Muskmelons and Gun Powder: The Origins of Fort Maitland

Long before the luxury neighborhoods and modern apartments of Maitland took root, the western shore of Lake Maitland was a wild frontier and a strategic choke point along the military road between Sanford and Orlando. To understand its history, we have to look back 180 years to a time when Central Florida was a landscape of broken promises, where a one-armed colonel directed soldiers to carve a path through the palmettos.

The People of the Muskmelon Place

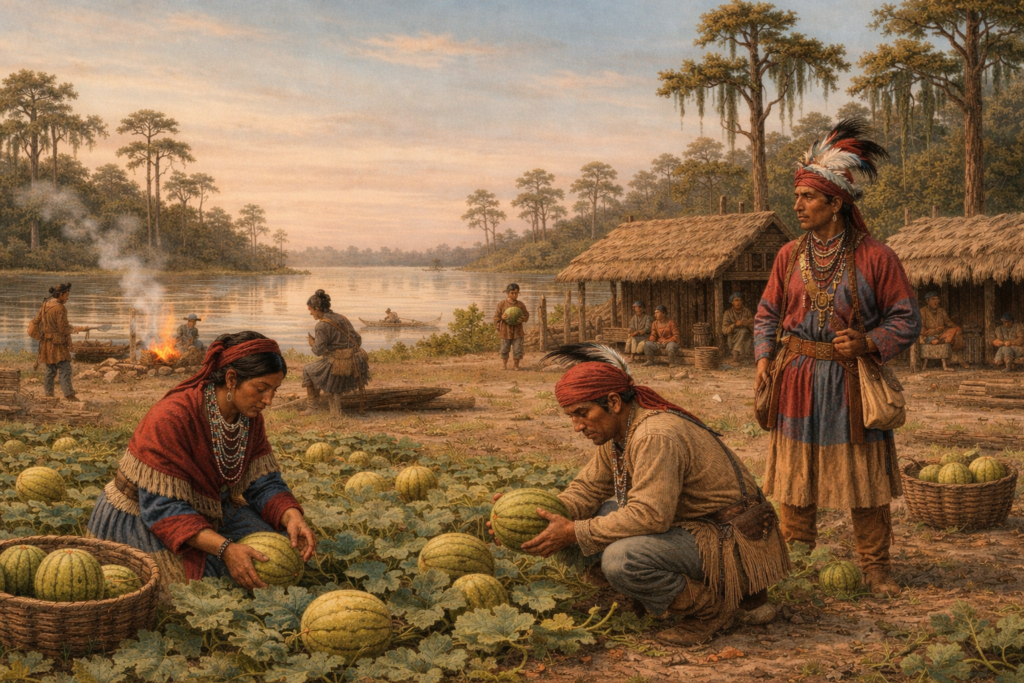

Prior to Spanish arrival, this region was the domain of the Mayaca people. Unlike the agricultural tribes to the north, they lived off the river’s bounty—freshwater snails, fish, and turtles—leaving behind massive shell mounds as a record of their millennia here. By the mid-18th century, however, these original Floridians had vanished, victims of Spanish diseases, warfare, and forced servitude.

Into this void moved the Seminoles, a multi-ethnic coalition of refugees and Creek Indians seeking independence from colonial encroachment. They knew this area as Fumecheliga, or “Muskmelon Place.” It was said the air smelled sweet from this crop grown here. The muskmelon itself was native to Persia, introduced to the United States by colonizers, and cultivated by Native Americans.

The beautiful sheet of water that we now call “Lake Maitland” was known as Lake Fumecheliga until 1838. To the Seminoles, these lakes and rivers were not just scenery; they were a sanctuary, part of a liquid highway that allowed them to vanish into the sawgrass at a moment’s notice.

A Legacy of Betrayal: The Commercial Chokehold

The peace of “Muskmelon Place” was shattered by the Second Seminole War (1835–1842), a conflict fueled by broken promises and the systematic theft of native land. It began with the Treaty of Moultrie Creek (1823). While framed as a compromise, it was a geographic exile. The Seminoles were forced to relinquish 24 million acres of fertile North Florida for a four-million-acre reservation in the center of the peninsula. This tract encompassed much of modern-day Orange, Seminole, and Osceola counties and beyond.

The U.S. government drew these boundaries to keep the Seminoles at least 15 miles from any coastline. By confining the natives to the interior, the government could cut them off from trade, preventing them from acquiring arms and wealth from foreign powers such as the British or Spanish. Landlocked in the swampy interior, they were stripped of their independence and of their fertile agricultural land in North Florida.

The betrayal deepened with the Treaty of Payne’s Landing (1832). Many native leaders claimed they were tricked or forced into signing removal agreements. The government demanded the total removal of native tribes to Oklahoma. Many complied, but some fought back. This culminated with the capture and ultimate death of revered Seminole leader Osceola, captured under the false flag of a truce in 1837.

The One-Armed Colonel and the “Skeleton of Defense”

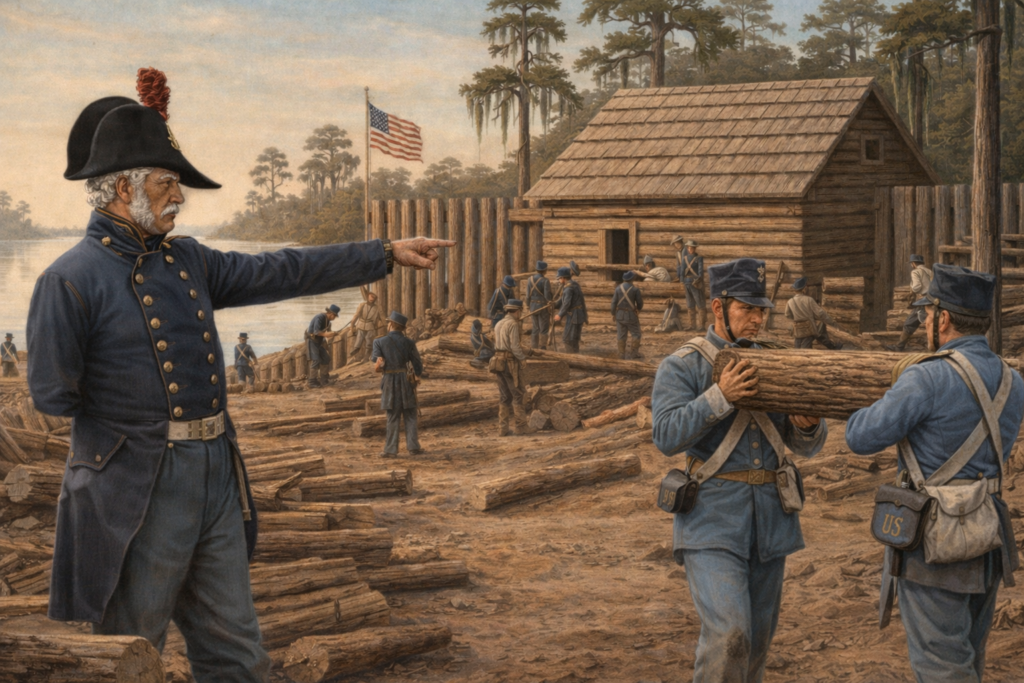

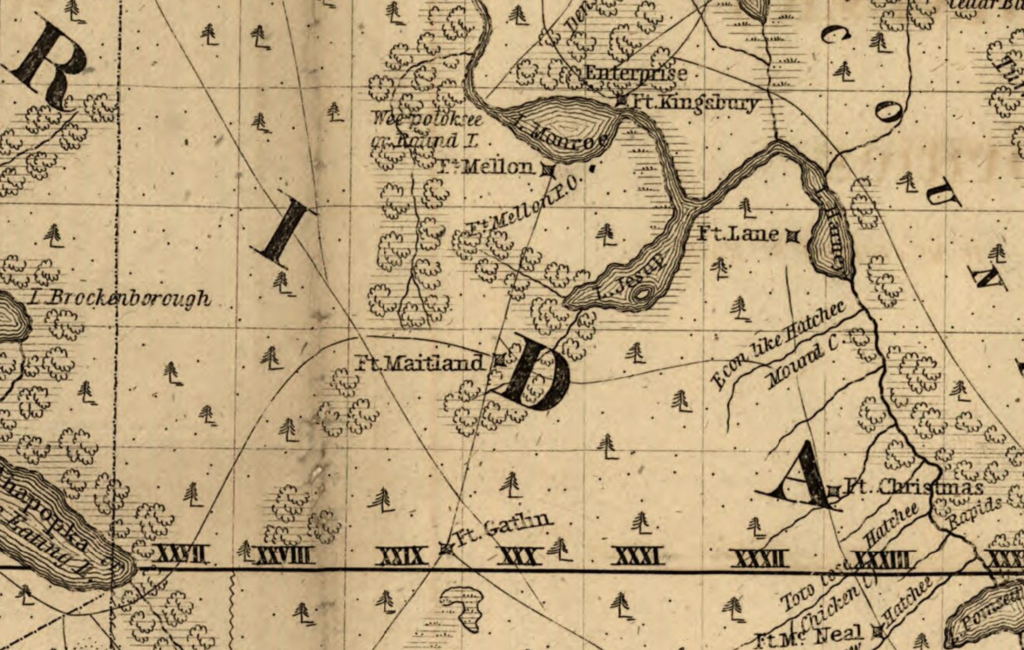

By 1838, General Zachary Taylor (the future U.S. President) took command with a systematic strategy to penetrate the “trackless waste” of Central Florida. He envisioned a “skeleton” of defense: a chain of forts and military roads spaced about 20 miles apart—exactly one day’s march for a soldier. These forts provided a safe line for troops and supplies as they scoured the maze of swamps.

The task of building the Maitland link fell to Lt. Col. Alexander C. W. Fanning. Fanning was a grizzled veteran who had served in Florida for over twenty years. Most remarkably, he had lost an arm during the War of 1812, yet he remained a dominant force on the battlefield. Picture him in November 1838, a one-armed officer standing amidst the humidity and sawgrass, directing Company K of the 4th U.S. Artillery as they hacked a narrow military trail through the wilderness.

This road was the lifeline of the campaign, connecting Fort Mellon (modern-day Sanford) to Fort Gatlin (south of Orlando). Fort Maitland was constructed exactly 14 miles south of Fort Mellon to serve as a vital rest stop and supply depot on this trail. They chose a “superb and commanding position” on the western shore of the lake, in a cove with an excellent view to the east.

The fort was a typical frontier fortification: a pine picketing stockade fence roughly 110 feet square. It featured blockhouses at diagonal corners, which were essentially two-story log cabins. The second floor was used for lookout and defense, lined with small holes called “loopholes” just large enough for a rifle.

It was never the long-term home base for soldiers and never saw battle; it was a primitive, mosquito-infested stopover for the 4th United States Artillery. It allowed a garrison of 75 to 80 men to hold off an attack while guarding the road. But its lifespan of military usefulness was just four years. By 1842, the government was tired of the expensive war effort, and the fort was left to rot in the Florida humidity. Its outline was still clearly visible when Maitland was incorporated in 1875.

The Namesake

The fort was named to honor Captain William Seton Maitland, a West Point graduate who had shown immense gallantry at the battles of Withlacoochee and Welika Pond. In a twist of historical irony, Maitland never actually set foot on the ground that bears his name. He was only named the fort’s namesake because he had died a “hero” of the conflict fourteen months before construction began.

His story is one of the war’s most poignant tragedies. Severely wounded at the Battle of Wahoo Swamp in 1836, Maitland spent months in physical agony and mental distress. In August 1837, while traveling by steamboat to South Carolina, he suffered what newspapers of the time called a “temporary fit of derangement.” Despondent over his injuries and the necessity of leaving his men in the field, he leaped from the ship and drowned. The naming of the fort was a posthumous tribute, a memorial to a man who literally lost his mind in the war he fought.

Hanna’s Rediscovery

For nearly a century, the fort’s location was lost to encroaching scrub and the expanding citrus industry. The old fort site had been absorbed into a private estate, constructed by architect and carpenter William S. Waterhouse. He built a home here in about 1885 for Charles H. Hall of Marquette, Michigan, who had bought the land in 1874.

Its history might have been buried forever if not for Professor Alfred Jackson Hanna of Rollins College. In 1934, Hanna conducted exhaustive research in the War Department archives in Washington, D.C., finally securing the maps needed to pin down the fort’s exact location. There, he unearthed the original military records and maps that pinpointed exactly where Fanning had driven his pine posts into the earth.

Because the site was already developed, formal archaeology was never feasible. However, Hanna wrote an important book about his research, the early development of Maitland, and the work of the Fort Maitland Committee. Edward R. Hall (son of Charles), who still lived in the home to the south, donated the parcel for use as a public park. The Hall home was located to the south of the park, where West Cove Condominiums is today.

The Fort Maitland Committee, with funding from the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, marked the spot with a coquina rock base (located in Titusville by Hall), a bronze plaque, and a historic marker. Several hundred people attended the dedication ceremony on March 14, 1935. The dignitaries included families of Maitland pioneers, Professor Hanna, General Avery D. Andrews (presenting the US Army), Mrs. Roy V. Ott (a descendant of Zachary Taylor), and W. Stanley Hanson (secretary of the Seminole Indian association).

In a powerful piece of historical drama, during the ceremony, the marker was unveiled by Chief Charlie Cypress (wearing the full ceremonial dress of a chief). He and fifty other Seminoles traveled from their home in the Everglades and camped at the location the day before the ceremony. They were treated as guests of honor in town–the descendants of the very people the fort was designed to remove.

Fort Maitland today

Today, the legacy of that rugged outpost lives on at Fort Maitland Park on the east side of Orlando Avenue (US 17-92). The three-acre park features little more than a parking lot, picnic tables, restrooms, and a boat launch.

The conquina monument and historical marker were moved in 1980, during a US Highway 17-92 widening project. Newspaper reports say they were relocated to the shores of Lake Lily. The rock is now in the median of the entrance to West Cove Apartments. Google Street View from 2022 shows the highway marker near the park’s entrance. However, it appears to have been removed by 2023, and I was unable to locate it on my visit on December 29, 2025.

While the sounds of traffic have replaced the rhythmic thud of a soldier’s boots and the quiet rustle of the Seminoles’ muskmelon gardens, the park remains a silent witness to the history of the town that was built around its fort and the geographical significance to native Americans before it.

Primary Sources

- Book: “Fort Maitland: Its Origin and History” by Alfred Jackson Hanna (1936) https://www.worldcat.org/title/fort-maitland-its-origin-and-history/oclc/1917711

- Maitland Historical Trail by Steve Rajtar (2008)

- Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine (June 1936)

- Monument Moved – Orlando Sentinel (November 7, 1980)

- Dedication Ceremony Report – Fort Myers News-Press (March 14, 1935)

- Florida Seminole Wars Heritage Trail Guide by John and Mary Lou Missall (2015)

- Mayaca-Jororo, the native people of Orlando

- UCF RICHES: Fort Maitland historic marker