Avon Park City Council Throws Out All Black Votes in 1951 Election

The good old boy system of Avon Park was shaken to its core in 1949. That September, five out of six incumbents were voted out of office. Among the newly-elected was young Wiley Sauls, who was just 21.

The story gathered widespread media attention that announced he was the youngest mayor in America. Sauls, a native of Avon Park, graduated from Avon Park High School in 1946 and then went to law school at the University of Florida.

The mayoral election of 1949 was hotly contested, with five candidates throwing their hats in the ring. In addition to Sauls, three other candidates (C. L. Armstrong, J. L. Elder, and Bert Turner) were running against incumbent mayor O. C. Wilkes.

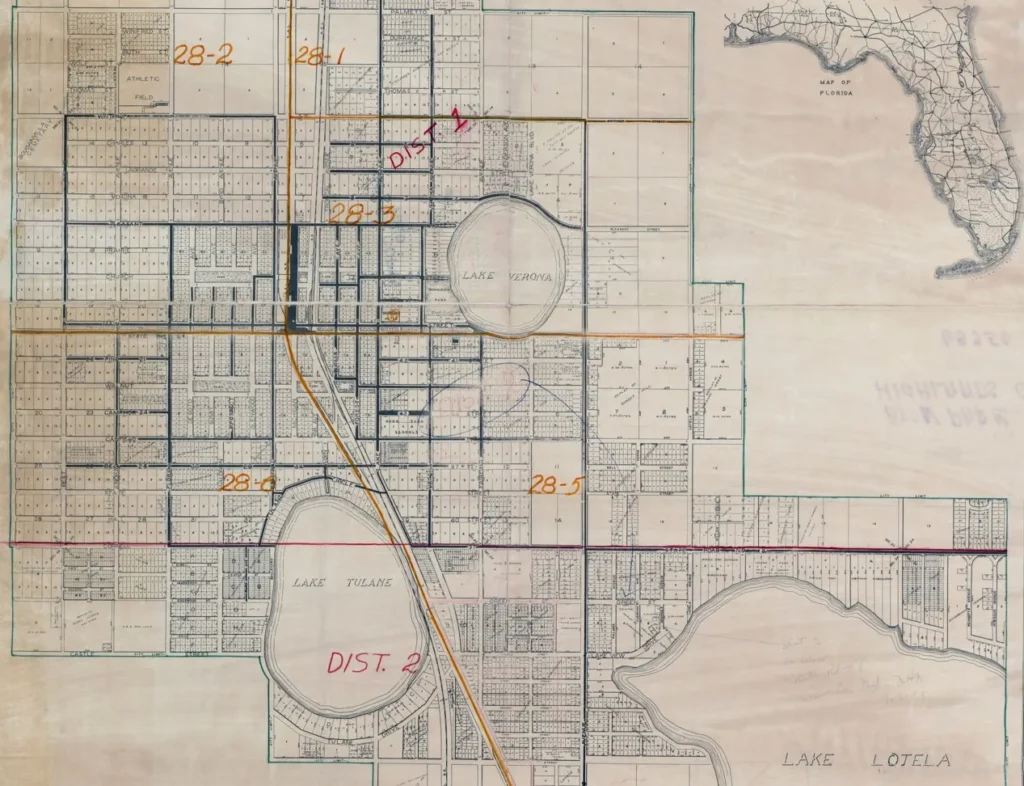

In setting the stage, remember mid-century Central Florida’s racial climate. Avon Park was rather typical of the Jim Crow South, segregated by law, including a strict color line for housing. The white population lived in the northern part of the city, and all voted in Precinct 1. A second precinct served the colored “quarters” of the city’s southern section.

Avon Park’s population was measured at 4,612 in the 1950 Census, with 72% being white. Blacks, long intimidated to stay away from the polls, were starting to have more significance in elections but still proportionally had a turnout of about 40% less than whites.

Although no candidate received a majority vote in the five-way race, the incumbent mayor dominated the others in the white precinct with 397 votes; his closest competitor (Armstrong) only had 242. The young legal scholar, Sauls, was tied for third with 237.

Just when it seemed like Wilkes would be re-elected, the black precinct’s tallies rolled in. The 21-year-old captured a whopping 76% of the black vote (225 of 295), and Wilkes only received 20 from the precinct. Sauls zoomed past Wilkes and into the mayor’s seat 462 to 444.

Fast forward to the 1951 election. O. C. Wilkes was determined to reclaim his mayorship over the youngster. A third candidate, O. K. McClure, would never be a real factor in the race.

That year was especially notable for the black electorate. For the first time, the black precinct was staffed and managed by its citizens. The overseeing inspector, W. J. Robinson, and the precinct’s clerks were all black. They finally had exclusive supervision of their own voting district.

When the white precinct reported its results, Wilkes had a narrow eight-vote lead over Sauls of 522 votes to 514. However, the black turnout came out in force and, once again, left no doubt about their preference. Of the 397 votes from the black precinct, an astounding 92.5% went to Sauls.

Wilkes was not amused. Nor was a significant portion of the white population. For the second election in a row, the black voters had overruled the desires of the white constituency. In addition to the mayor race, two new city councilmen (Mannin Kirkland and J. B. Sparks) were swept into office after trailing in the white precinct thanks to the black vote.

The City Council met on September 15th, four days after the election, and heard Wilkes’ protest. He insisted that there were voter irregularities in the black precinct and that the council should take action to correct the injustice and install him as mayor. After looking at the evidence, the council decided there was insufficient evidence and sustained the popular vote.

Undeterred, Wilkes started lobbying local influencers. He compelled the council to convene a special session on September 25th. Wilkes charged that Precinct 2 had not returned all of its unused (blank) ballots after the election, and therefore that called into question all votes cast there.

This time around (based on Wilke’s highly questionable logic), the council voted 3–1 (one abstained) to throw out the ballots of the entire black precinct. Immediately, O. C. Wilkes began acting as the town’s mayor, and councilmen Kirkland and Sparks were replaced by E. W. Gough and Oscar Wolff.

As you can imagine, the whole city was in disarray, and no one could figure out what was going on or who was in charge. The Wilkes administration began to make changes to the city staff, hiring loyalists and firing those in the Sauls camp. Two police offers were assigned to stand guard at the front of City Hall in a military-esque showing of the coup d’etat. Everyone was confused.

Barnett Bank made its position known; they wanted no part in the drama. They refused to honor the city’s checks until the courts sorted out the mess!

The political melee quickly gained statewide headlines and hit the Associated Press wire. It dragged on for almost three months. While the judicial system continued to side with Sauls and insisted the will of the people be upheld, Wilkes and company would not give up the fight.

Attorney Keith Collyer was hired by duly-elected mayor Wiley Sauls and the other two would-be councilmen, Kirkland and Sparks. Collyer contended this authority to the council would permit them to perpetuate themselves into office on a mere claim of irregularities.

Circuit Court Judge Don Register quickly agreed, stating that the council had no authority to change election results and ordered them to reinstate the rightful winners. He stated the city could not “usurp the judicial function by declaring all ballots cast in polling place number two to be void.”

When the shadow government refused to comply, Judge Register called them to appear on contempt of court charges in a Wauchula courtroom.

“Mr. Pardee (Avon Park city attorney) assured me that you gentlemen will meet tonight and carry out the instructions of the court.,” said Judge Register with a soft-spoken demeanor and a knowing smile, “This court has no desire to adjudge anyone with contempt of court — unless it is necessary.”

Council President Gough and the other councilmen facing charges hastily assured the judge that they would meet that night to reverse their action.

However, refusing to go easily, the appeals continued through October and into November. In addition to the charge that not all unused ballots were returned, Wilkes’ attorney S. C. Pardee, Sr., added that black inspector W. J. Robinson had assisted voters in filling out their ballots.

The election challenge made its way to the Florida Supreme Court, which made its final decision on November 20, 1951. The high court agreed with the ruling of Judge Register and brought a conclusion to the matter.

Kirkland and Sparks were installed as city council members. Wiley Sauls, at age 23, became the youngest re-elected mayor in the country. And municipal governments were put on notice that they did not have the authority to invalidate an election to remain in power.

There you have it! Avon Park was the battleground of an early civil rights victory. One great +1 for democracy, with many more to come in the next two decades!

P.S. — Whatever happened to Sauls? Less than two years into his second term, he resigned from the mayor position and moved out of state.

This post is 1281 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.