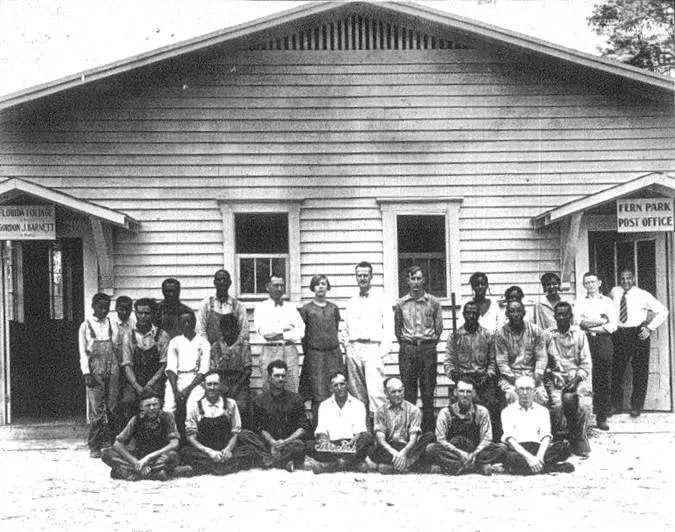

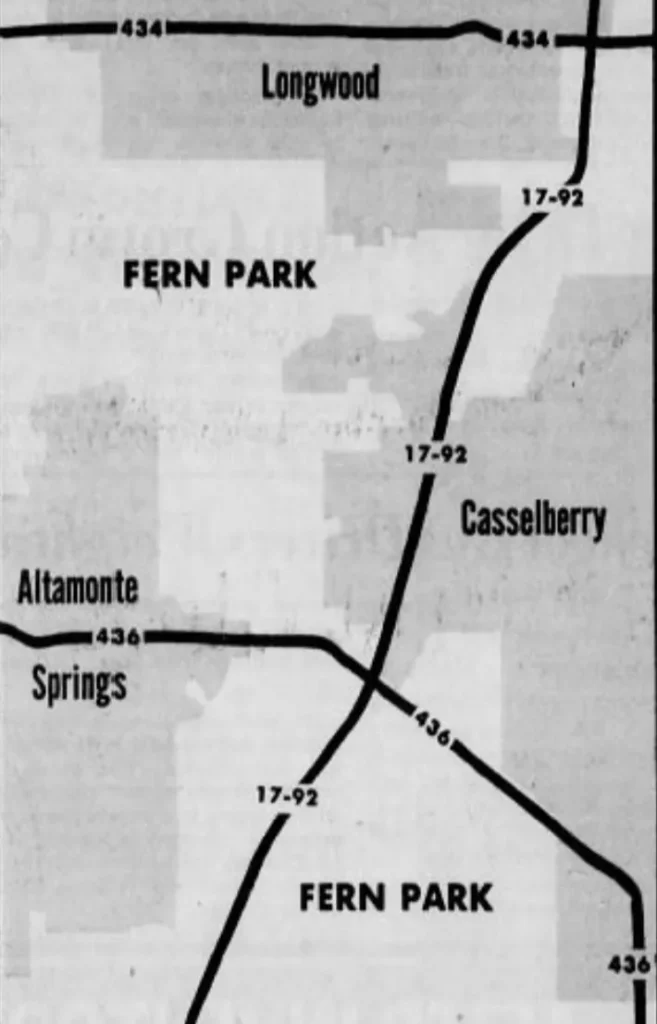

The Barnett family purchased a swath of land between Lake Lotus and Lake Concord, which Gordon platted as Fern Park in 1923. The Barnett Fern Company opened for business in 1925, with headquarters at what is now the corner of Oleander Way and Anchor Road.

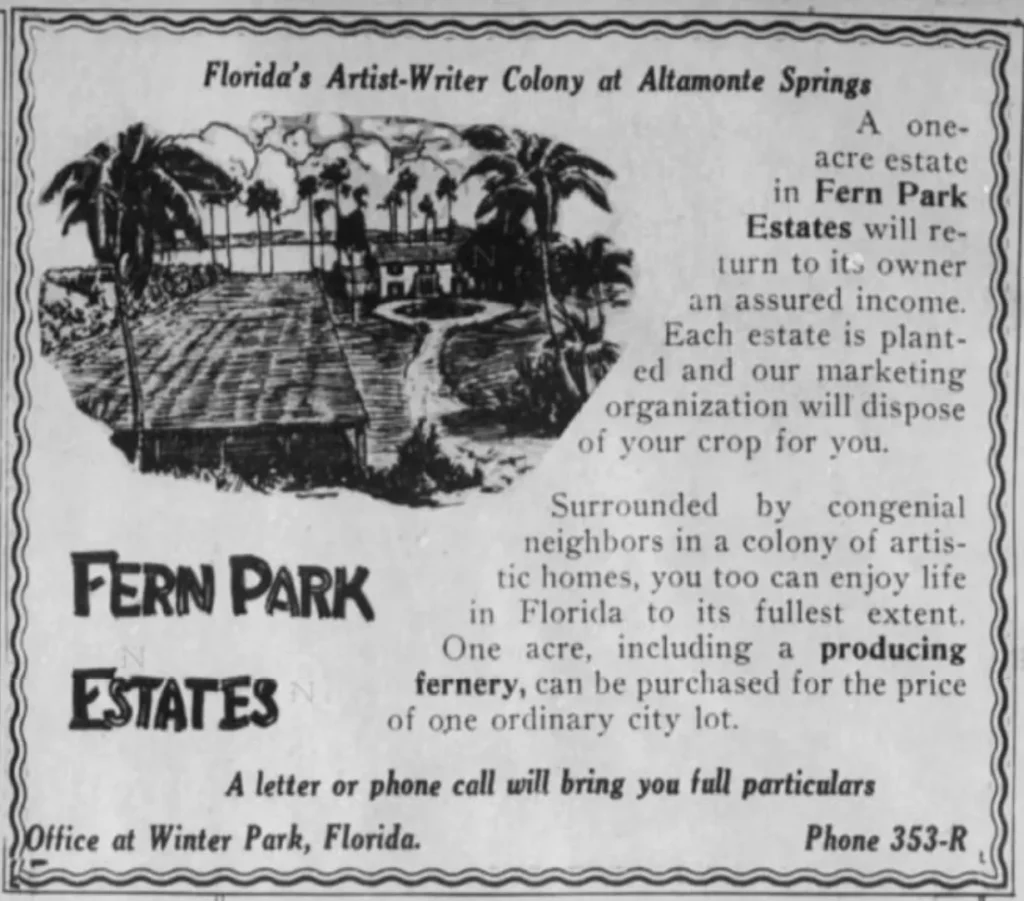

With the Great Florida Land Boom in full blast, Barnett decided to do something different. Instead of cultivating all of the land himself, which required a massive amount of capital to build the shade houses, he marketed the area to home buyers as Fern Park Estates.

Each one-acre lot included not only a lovely modern home but also a mini fernery behind it. The company assisted homeowners with cultivation, marketing, and sales. With this arrangement, home buyers had a ready-made source of income that also served to finance Barnett’s expansion.

Around that time, Chicago residents Hibbard and Mary Leonard Casselberry were vacationing in Winter Park in 1926 to visit Mary’s aunt (who she was named after). The couple and their two young children fell in love with the beautiful region full of lovely lakes and decided to make it home.

Hibbard later told a reporter: “We came to Florida to spend two weeks. We liked it and decided to spend two months. Then we decided to stay a year, and somehow that year isn’t up yet.”

He opened a florist shop on Park Avenue and got to know Gordon Barnett. Learning about the New Dixie Highway being constructed along the eastern boundary of the plat (State Road 3, which would later become US Highway 17–92), Casselberry knew Barnett was on to a huge opportunity.

The wealthy midwesterner worked for Barnett as a Fern Park Estates sales agent in 1927. Then, indeed, a conflict of interest, he purchased 3,000 acres of land south and east of Barnett’s Fern Park Estates. The plot spanned both sides of the new highway and encompassed a dozen lakes.

Casselberry sold his small nursery on the southwestern end of Lake Orienta to the Hattaway family and decided to focus solely on the Fern Park project. Hibbard founded the Winter Park Fern Company and followed the Barnett model by subdividing much of the land for home buyers.

The two men became partners in the Winter Park Fernery venture for a time, but that affiliation was short-lived. Into the headwinds of declining sales in the Great Depression, the two men divorced their operations by 1933.

By that time, Fern Park had become a booming suburb, a halfway point on the straight-shot road between Sanford and Orlando. Though unincorporated, Fern Park was far more developed than its municipal neighbors, Longwood and Altamonte Springs.

The Dixie Highway through Fern Park was lined with agriculture (ferneries, nurseries, citrus groves, and poultry) and small commercial buildings, including a candy company, antique shop, and tea room. The town was granted a post office in 1928 adjacent to the Barnett Packing House, which moved to an upgraded facility along State Road 3 (17–92) in 1930.

Months before the bottom fell out of the stock market in 1929, Charles Haines died. His nephew Benjamin took over many of the family’s various interests in the fern business and became the mayor of Altamonte Springs in 1932.

However, with depressed northern markets, demand for ornamental ferns weakened, and the Haines empire began to decline. Benjamin sold off the Royal Fern Company in Altamonte Springs to longtime friend Arthur Crowley of Medford, Massachusetts (a town Benjamin had previously been mayor for several terms), but he still stayed involved in the business.

Frank Vaughn, a recent transplant from Kansas, purchased the Haines-owned Standard Fernery in 1934. For many decades after, Vaughn became the third of the Fern Park power brokers — with Casselberry and Barnett — and one of the town’s largest employers. This fernery and packing house were where the Home Depot and Publix plazas are today.

In 1936, the ferneries successfully navigated through the worst of the Great Depression. Gordon Barnett was riding high as one of Seminole County’s most beloved citizens. He parlayed that into a winning campaign and Florida House of Representatives election.

During the 1937 legislative session in Tallahassee, Barnett introduced a measure to incorporate the town of Fern Park. He boldly proclaimed that the initiative had the full support of the population, which sounded legit since Representative Barnett was the town founder and popularly elected congressman. It passed the House, was rubber-stamped by the Senate, and headed for the governor’s desk to sign.

Only it wasn’t true. The soon-to-be annexed citizens of the new municipality were vehemently against it. The clock was ticking.

Fern Park resident R. C. Nash frantically telegraphed Governor Fred P. Cone, Senator J. J. Parrish (Titusville), and Representative H. J. Lehmann (Sanford), asking them to stop its passage. Meanwhile, four carloads full of locals headed for Tallahassee to fend it off personally. They carried a petition opposing incorporation, signed by 75% of registered voters.

Governor Cone assured the anxious petitioners he would not sign it, and as soon as the Senate reopened, they recalled the bill. Gordon Barnett received a tongue-lashing from his travel-weary constituents and relented.

That same day, he announced that he was “unhesitatingly” withdrawing the bill. However, it was apparent he had no choice! The attempt blew up in his face, and the blunder would be hard to live down.

The proposed charter would have created a three-member town council, casting more doubt on Barnett’s supposed benevolence. It was to install the initial members for up to four years without an election; they were all close friends with Barnett (including an immediate family member). Locals cried out “taxation without representation,” and his credibility was toast.

It probably goes without saying, but Barnett lost his reelection campaign in 1938. Then, in 1939, the three buildings at the Barnett Fernery were destroyed by a massive fire. The circumstances were considered suspicious. Perhaps it was arson by angry locals? No cause or suspect ever surfaced.

Of course, this is not the end of the story; it is just the beginning. If we ended here, the reader might wonder why Fern Park is described as the stretch of highway that is clearly Casselberry today.

That brings us to 1940 and the seeds of a war about to erupt. No, not the one over in Nazi Germany, but right here in South Seminole County.

The anger over Gordon Barnett’s proposed incorporation and levying taxes in Fern Park melded with the unquenchable ambition of Hibbard Casselberry, sparked a coup d’etat that created the town of Casselberry and a bitter feud that spanned decades over each town’s right to exist.

But, my friends, for that story, read on in part two…

This post is 2555 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.