Ginger Ale Springs

In the Seminole County woods, lost in time is an unmarked spring with an intriguing past.

Every day, thousands of cars zoom past on nearby Markham Woods Road. Its bubbling brook gurgles only a few hundred feet from Interstate 4 and State Road 434. Hiding off in the woods is a tiny boiling spring. Although unknown even to most lifelong residents, for decades, insiders have called it “Ginger Ale Spring.”

Local legend vaguely claims that it was once harvested for ginger ale bottling but lacks any supporting details. Some suggest that it might all just be an urban legend. It’s not. We’ll pop the top on this local history mystery, but first… we have to go back to the beginning.

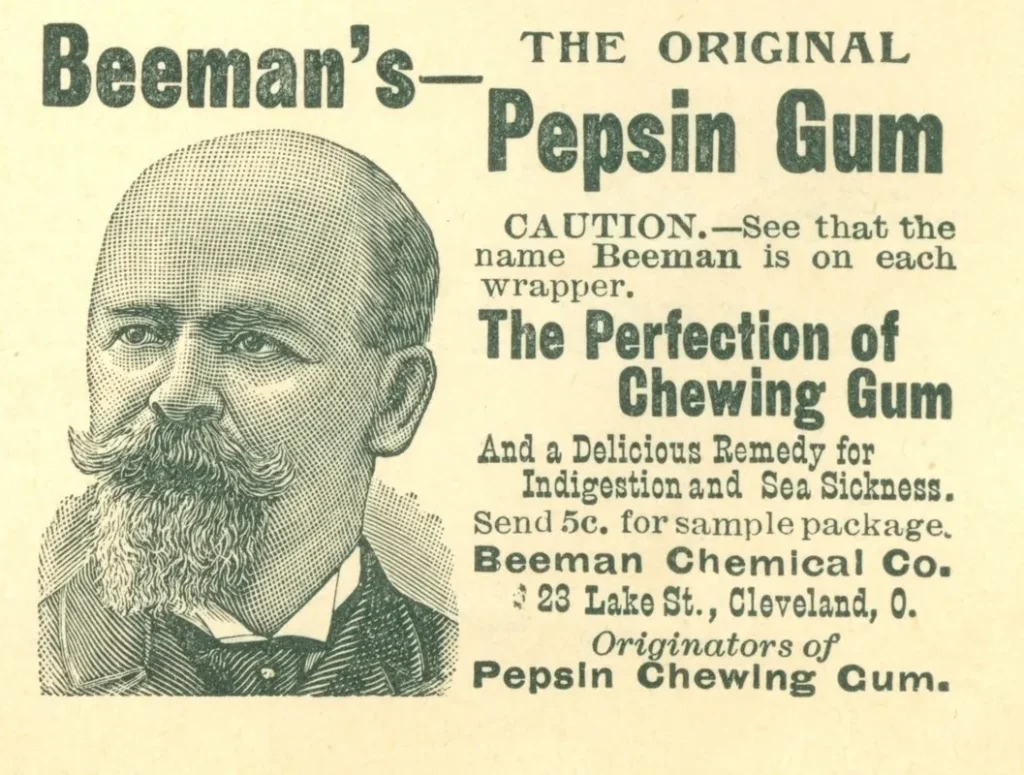

Beeman Gum Fortune

It is 1890. Doctor Edwin Eugene Beeman sits in his lab, wondering what he can do to boost sales of his pepsin powder. Nine years prior, the Cleveland druggist discovered that peptides, a naturally formed stomach enzyme, aided digestion and helped cure an upset stomach.

He learned he could extract the substance from pigs and turn it into powder. The product began to sell at drug stores and hit its stride in 1885 under his startup, the Beeman Chemical Company. Sales were okay, but not out of this world.

Meanwhile, a new gum craze was beginning to catch across the United States. Various materials were used then, but the variety with the most wind in its sales (pun intended) contained a plant material called “chicle,” found in the Yucatan. The big problem was that most gums on the market didn’t taste too great and lost their flavor after a very short time. They also didn’t serve any greater purpose beyond just exercising your jawbone.

At the suggestion of one of his assistants, Dr. Beeman experimented with mixing his pepsin (which had a decent yet unique flavor) with chicle. The results were an unmitigated success, and Beeman Chemical Company’s revenues skyrocketed. In no time, it became a nationally recognized brand and is still an iconic product.

Family Moves to Orlando

Mary Cobb Beeman, the wife of Dr. Beeman, started spending winters near Orlando in the early 1880s to escape chilly Cleveland, Ohio. She purchased a large estate on Lake Sue. During their trips south, she would bring her son, Lester, who was 12 years old on their first trips. Their older son, Harry, decided to move there full-time in 1887; Lester followed him and graduated from Rollins College in 1889.

The brothers prospered in Florida. They invested in real estate, citrus, and ranching. But their wealth and status went through the roof when their dad’s gum company took off! They each built adjacent 40+ acre parcels along Lake Sue with massive homes, along with numerous other properties in the area.

In 1893, Harry purchased the San Juan Hotel in downtown Orlando. It was a three-story, wood-framed building with a dome on top. The property proved a steady and profitable business, despite the coming woes Florida’s agriculture would weather that decade.

In 1899, Dr. Beeman cashed out. He sold the business to a new gum conglomerate called American Chicle. The Beemans were multi-millionaires at a time when a million dollars was a lot grander than it is today! The Orlando area Beemans were well-liked and upstanding socialites. Their renown and influence (and portfolio) grew with each passing year.

Starting in 1901 and for the next two decades, Harry invested in a series of extensive renovations to the San Juan. The hotel grounds expanded both outward and upward.

Over the years, its wood was overlaid with a steel frame, and the hotel went from three to five to eight stories tall. It was fashioned with a veranda and consumed an entire commercial block. It housed a post office, laundromat, multiple restaurants, a barber shop, and more. It was a swanky place!

Lester Buys Palm Spring

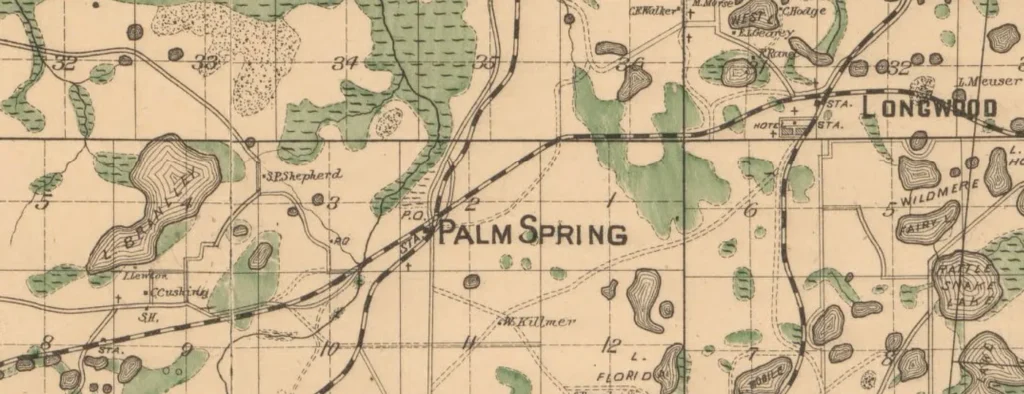

One of Lester’s investments in the mid-1910s (owning it at least by 1916) was a former town site 20 minutes north of Orlando. This once promising hamlet (at I-4 and 434, west of Longwood) was first called Altamont — without an “e” — and later Palm Spring(s) — sometimes plural and sometimes not. Complete with not one but two railroads, a post office, and several stores, it had a population of over 300 by 1890. However, all of that changed after the 1895 freeze. After that, it mostly became a ghost town for decades to come.

However, while it failed as a community, the five springs along the Little Wekiva River had been prized natural treasures since the Native Americans called the area home. They were coveted for recreation and for the supposed healing powers of their waters. After visiting the place, Beeman immediately saw its potential and scooped it up! His parcel was east of the Little Wekiva and included the prominent Palm Spring and a lesser spring—which we’ll get to later.

Note: Hoosier/Sanlando, Shepherd/Starbuck, and Pegasus Springs were not a part of the Beeman property.

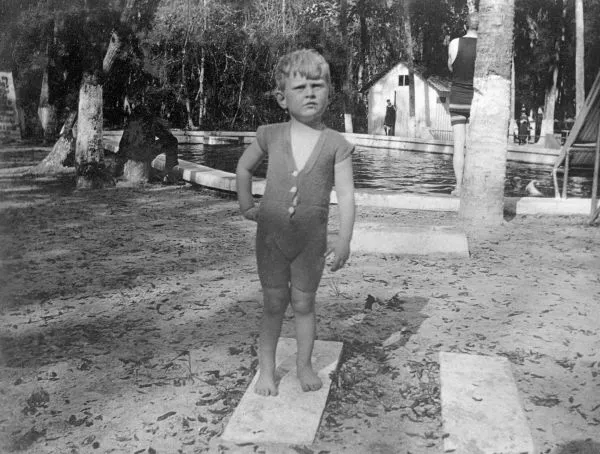

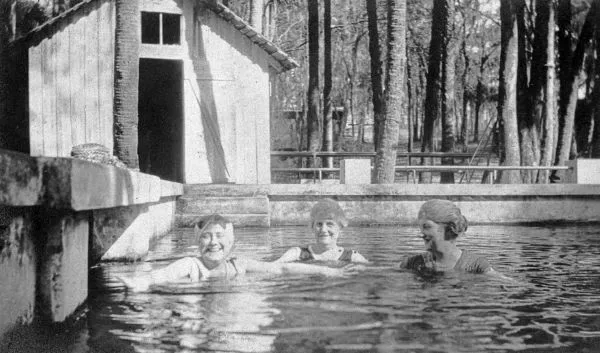

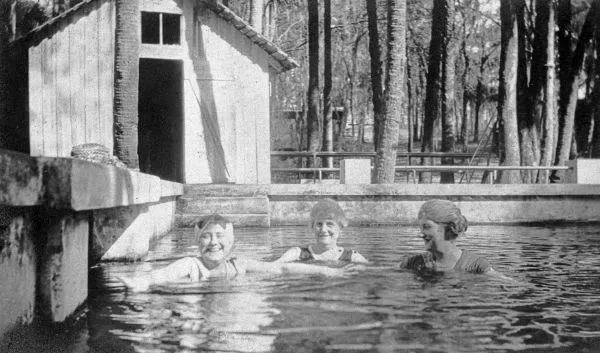

Palm Springs was marketed as a weekend getaway. It was a go-to spot for folks throughout Central Florida for two decades. The cool waters of its rectangular pool hosted company outings, picnics, parties, and just friends goofing off! Lester Beeman added amenities such as a bathhouse, slide, and high dive.

What about the ginger ale???

Things were going pretty well for the Beeman family. They had met success in pretty much anything they tried. The father, Harry Beeman, was president of the Orlando Bank & Trust Company. Lester and his father owned massive neighboring estates in Winter Park. And, in 1923, they signed a deal to lease out the San Juan Hotel for $1.5 million, freeing them up from that management responsibility and opening up other opportunities.

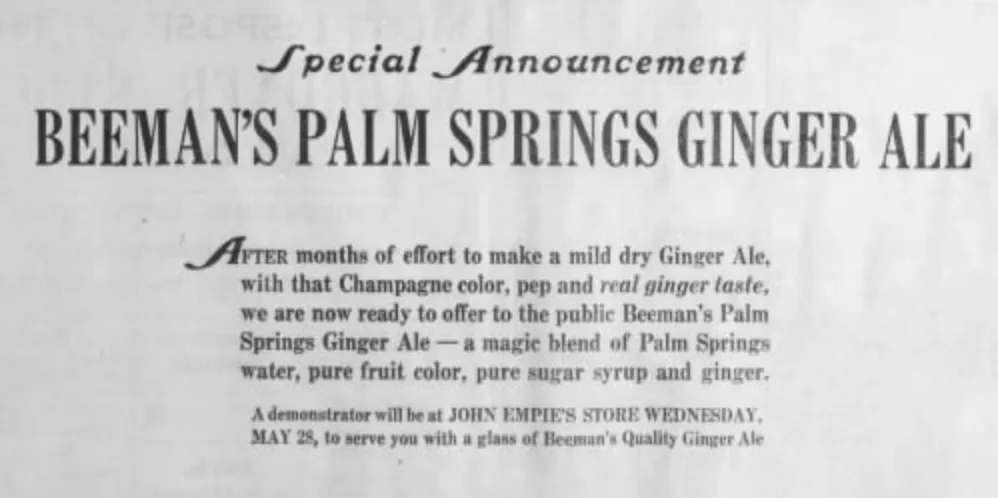

So, on February 9, 1924, the Beeman Investment Company announced in the Orlando Sentinel that it was entering the bottling business. A decade earlier, owners at the next-door Hoosier Spring (later Sanlando Spring) experimented with selling small quantities of their water to local druggists. Sales were sluggish, but the Beemans thought they could do it better.

There was a smaller spring on their property north of the famous recreational spring, “Palm Spring.” The Sentinel declared, “a modern bottling plant has been erected at the spring… is already in operation.”

Near the Orange Belt Railway, north of 434, they built a beverage manufacturing facility and a green-painted collection tub around the spring. The buildings are long gone, but they were probably just uphill from the spring near the roadway and railroad track (now the Seminole-Wekiva Trail).

The beverage company’s headquarters were downtown Orlando at Pine Street and Court Avenue. Harry Beeman and partner E. H. Sutherland promised, ” Its sale will not be confined to Orlando, but a national advertising campaign will make it known throughout the country.”

But their claims did not stop there. “In a short time it is expected it will be in as great demand… as are coca-cola,” the announcement boasted and continued, “… it will shortly be as famous as Beeman’s Pepsin Gum.”

A longer-term roadmap was planned for additional beverages, but for the company’s rookie season, they stuck with two products: Beeman’s Palm Spring Water and Beeman’s Palm Spring Ginger Ale.

Despite the exaggerated braggadocio (arguably not unlike the similar claims on any and all Florida real estate at the time, but I digress), they promptly launched the product and started an advertising campaign.

By March, they were distributing their spring water line. And on May 25, 1924, they announced their ginger ale product was ready for mass consumption. The product was described as “a mild dry Ginger Ale, with that Champagne color, pep, and real ginger taste” with “a magic blend of Palm Springs water, pure fruit color, pure sugar syrup, and ginger.”

The advertising campaign was in full swing for the next six months, albeit with a limited market. There are no signs the product ever received distribution or marketing outside of the modern “I-4 corridor” between Orlando and Tampa.

The water and ginger ale products were carried by most local druggists and independent grocers, as well as emerging chains such as United Markets grocery, with four stores in Orlando alone and 34 total (all in the Tampa Bay and Orlando area).

Palm Spring Ginger Ale was sold for 15–19 cents per pint. The price was competitive with other national brands, but it simply did not catch on as they had hoped. Less than a year later, the plant’s operation completely stopped. No advertisements for the product appeared in newspapers after December 1924.

After the beverage’s non-coca-cola-like reception, Lester Beeman sold his Palm Springs property to Frank Snyde in March 1925, at the height of the Florida Land Boom. The Beeman family then turned their attention to other ventures, such as selling off some Winter Park property—they called the new subdivision Beeman Park.

However, the next few years were rough for Lester. His nephew, Edwin (who was adored by basically all of Orlando), died unexpectedly at 34 years old from a botched appendectomy. Then, after a long illness, Harry died in March 1929. And his mother, Mary, died in 1933. Those same years saw the Great Florida Land Boom rollercoaster from boon to bust.

Despite the family traumas, Lester repurchased Palm Spring in 1930—probably at a significant discount. He reopened and updated the popular attraction. Soon after that, though, rival Sanlando Springs Tropical Park opened around the corner and began to outshine it.

By 1935, Lester sold the spring again—either that or creditors did it for him. Less than a year earlier, H. A. Stein purchased Lester’s 40-acre Winter Park mansion (built in 1910) for $21,000.

Ginger Ale Springs Today

Today, “Ginger Ale Spring” sits on a heavily wooded parcel that is half private property and half county-owned near Markham Woods Road. There, I found it, frozen in time, down a narrow windy path. There is no historical marker, no parking lot, and nothing to indicate its existence.

All that remains of the former bottling plant is a rounded cement tub that once collected the water for production. An opening in the cylinder creates a continuous waterfall from the overflowing sulfur spring. The green paint dating back to the 1920s is fading but still visible.

Nine smaller boils seep up from the sandy bottom below the waterfall, and another spout ingresses from a side wall. A colony of small fish populates the round pool of the main spring, with its white sandy bottom visible through a thin algae layer.

The county put up “No Trespassing ” signs shortly after this article was originally published in 2018 (oops, my bad!). Fortunately, the county accompanied me and a Channel 6 reporter for a November 14, 2023 visit. It was just as I left it five years ago!

It’s evident that a few locals know of its existence and ignore the signs. They leave trinkets and religious objects there. Some still believe in its spiritual healing powers, as people have for centuries. On our 2023 visit, we ran into a friendly homeless man (Harold), towel in hand, who said he had been enjoying the spring since 1989. He knew all about its history and firmly believed in its healing powers. He looked darn good for 60 years old, so he might be on to something!

It is a beautiful property, except for a few clumps of trash and beer cans closer to the river. Some people have no respect.

Mostly, Beeman’s Ginger Ale Spring sits undisturbed and unnoticed. It is oblivious to the nearby hustle and bustle, ignoring the civilization and subdivisions around it. It is still frozen in time, a token piece of old Florida within the Seminole County suburban sprawl. Let’s keep it that way, forever preserved.

Beeman Family Tree

This post is 2939 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.