Cross Florida Barge Canal: A Shortcut That Never Was

The Cross Florida Barge Canal was an ambitious and ultimately unfulfilled project to carve a watery path across the state’s midsection, connecting the Atlantic Ocean with the Gulf of Mexico.

The dream of a cross-Florida shortcut has a surprisingly long lineage. As early as the 16th century, Spanish colonizer Pedro Menendez de Avilés, frustrated by the lengthy journey around the peninsula, reportedly remarked on the potential benefits of a canal. However, the technology and resources for such a feat weren’t available then.

Fast forward to the 19th century, and the canal concept resurfaced. The burgeoning American economy saw Florida as a treasure trove of resources, and a canal promised to streamline the transport of timber and cotton between the state’s coasts. Throughout the 1800s, several surveys were conducted, but the sheer scale and cost of the project proved prohibitive.

New Deal Provides Initial Funding

The 20th century, however, ushered in a new era. The Great Depression saw the Cross Florida Barge Canal resurrected as a New Deal jobs program. President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself declared his belief in the project’s ability to stimulate the economy and create jobs for the unemployed. In 1935, with a flicker of hope, construction sputtered to life. The Florida Canal Authority was created and FDR budgeted $5 million of the estimated $143M project.

During this period, over 5000 acres of land were cleared for the project. 13 million cubic yards of material was excavated and bridge piers were constructed near Ocala.

However, the 1930s proved a difficult time for the canal. Funding was a constant struggle, with rival politicians challenging the idea. The initial allocation soon ran dry, and despite some early progress, construction largely stalled by the end of the decade. World War II further complicated matters, diverting resources and manpower away from the project.

The 1940s saw the Cross Florida Barge Canal relegated to the back burner. While the war raged on, the dream of a watery shortcut remained dormant. Funding remained scarce, and with no significant progress made, the project became a lingering reminder of unfulfilled ambitions.

Construction Starts Again

The canal dream remained dormant for decades before re-emerging in the 1960s. This time, national security concerns fueled the project. Amid the growing Russian influence in Cuba, Secretary of the Army Stanley Resor stated his belief in the canal’s value to the national defense transportation system.

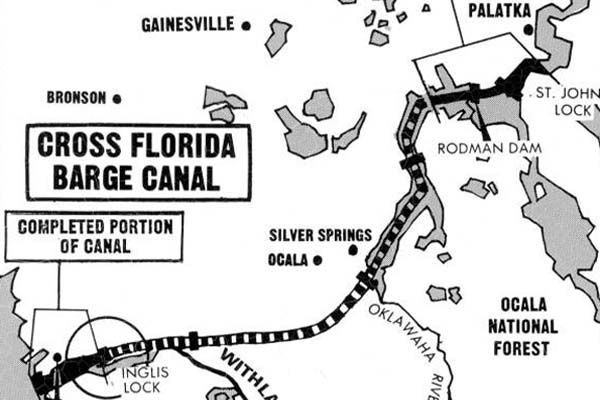

In a grand ceremony held in Palatka, Florida, in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson himself presided over the official groundbreaking. Johnson ceremoniously triggered the explosion to begin the construction in earnest, with plans for a 171-mile (275 km) waterway.

Construction during the 1960s saw excavation and dredging along the planned route of the canal, from the St. Johns River near Palatka to the Gulf of Mexico near Yankeetown. The work included building locks and dams to manage water levels along the canal and facilitate navigation for barges and other vessels.

The Rise of Environmental Concerns

However, even as construction progressed, a new voice began to rise in opposition – the environmental movement. The 1960s saw a growing awareness of the importance of ecological conservation. Public attention turned to the potential environmental damage the canal could inflict.

- Endangered Species and Ecosystems: The canal route cuts through pristine wetlands, which are vital habitats for numerous species, some of which are endangered. Environmentalists pointed out the disruption this would cause to delicate ecosystems.

- Water Flow Disruption: Concerns about the impact on Florida’s intricate water system were raised. The canal could disrupt natural water flow patterns and potentially harm freshwater springs.

- Marjorie Harris Carr and the Fight Back: Environmental activist Marjorie Harris Carr emerged as a vocal opponent of the project. She rallied public support and challenged the canal’s benefits, highlighting the environmental costs.

Public Opinion Shifts and the Project’s Demise

By the early 1970s, public opinion had significantly shifted. Environmental concerns trumped the arguments for national security and economic benefits. Legal challenges mounted, and the environmental impact became a major sticking point.

In 1971, President Richard Nixon officially halted construction, facing mounting pressure and a changing tide of public opinion. The project was deemed too environmentally destructive to continue.

Partial Construction

Around 28% of the canal was completed, translating to roughly 48 miles (77 km). These completed sections included:

- A central canal section cutting across Florida, connecting the St. Johns River to the Ocklawaha River.

- Parts of the route along the Ocklawaha River to straighten and deepen parts of its path.

- A small section near the Gulf of Mexico endpoint, reaching Lake Ocklawaha (created by the Rodman Dam)

Town of Santos Destroyed

Founded in the late 19th century, Santos was a hub for the citrus industry. It was located about six miles south of Ocala and benefited from its strategic location along the railroad.

It developed as a predominantly African American community. It had many homes, businesses, and a vibrant social life centered around its close-knit population. Santos boasted schools, churches, juke joints, and other amenities that supported its residents.

In the 1960s, the canal’s path was planned to cut directly through Santos. Imminent domain allowed the government to claim the property, leading to the forced relocation of its residents and the demolition of homes and businesses. Many families who had lived in Santos for generations were displaced, reportedly forced to sell at below market value. The community’s infrastructure was dismantled to make way for the canal’s development, which ultimately never came.

While the canal’s most severe environmental consequences were avoided, the damage to communities like Santos was irreversible. The once-thriving town was left abandoned, its former residents scattered, and its buildings demolished or left to decay.

Legacy: A Shortcut Unbuilt, A Greenway Established

The project was not officially killed by Congress until 1990. After that, the lands were turned over to the State of Florida for preservation.

While only part of the canal was ever completed, the legacy of the Cross Florida Barge Canal lives on. The unfinished sections transformed into stagnant pools, but this environmental scar ultimately led to a positive outcome. The Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway, a 110-mile long linear park, now occupies the land designated for the canal. Hikers, bikers, and paddlers can explore this unique greenway, a constant reminder of a project that, thankfully, never came to fruition.

The Cross Florida Barge Canal’s story serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting the importance of careful environmental impact assessment before embarking on large-scale development projects.

This post is 608 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.