East Altamonte Clings to its Heritage

Against all odds, East Altamonte has persisted for over 130 years. The historically black community is surrounded by valuable real estate and three land-hungry municipalities.

“In 20 years, Winwood will not exist,” Alcee Hastings, the community’s most famous son, said in 1981. “At the turn of the century, what we know as Winwood will be a massive shopping center or something… There’s no question about it. It’s just a matter of time.”

Hastings (before he died in 2021) was Florida’s first black federal judge and served for 28 years in the US House of Representatives. He was born in the “colored section” of Altamonte Springs in 1936 to parents Mildred L. Merritt and Julius “J. C.” Hastings. After graduating from Crooms High School, he earned a law degree from FAMU in 1963.

Today, we are 20 years beyond Hastings’s doomsday prediction for his hometown. It’s safe to say Hastings was wrong. Winwood—or East Altamonte—lives on as a distinct black community, an island among its mostly white suburban neighbors. Its long and tumultuous history is still being written.

Winwood or East Altamonte?

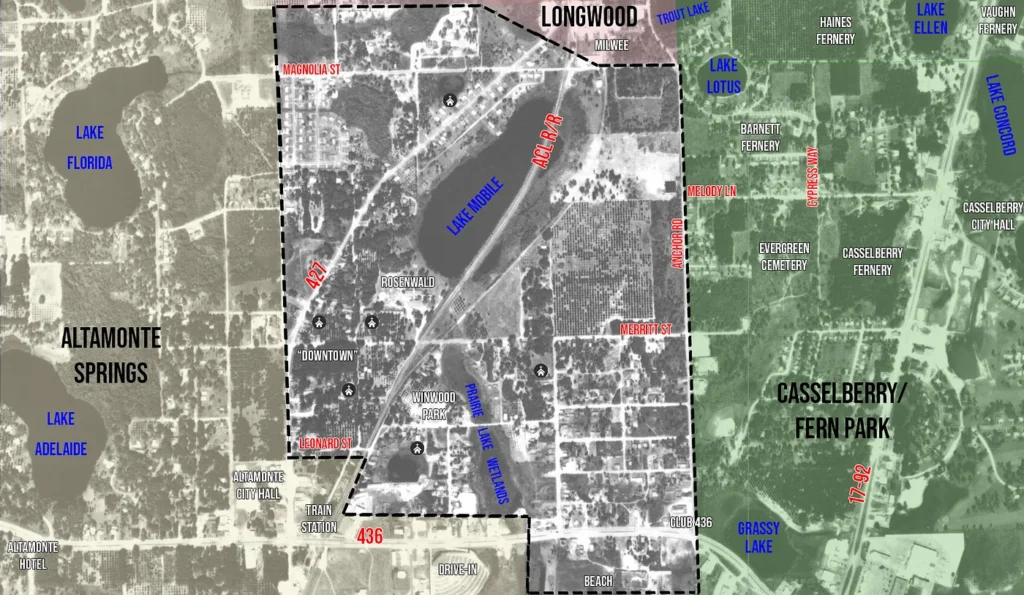

East Altamonte is roughly considered between Sanford Avenue/427 on the west, Campello Street on the north, Anchor Road on the east, and State Road 436 on the south. It sits mainly within unincorporated Seminole County.

The area is often referred to as “Winwood,” named for the subdivision of Winwood Park within East Altamonte. However, there are 14 other neighborhoods within the community: Frost Addition, Lakeview, Hayman, Granada South, Griffin Park, Merritt Park, Lula Blake, Grove Terrace, Harmony Homes, Lake Mobile Shores, Magnolia Hill, Orange Estates, Sanlando, Oak Park.

Another name sometimes heard is “Black Bottom.” This is the northwest section of East Altamonte near Sanford Avenue. It used to be dark and heavily wooded, with a deep trench that divided it from Hermit’s Trail. It was called “black” for its lack of light, not its population.

Winwood is the largest and most prominent subdivision in East Altamonte. It was home to the black downtown district, Rosenwald School, and several churches. A marker went up in 2017 for “Historical Winwood.” Newspaper references have commonly used this name over the years, and even Alcee Hastings favored it.

However, many families who have lived there for generations will quickly correct you! This seemingly minor point can be contentious by those who feel it excludes their neighborhood. I’ll use “East Altamonte” in this article.

Early Settlement of Altamonte Springs

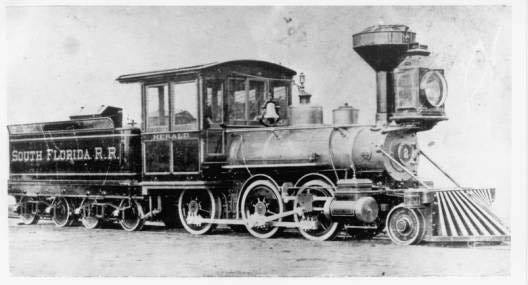

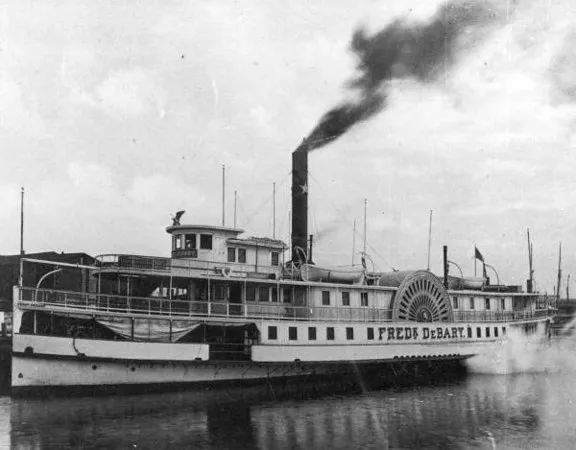

Although a few people trickled in earlier, the real start was in 1880 when the South Florida Railroad opened. Regular service from Sanford to Orlando began in November with a flag stop called Snows Station at the halfway point; it was renamed Altamonte Springs around 1883. This was the only rail line south of Jacksonville. Travelers arrived in Sanford via steamship down the St. Johns River before getting on the train.

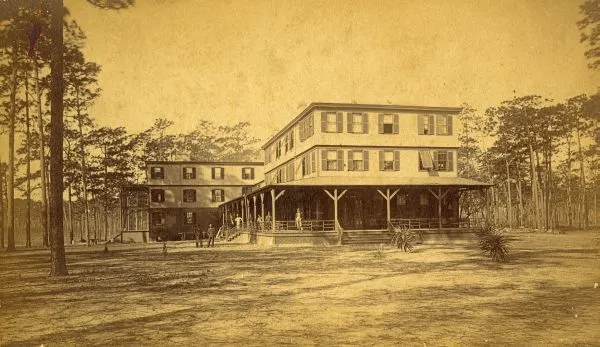

Wealthy New Englanders (mostly from Boston) came to the area as tourists and investors. The Altamonte Land, Hotel & Navigation Company opened the swanky Altamonte Hotel at the southwest corner of 436 and Maitland Avenue in 1883. That’s when momentum picked up.

Many of the hotel’s guests decided to take up a second residence in Altamonte Springs. They built three-story “cottages” on lots surrounding the hotel and lakes Orienta and Adelaide. The wealthy clientele included the Bradlee and Westinghouse families, who would spend up to six months a year in Altamonte Springs. Doctors regularly prescribed wintering in Florida to promote good health.

In the first couple of decades, there were few permanent residents in Altamonte Springs. The population dwindled from around 250 to a few dozen during summer. However, there was year-round work to serve guests and maintain the grounds.

Further, many part-time residents invested in agricultural endeavors in Florida. Citrus groves were beginning to become profitable. Some tried pineapples, tomatoes, celery, cucumbers, and other crops.

Black laborers were essential at every step of the way. They laid the railroad tracks, built the homes, prepared meals, did the laundry, and worked the farms. During those summer months, most of the town of Altamonte Springs was black. They were the engines that kept the wheels turning in the pioneer town.

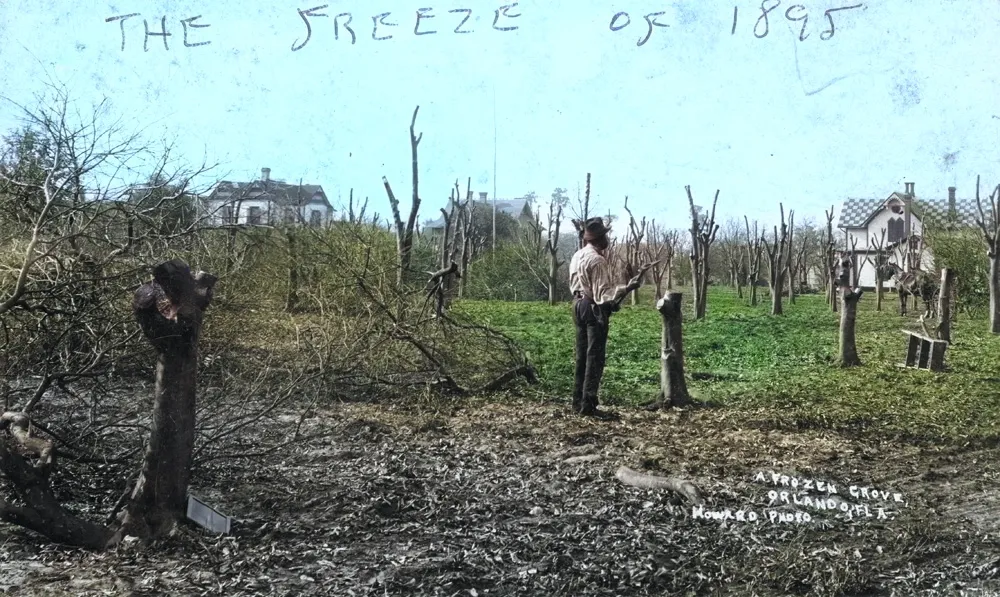

The Great Freeze

Things were going smoothly for Central Florida, with tiny settlements dotting the countryside. By 1890, every little corner had its own post office, church, and schoolhouse. Numerous railroad lines cut new trails to the previously impenetrable wilderness. It seemed there were boundless opportunities in the Florida frontier.

For many, those dreams vanished in 1895. Two successive freezes killed decade-old groves to the roots. The fallout was quick and pronounced. Many people lost everything, packed up, and went back north, never to return. Towns vanished overnight. Most railroad lines went bankrupt, and dozens of small villages consolidated into a few.

Altamonte Springs was a benefactor of the town mergers. Settlers from Lake Brantley, Altamont (no “e”), Palm Springs, Concord, Spring Lake, Forest City, Mayo, and others gravitated toward the remaining railroad and the shores around Lake Orienta.

Many orange groves were replanted; however, citrus does not bear fruit for seven years. So it took multiple decades for the Great Freeze’s scars to heal. In the meantime, agriculturalists looked for other types of crops that could yield more quickly.

They planted cotton and sugar cane, but neither did exceptionally well. There was some success with pineapples, which took around 18 months to harvest. The fruit thrived in the shade, so farmers grew the crop under the cover of slat housing.

As a bonus, the shade houses lent some protection against frost. On especially chilly nights, workers lit fires as an additional defense. Black laborers were in charge of keeping the oil fires lit all night long.

These same techniques would prove invaluable skills for the coming crop that transformed the landscape in southern Seminole County.

King Fern Takes Over

The Pierson family of Volusia County was the first in Central Florida to grow ferns, starting in 1904. They borrowed the technique from pineries by building shade houses, which also allowed workers to tie the ferns to encourage height. The higher elevation and sandy soil were perfect for growing the prized indoor ornamentals.

Wealthy New York congressman Charles Delemere Haines moved to Altamonte Springs in 1911. His estate spanned nearly the entire western side of Lake Orienta. As a side project to his expansive orange groves, Haines started with just six acres of ferns. The experiment was a huge success and profitable by 1913.

Haines founded the Royal Fernery that year and devoted increasingly more acreage to asparagus ferns. By 1920, everyone in the area was getting into the business, from small backyard farms to huge enterprises spanning dozens or even hundreds of acres — all under shade houses.

Big fern bosses included the Haines, Kingsley, Webber, Barnett, Ballard, Casselberry, Hattaway, and Vaughn families. Fern horticulture overtook citrus as the largest industry in Altamonte and birthed the nearby town of Fern Park in 1925.

Company Towns

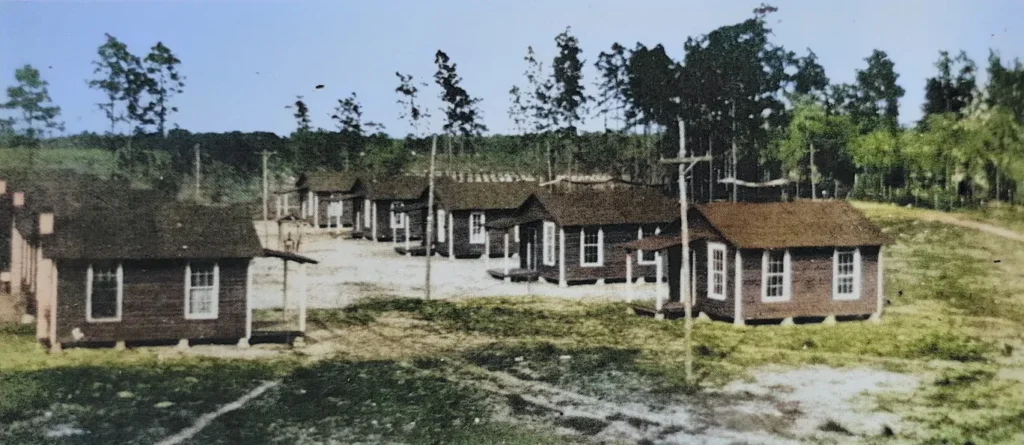

Large agricultural enterprises created company towns. Black laborers and their families lived on-site at the grove, farm, sawmill, turpentine still, or nursery in tiny “shotgun houses.” The shacks were no more than 12 feet wide and usually no more than 15 or 20 feet long, with only one or two rooms and a small porch.

These villages were all over the county. Each was self-sufficient, with a company store, church, and sometimes a one-room schoolhouse. This free housing was essentially the successor to antebellum life on a plantation. The communities were referred to by names like the Barnett Quarters, a clear throwback to slavery.

Altamonte’s eastern side of the tracks was its largest concentration of laborer camps. Wooden shanties of the earliest black settlers appeared as early as the railroad’s construction in 1880.

South of Prairie Lake, the sister settlement of Woodbridge began around the same time. Spring Lake (near Forrest City) sprang to life on the west side of town soon after. To the east was Wagner, near Winter Springs, where the Chase Company had a farm growing vegetables.

Another concentration of black settlers lived southwest of Longwood, near Island Lake and Rangeline Road. They first came as workers for the Florida Midland Railroad in 1885. They built shanties just off the embankment for the tracks, which paralleled Warren Avenue and 434. Later, many worked at turpentine camps and sawmills. Some became farmers with vast acreage of their own, such as the Jones and Shepard families.

Each of these black communities was interconnected. They depended upon each other and partnered in social, religious, educational, and commercial endeavors. In many cases, they were kinfolk, with cousins spread around the county’s southern end.

Among those five or more settlements, East Altamonte began to build the most momentum as a cultural center for African Americans living in southwest Seminole County. There was a large concentration of ferneries on all sides across Altamonte, Casselberry, and Fern Park, providing constant opportunities for work.

Laura Payne Brawner donated 16 acres for use as a cemetery by the folks of East Altamonte in 1890. The Brawner family owned a plantation in Virginia and relocated (with some of their former slaves) to Maitland around 1878. The property, behind the Target complex in Casselberry, later contained rows of shotgun houses for fernery workers.

It was dedicated as Evergreen Cemetery in 1903, and in recent years, Alton Williams and his volunteer team have restored it from ruin to gem. A museum is being constructed on those grounds.

First Churches in East Altamonte

Religious life was paramount in the black community, dating back to plantation times. Churches are central spiritually, culturally, and socially. They also commonly served as the first schools. So, it’s no surprise that churches were the first institutions to appear in frontier Seminole County.

On Sundays, many East Altamonte faithful attended Corinth Baptist Church in Longwood, which opened in 1883. As time went on, however, folks grew weary of the ten-mile roundtrip walk down the sandy trail. The growing population needed its own house of worship.

One of those devoted members was Amanda Samuel. She was born in 1859 and moved to the eastern section of Altamonte in the 1890s. In 1938, at the age of eighty, she told how her church was founded.

Founding members met in 1902 to organize Bethel AME Church, gathering under a brush arbor near the current location. These early structures were crude but effective. They would have been a few hewn logs as walls with branches on the roof and shrubs (or palmettos in Florida) for shade.

Pastor J. H. B. Jackson led members to raise funds for a more sturdy building. Grilling barbeque for three days, congregants earned the $80 necessary for materials. The entire community pitched in to construct a plain, unpainted, boxy edifice that became their first sanctuary.

They worshipped in the original structure for the next 30 years. It was replaced with a larger building in 1933, salvaging the best material from the old church. Over the years, the congregation continued to expand, and the current building was constructed in 1966.

St. Peter Freewill Baptist was founded in 1905 at a turpentine company town southwest of Longwood. Reverend D. H. King was its first pastor. In 1908, the wood building was disassembled and moved to its present location on 427 in East Altamonte. That building was destroyed by fire in 1913, and worship was held in a palmetto arbor for five years. A larger building with a bell was constructed in 1918.

Its current beautiful edifice was constructed in 1975.

St. John Missionary Baptist, located prominently on 427 and Hayman Street, was formed in 1914. Services were first held in the schoolhouse. Under their first pastor, J. H. Robinson, members built a small shed-like structure that served until 1929, when it was destroyed in a hurricane.

A white, rectangular building with a small tower and bell was erected in 1930. The current block sanctuary was constructed in 1949.

Williams Chapel Baptist has its roots in Royal Fernery’s company town. It began as Royal Fern Union Church under Reverend J. W. Knox in 1923. The unpainted wood building with a bell was in the Haines Quarters west of Lake Orienta. It was renamed Kingly Chapel in 1925.

Many of its members moved to East Altamonte, and in 1929, they formed Alpha Monumental Church. Its first pastor was John W. Ford. Services were held in a small, unpainted wooden schoolhouse near the railroad tracks.

In 1935, the Reverend Booker T. Williams started his ministry at Kingly. Two years later, he took on double duty as pastor at Alpha. As company towns became a thing of the past, the population at Royal Fernery dwindled.

When Rosenwald School opened in 1933, the county school board donated the old schoolhouse to the church. It was dismantled in 1939 and rebuilt at its current location at Marker and Williams Street. The two congregations merged on January 25, 1939, and the church was renamed Williams Chapel after its minister.

Incorporation of Altamonte Springs

Altamonte Springs leaders summoned citizens to discuss incorporation on November 11, 1920. With 45 in attendance, the delegation voted 38 to 7 to form the city — 30% of these founding voters were black.

This introduced new formality to the pioneer town: elections, taxes, improved streets, and zoning laws. The timing coincided perfectly with the Great Florida Land Boom, which welcomed hordes of investment dollars and new northern settlers.

Everyone knew that the city’s black population was fundamental to the town’s success; however, full membership in society was not on the table. While the South was fifty years beyond slavery, the relationship between blacks and whites in many ways remained the same.

Black residents, whites felt, should always be on hand to play a supportive role — never a leading one. Blacks could participate in society only to the extent that they were invited. Many places were considered off-limits, and deference toward whites was a requirement.

When real estate developers marketed to northern investors, there was a sweet spot in the message they wanted to convey:

1) There were plentiful blacks available for cheap domestic and field labor.

2) They lived within a separate colony.

3) They didn’t intermingle outside of the professional realm.

Rebirth of the KKK

As women won the right to vote in 1920 and the black middle class grew, white leaders began to feel their power slipping away. Further complicating things, an influx of northern settlers weakened the Democrats’ vice grip on southern politics.

The Yankee Republicans worked with black leaders on voter registration drives. Democrats opined their efforts were not out of legitimate concern but merely to manipulate them into voting Republican.

This power of an enfranchised “colored” class was immense. Blacks and mulattos made up nearly 50% of the population in Altamonte Springs. Rather than embracing would-be black voters, white institutions took the opposite approach: suppression by any means necessary.

As a result, the KKK awoke from its dormancy. Klan membership filled Central Florida’s government and religious ranks during the 1920s. It’s hard to overstate its influence. Even those who did not support the Klan put their lives and livelihoods at grave risk to publicly dissent.

Nearby Ocoee had its black community wiped off the map overnight in 1920 when a get-out-the-vote campaign started to gain steam. For the next twenty years after that event — I’m not exaggerating here — there were virtually zero black voters in Orange, Lake, or Seminole counties.

Until then, blacks and whites in Altamonte lived separately out of unspoken social norms and practicality. However, the resurgent Klan began to insist upon constraining the black population. Company towns were phased out, and black laborers were required to move mostly east of the railroad tracks.

This almost came to bloodshed in 1932. An unidentified fernery owner defied the mandate by asking his black foreman to live at the nursery. The boss insisted the foreman’s full-time presence was imperative to the fernery’s operation.

The Ku Klux Klan did not agree. The hooded gang gave the foreman one day to remove himself… or else. He wasted little time packing. The fernery owner was livid and appealed to the police chief, Melvin Tyler; the chief refused to intervene. The owner started a petition to fire the chief, but few agreed to sign it.

As the population continued to grow — both black and white—demand for housing increased. The line between the white and black communities began to get fuzzy, and more conflicts were not far behind.

Pleasure Island Beach

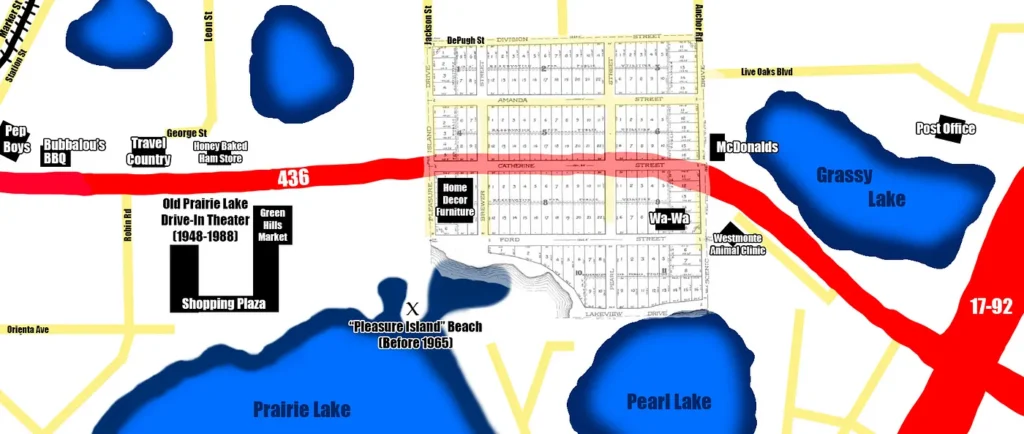

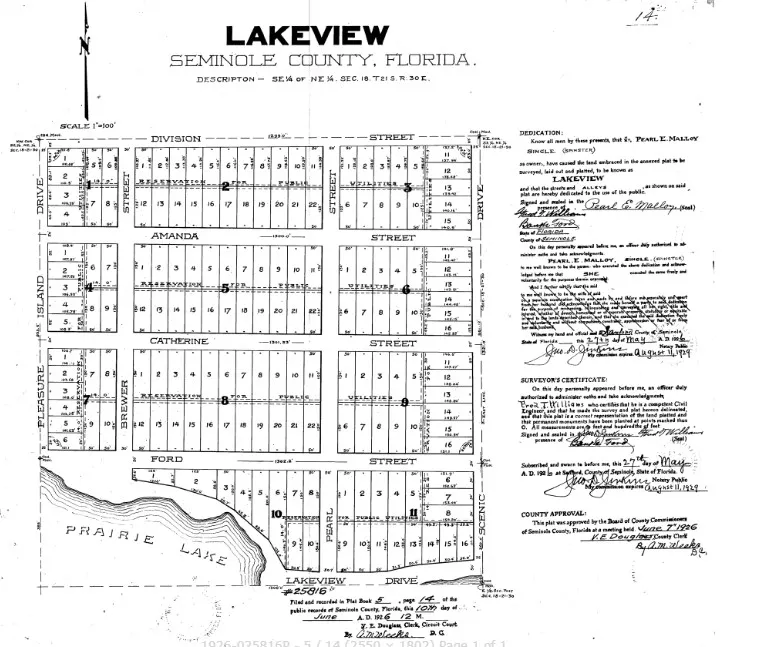

Near the intersection of modern State Road 436 and US 17–92 is Pearl Lake, named for black seamstress Pearl Malloy. The unmarried 30-year-old saved enough money from her dress-making business to purchase 11 blocks east of Altamonte.

The plat, which she called Lakeview, spanned both sides of what is now 436 (which did not yet extend past the train station). It was bounded by Jackson Street on the west, Anchor Road on the east, DePugh Street on the north, and Prairie Lake on the south.

Several East Altamonte families, including the Ford clan, settled in Malloy’s subdivision. The homes were along the northeast shore of Prairie Lake, between WaWa and the former drive-in movie theater (1948–1988), which is now a large shopping plaza.

On the original plat, modern Jackson Street is called Pleasure Island Drive. Beyond its southern terminus at 436, a dirt path continued south.

Today, hidden behind what is now a furniture store, there is a large estate called Via De Lago. Ahmed EL-Hawary, a restaurateur, real estate mogul, and former UCF offensive lineman, owns the mansion. In the days of segregation, this enclave was one of the only beaches for black residents. They called it Pleasure Island.

Black visitors from all around flocked to its beautiful sandy shores. It’s easy to see why it was called an “island.” Prairie Lake’s large former footprint spilled all around it, and only a narrow causeway connected the beach to the mainland.

Many people still alive recall it as the paradise of their youth. It was close enough to the drive-in theater, which opened in 1948 that they could watch (but not hear) movies from the sand. In those early years, they could not enter Prairie Lake Drive-In.

Blurred Lines

Being so far removed from white homes, neither the beach nor the subdivision east of town bothered anybody. Besides, it was well outside the city limits at the time.

However, in 1945, a black insurance salesman named Willie Grant began constructing a house further west on Prairie Lake. This was still east of the tracks but too close for comfort. The powers that be decided to end this expansion of black territory.

After fiery debates, the city council patted themselves on the back with a compromise! They’d allow Grant to finish his house — and live in it — but added a deed stipulation that he may only sell it to a white person. Further, they defined the new “color line” as north and east of the intersection of Leonard Street and 427.

Self Reliance

Corralling the black population as if they were cattle is immoral. Full stop. However, it had a positive side effect: East Altamonte’s identity as a culturally unique black community was cemented. Black entrepreneurship thrived, churches developed, a vibrant social life emerged, and youth were raised to be proud of their heritage.

The environment nurtured a combination of an independent spirit but also interdependence with others in the community. Even as the population expanded, it largely grew from just eight or ten families whose family trees branched and intertwined over the generations.

Family clans would often settle in clumps of houses within a single block. There was inevitably a garden patch growing much of the food they needed: peppers, peas, greens, peaches, pecans, kumquat, watermelons, and beans. Oranges were always plentiful, with groves in every direction.

Most also raised chickens or pigs. Fishing was universal: a bounty could be caught in a half dozen nearby lakes. What little they could not provide for themselves could be picked up at the black-owned groceries “up the street” or a trip to the Margaret Ann supermarket in Sanford every few weeks.

Colored Schools and the Rise of Rosenwald School

The legislature in Tallahassee passed a new state constitution in 1885. It required counties to levy taxes to make a free “common school” available to all students, regardless of race. However, it also insisted upon segregation: “white and colored children shall not be taught in the same school, but impartial provision shall be made for both.” Separate but equal.

The area’s first school for black children was opened near Spring Lake (between Forest City and Altamonte) in 1886. Two years later, a teacher was hired for a school in East Altamonte. These schools served 1st through 8th grades, with any students seeking higher education traveling to Sanford.

The county paid the teachers’ salaries, with black teachers making half that of whites. In the early years, there was no dedicated school building for the black community in southern Seminole County. Classes were held wherever they could find space: homes, churches, or the Masonic Lodge. Later, one-room, unpainted, wooden schoolhouses were built.

In 1927, the county acquired eight acres from black sawmill laborer Henry Wilson on the south shore of Lake Mobile to construct a school. Funds of $4,000 were raised for its construction in 1931; Sears co-founder Julius Rosenwald’s philanthropic foundation matched it dollar-for-dollar.

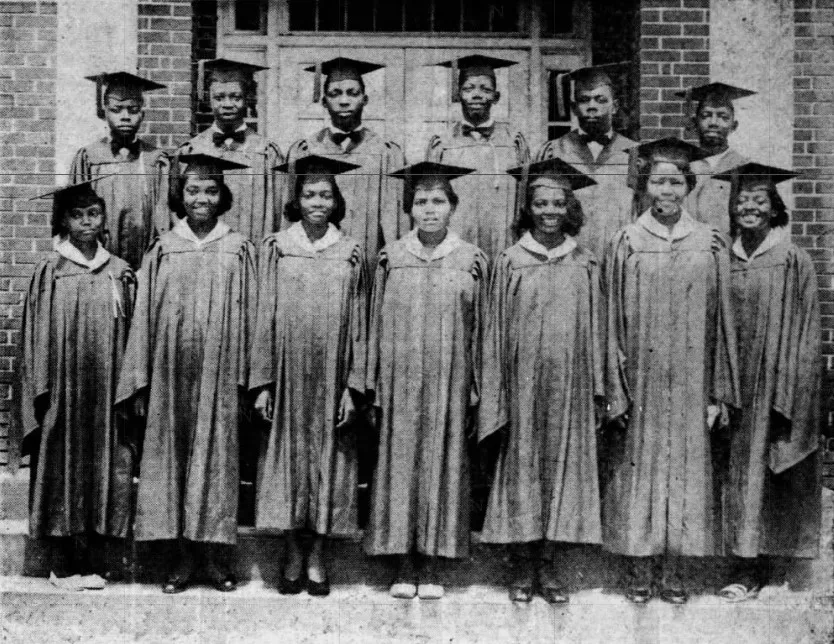

Rosenwald School opened in October 1932. It was a one-story brick structure with four rooms. It consolidated the four inadequate wooden schoolhouses in East Altamonte, Longwood, Woodbridge, and Forest City. Rosenwald served 135 pupils and four teachers, in its first year.

Rosenwald became more than just a school; it was central to the cultural identity of East Altamonte. Plays, concerts, beauty pageants, graduations, and other ceremonies brought out most of the population.

Outside of school activities, it hosted meetings for other organizations like scouting, clubs, and community activist groups. Immunization drives and health fairs were held there. There were dances and fundraisers. It was a source of pride and a symbol of the close-knit community.

Additions to the school were approved in 1959, expanding the campus into multiple wings. One of the new buildings was the cafetorium, a cafeteria that doubled as an auditorium.

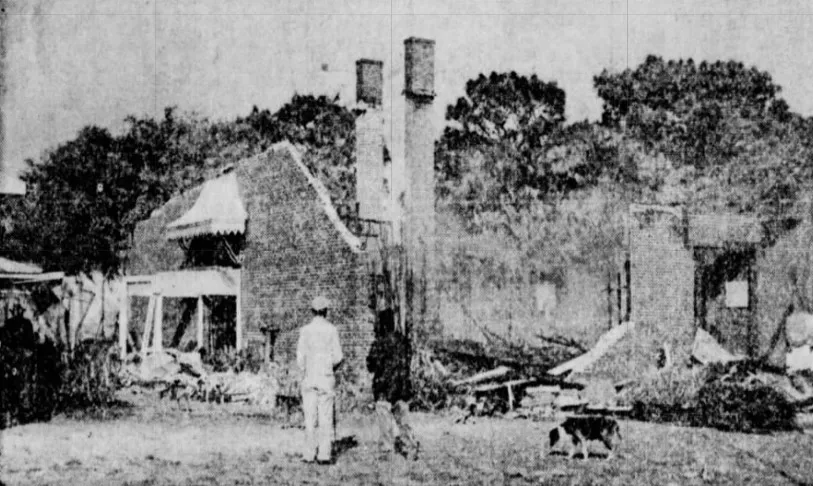

Sadly, the original building was destroyed by a suspicious fire after midnight on February 18, 1960. The brick structure was destroyed, but firefighters heroically saved the concrete additions. A year later, the city replaced its outdated and leaky fire equipment, largely due to its poor performance at Rosenwald.

Volunteer fireman and Altamonte Springs councilman John Wolf was badly injured in the blaze when a brick wall collapsed on top of him. He spent four months in Florida Hospital, recovering from burns and broken bones. Over the next two years, he underwent five surgeries, including amputating some of his toes. Both white and black sections of Altamonte came together to raise money for his medical expenses.

Despite the blaze, the school reopened the next week. Forty percent of the school’s 350 students had attended classes in the destroyed building. Local churches stepped forward to provide temporary classroom space for the remaining semester. Further expansion was already under construction before the fire and completed before the fall term.

Black Downtown and Entrepreneurship

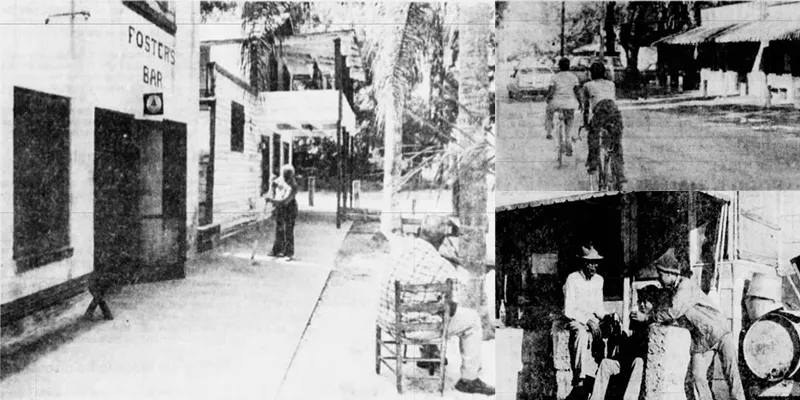

The palm-tree-lined business district, which residents called Up-the-Street, was centered on the intersection of Longwood Avenue (427) and North Street (now Merritt Street). It filled the block east to Market Street (now Marker) and extended north and south along Longwood Avenue.

It is amazing that these scrappy laborers — often making half that of working-class whites — scrimped nickels at a time from housework or farm labor and transformed them into property ownership and business ventures.

John and Laura Ford were among the first to do so, and they opened a general store in 1910. Their son Banks Ford carried on the tradition decades later, owning a two-story commercial building on 427. On the first floor was his drug store and confectionary, and a beauty salon run by Wiley and Rachael Coker occupied the second floor.

Ford stocked modern drugs alongside old-fashioned remedies passed down from antebellum times or earlier. Doctors from other Central Florida black communities would visit Banks’ Drug Store to pick them up.

Next to the drug store was Irving Bolden’s grocery store. One building over Morris Foster owned the popular Foster’s Bar. In front of the bar, a shoe shine stand was kept busy.

The district had at least two restaurants: one owned by Red and Emily Bush and the soul food restaurant of Charles and Minnie Belle Roux called Take A Chance. The Roux’s diner was a fixture for 38 years, with a menu that included ribs, yellow rice, greens, and macaroni and cheese. Their dessert specialty was sweet potato pie.

One of the few options for black travelers was the “Big House” inn since white hotels were off-limits. A few spare rooms in homes were also typically available, a kind of word-of-mouth precursor to AirBnB.

Henry Simmons ran the general merchandise store, and Willie and Iona Bush operated a dry cleaner (“pressing club”). Many of these stores rented out apartments above or behind them. Nearby, a Masonic Lodge doubled as a community center and early schoolhouse.

Ruby Delaine operated a grocery store. Alfred Wilson and Alfred Simpson each had a barbershop. There was the Francis beauty shop. Lillie Murphy ran a business. You could find an ice cream parlor, pool room, and movie theater. Almost everything you could want… all black-owned!

Many people bought land and platted subdivisions in addition to business ownership. We’ve already talked about Pearl Malloy. Lula Blake purchased a few acres west of 427, where a small residential street bears her name today.

Ida and William Hayman turned fernery work into twenty-two lots along the then brick Sanford-Orlando Highway (427) and Marker Street, near St. John Missionary Baptist church.

Outside the main business district, east of town, Banks Ford owned the popular juke joint Club 436. It was located near the corner of Lake Howell Road (now Anchor Road) and State Road 436. The original was torn down when the highway was widened.

Club 436 version 2.0 was rebuilt just north, owned by Clayton Thomas and Sarah Reese. The duo also owned Club Two Spot in Midway. Home to more than its share of gambling, controversies, and violence, Club 436 was open for over fifty years before it closed in the 2000s.

Billy Lomax started an auto mechanic shop on Highway 436 in the sixties. He was a trusted repairman, beloved by all races for his honest and fair prices. He was known to often be ten times cheaper than other shops. One newspaper article stated that Billy quoted fifty cents for a simple hose repair; the same job that multiple other mechanics quoted $50 or more.

Today, none of the buildings from the black business district exist. Some, like the Ford drug store, were victims of the four-lane expansion of Highway 427. Some were destroyed by fire. Others fell into disrepair, were condemned, and were torn down by the county. No traces remain of this heyday; nature has reclaimed the old business block.

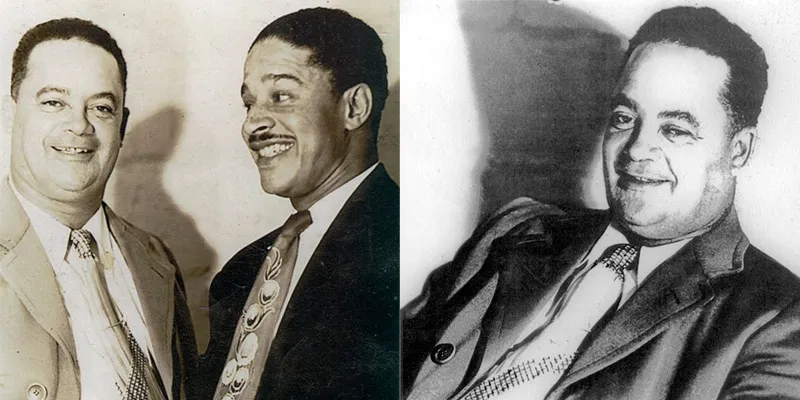

The Famous Condor Merritt

No, I didn’t forget him! Of course, no story about East Altamonte would be complete without the community’s most famous protagonist: Condor Merritt.

His father was John Daniel Merritt, a preacher and farm worker. John came to Longwood before 1885 from Marianna (Florida) with his wife, Maggie Green. She was a white woman whose family shunned her for falling in love with a black man. Her brother, William (or “Buddy”), was effectively adopted into the family, taking the Merritt name and marrying a black woman. Both were welcomed into the community and identified as black in Census records.

Condor had extraordinary ambition and charisma, which he was able to leverage into increasing amounts of wealth. The additional privilege of his light complexion (courtesy of his white mother) allowed him to “pass” as white in certain circumstances.

Merritt started his career as a fruit picker but soon became a straw boss who contracted other laborers to work on his team. He purchased trucks and tractors for his crews.

From there, Condor invested in real estate, including residential property, commercial buildings, and orange groves. His vast business and real estate empire extended through Altamonte Springs, Eatonville, Parramore, Maitland, Forest City, Oviedo, and beyond.

Condor opened a highly regarded nightclub in 1946, Club Eaton. It was in the incorporated black city of Eatonville at the corner of Kennedy Blvd and West Street. It was a swanky joint with a long list of famous performers during the highly segregated times.

The headliners included Duke Ellington, BB King, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Fats Domino, Cab Calloway, The Drifters, Tina Turner, and many more. The performers were popular with people of all races, but their fame did not preclude them from Jim Crow. A major perk of Club Eaton was the bedroom on the second floor, so its stars did not have to hunt for safe lodging elsewhere. This was the “Green Book” era.

For its first few decades, Club Eaton was popular with people of all races around Central Florida. Fans attended its concerts dressed to the nines. However, its importance quickly faded after desegregation. No longer limited to black venues or hotel redlining, the performers began charging many multiples more for concerts. For most of its life, the club was run by William “Billy” Bozeman, who leased the property from Merritt.

Closer to home, Condor owned much of the East Altamonte business district. He owned a beer garden, poolroom, nightclub, cafe, beauty parlor, boarding house, grocery store, and the only theater in South Seminole for black moviegoers. Merritt was the town’s largest landlord, acquiring swaths of land, starting subdivisions, and building houses for rental income throughout East Altamonte.

Lest we polish Merritt’s halo too much, his great success was not without equal part controversy. He spent much of the fifties and sixties as a defendant. Allegations range from being a gambling kingpin, bootlegging liquor, stiffing contractors, and tax fraud. Even within East Altamonte, some called him a slum lord.

That said, none of it can diminish his remarkable rise from poverty and the impact he had on East Altamonte. Condor was a well-known champion for the black community and a proponent of education and political action. His charity of local organizations was revered, and he provided affordable housing, including renting some homes for as little as $7 per week.

As a lasting memorial to his contributions to the community, North Street was renamed Merritt Street in 1993. His daughter, Cora Snead, still lives on Marker Street and was a valuable resource for this article.

Modern Civil Rights Movement

There were virtually no black voters in the post-Ocoee Massacre era of the 1920s and 1930s. Some of that was due to intimidation. Some of it was apathy. But, much of it was Jim Crow laws: arbitrary-enforced literacy tests, poll taxes, white-only primaries, and other policies.

Harry T. Moore, the president of the Florida branch of the NAACP, sought to change that. He lived about 30 miles away in Mims (Brevard County) and founded the Progressive Voter’s League in 1944. With the assistance of local community leaders around the state, the League successfully registered over 100,000 black voters.

World War II played a large role in fueling the dawn of the Civil Rights movement. Blacks fought and died for their country alongside white brothers in arms. They saw much less discrimination abroad. Yet when they returned home, they were once again second-class citizens. That was hard to reconcile, and it demanded change.

Condor Merritt was the most vocal representative of this movement in Seminole County. He had the connections, means, and promotion skills to energize the black electorate, and his influence was widely felt in the county by the 1948 election cycle.

They did not work to promote black candidates. Rather, they wanted to get citizens involved in the political process. Many white candidates saw this opportunity and engrained themselves in the movement. They cozied up to Merritt and others who could swing voters in their direction.

There was a lot of noise around Sheriff Percy A. Mero’s election in 1948, a narrow 229-vote victory over Jack Hickson. While every other precinct in the county was very close, Mero had a 2-to-1 victory in East Altamonte. Merritt was credited for Mero’s win, and many said his influence extended throughout Seminole and Orange counties.

Why did Condor favor Mero? Opponents say it was in exchange for going easy on underground casinos, which were prolific at the time. These charges went to Tallahassee, but the governor cleared Mero of corruption and neglect of duties.

The newly enfranchised black voters were extremely troubling to the good old boy network. They numbered nearly 50% of registered voters in many cities, including Altamonte Springs.

Like the previous movement in the twenties, some candidates (especially Republicans) leaned into it and wooed black voters. But more traditional Southerners (largely Democrats) were not about to show deference to the “inferior race” (yes, this is how many openly referred to blacks and other minorities). Instead, they dusted off the old playbook and used any means necessary — both legal and criminal — to diminish the power of blacks.

Around 1950, the KKK lit a large cross that illuminated the roadway in front of Banks Ford’s drug store — the most visible symbol of the black business district. This was a message, and East Altamonters issued a prompt reply. They extinguished the flames, picked up the cross, placed it down the street in front of a white business, and relit it!

The days of silence and fear were over. So despite continued night rides of white hoods through black communities in Seminole County, they would not be intimidated into backing down this time. But the battle for equal rights was only beginning.

A peaceful Christmas night in 1951 was interrupted by an explosion at the Moore home in Mims. Harry was transported to the closest hospital that would treat blacks, 30 miles away in Sanford, rather than the nearby one in Titusville. He died along the way. His wife, Harriette, died nine days later.

Despite two years of FBI investigation and widely known involvement by members of the KKK, no one was ever indicted. The Moores have been called the first martyrs of the civil rights movement. Sadly, they’d be the first of many over the next two decades.

Although this anecdote is not directly related to East Altamonte, it provides important local context to the backdrop of this period. An educated and active black constituency was feared and resisted by any means necessary.

City Separation

East Altamonte was grossly under-served compared to the white sections of town; that much is beyond debate. It was in near third-world condition.

There were no paved roads and few street lights. The city did not provide garbage collection, and without proper drainage, it was constantly flooding. Most homes lacked electricity. There was no running water; people relied upon cisterns or carrying buckets from the lakes. Outhouses were still common, and even those with septic tanks found them often backed up or overflowing.

Residents were frustrated. They decried “taxation without representation.” Encouraged by a coalition of local pastors and leaders like Merritt, 95% of East Altamonte citizens signed the petition to de-annex its eighty acres. The letter was read at the town council meeting on November 19, 1951. It stated they were taxed “greatly in excess of true value” with virtually no benefits of municipal services.

What was the response from Altamonte Springs’ leadership? No objection. Quite the opposite! The city council admitted to most of the complaints and voted unanimously to do everything they could to speed the process without a lengthy trial.

Sally Faulhaber, chairwoman of the board of alderman, said separation would be better “for both parties.” The mayor, J. C. Goddard, was blunt about his indifference to their conditions. He prioritized making sure blacks could no longer vote in the upcoming city elections.

“I’m not as interested in their rights as I am in whether the white people are elected by a white vote,” the mayor said, “recently candidates for office have done anything to get the Negro vote.”

The circuit court approved the divorce in Titusville two weeks later; the court order came on the eve of the December 5th election for the city council, mayor, and town clerk. This wiped the 205 would-be registered black voters off the rolls, leaving only the 210 white voters.

Mayor Goddard doubled down on his delight over the decision. “I believe the move will greatly add to the harmony in the town in general,” he said, “as there will be no more rivalry and bidding for the colored vote.”

Bolita Brings in Big Bucks

The granddaddy of the Florida Lottery is bolita. The game migrated from Cuba around 1910 and became iconic in Tampa’s Ybor City. Before long, it spread throughout the state.

One hundred wooden or ivory balls are placed in a cloth bag, each with a number from 1 to 100. During the week, players place bets on a number for as little as one penny in the early days. Once a week, the winning number would be selected from the bag and announced. Winning bets paid out between 60–80x the original wager.

At first, the game was largely ignored due to its small bets, but the dollar values grew. Before long, bolita was moving a tremendous amount of cash, and organized crime moved in. The game ran as a massive statewide enterprise. Despite its illegality, busts were infrequent since officials often got a generous cut of the action.

Seminole County was the hub of the Central Florida bolita industry under mob boss Harlan Blackburn. Well… that is… it was under Blackburn after 1953, when the former boss, Ed Milam’s body was found in a swamp near Disney World.

Blackburn’s headquarters was on Red Bug Lake Road. East Altamonte did big business as one of his primary franchisees. Condor Merritt made a small fortune as a Blackburn bolita banker, starting that line of work in the 1940s.

The Merritt Bar served as a local call-in spoke in the gambling ring. Lieutenant duties were handed down to Condor’s nephew Cecil Merritt, who took the bets from around the county. Cecil was named a witness in 1957 charges against Blackburn but (luckily) did not take the stand.

The bolita operations in East Altamonte later shifted to Club 436 under Clayton Thomas, a ringleader from the mid-fifties through the seventies. Thomas’s assistants throughout the county included Sonny Brown, George Solomon, and Sarah Reese. The Thomas-owned Club Two Spot in Midway was another popular place to place and call in bets.

Blackburn’s empire started to erode after he was sentenced to prison in 1973 for dual convictions of tax evasion and the assassination attempt of one of his underbosses (Clyde Lee) in 1971. Thomas filled the void and took over as the bolita king of Seminole County, but it was a dangerous game.

Thomas had two scrapes with death; each time was under mysterious circumstances. In 1956, he was shot at 3 AM on a dirt road near Club 436 after being summoned to meet with a white man parked in a car on the unlit road. Thomas survived but claimed not to know the identity of the shooter. He was again shot in his backyard in 1974.

Increasing crackdowns and momentum toward sports betting as an alternative led to bolita’s popularity falling by the eighties. However, pockets of the game continue in Florida even to this day.

The irony is that despite widespread lottery busts decades prior, the state government entered the business in 1988. It shows that what constitutes a “crime” is subjective, dictated by who makes the money. In many ways, these bolita bosses were pioneers of the Florida Lottery.

School Integration and Losing Rosenwald

The US Supreme Court outlawed segregation in 1954; however, it left the door open for interpretation when it said counties must integrate their schools “with all deliberate speed.” Consequently, the separate-but-equal system did not meaningfully end for decades.

Fast-forward to 1969… “historically white” schools in Altamonte and Casselberry had just a 1–2% black population. Meanwhile, not a single white student was enrolled at Rosenwald. Courts ordered Seminole County to do better in 1970, but due to housing still being (unofficially) segregated, this also mandated bussing to achieve a proportional balance.

In response, the county school board put Rosenwald School on the docket for closure. Their justification was that it only had 14 classrooms, with room for 400 students, compared to the more updated white schools, which had room for 735.

This was a ruse. The board simultaneously expanded existing schools and opened others—like brand-new Sterling Park and Lake Orienta Elementary. And Rosenwald had the area to expand! The real reason was clear: white parents reluctantly accepted that black children would attend their schools, but they refused to send their kids to school in a black neighborhood.

This announcement was devastating to the residents of East Altamonte. Rosenwald represented their roots and their civic dignity. Fighting ensued over where students would be bussed. PTAs fought to accept as few black students as possible; this shipped East Altamonte’s kids on long bus rides like unwanted cargo. It was yet another slap in the face.

As a result, East Altamonte’s parents began a three-week boycott of Rosenwald in February 1975. Nearly 100% of students were kept home. Parents picketed in the streets, accusing the county of stripping them of their “last vestige of a cultural institution.” For three days, black students across Seminole County joined the boycott to show their support, with 85–90% absent from school.

The county school system lost $70,000 as a result of the boycott. Leaders strategically timed the protest to overlap with the period of calculating the student population for funding.

However, the school board did not relent, and a federal court challenge failed. That fall, Rosenwald was closed to traditional students and converted into a school for the mentally challenged. It remained open in that capacity until 2011 and now sits vacant. There has been a recent movement to turn it into a community center.

Changing of the Guard

After the community’s patriarch, Condor Merritt, died in 1972, people began to reassess the condition of East Altamonte. They had disowned the city of Altamonte Springs over twenty years earlier, trusting themselves to Seminole County’s governance. However, the county had invested nothing in upgrading the area; if anything, their neglect was worse.

The roads were unpaved and ill-maintained, and sanitation was non-existent. Without street lights, each night’s darkness fell like a thick blanket. Absentee landlords failed to maintain properties, knowing tenants had no other options. Even into the eighties, 35% of the homes in East Altamonte had no plumbing or electricity. Outhouses and septic tanks often gurgled waste after heavy rainstorms.

Flooding from Lake Prairie’s watershed became a constant threat. In past decades the runoff was manageable except in the worst storms. However, with exploding road construction and development on all sides, nature’s water remediation had been altered, and East Altamonte was its recipient.

The only highlights were generated internally: the civic energy around Rosenwald School, the churches’ prominent role, black entrepreneurship, and its citizens’ generosity. For example, Banks Ford donated the community’s only recreational area (Winwood Park) in 1968.

Contrary to popular belief, the desegregation of schools, housing, and commerce weakened the community. Not only did their beloved school close, but with redlining now outlawed, the town’s best and brightest were suddenly able to leave for more affluent neighborhoods. And most did.

Left behind was a vacuum of power, a feeling of despair, and few options for the poorest of those who remained. Prostitution seeped in from strip clubs a mile away on 17–92. The dark streets became dominated by drug dealers. Its unlit corners and wooded lots made it easy to escape the few sheriff deputies who attempted to crack down.

With those with means leaving town and outside investment in East Altamonte being nill, one must resist judging even those involved in the drug trade too harshly. Desperation has consequences.

The primary customers were white citizens, rolling in with a sports car and depositing cash into the bank of the streets. This effectively served as the only source of outside capital invested in East Altamonte for years.

In the late seventies, the local pastors were the undoubted leaders of East Altamonte. Starting in 1977, the clergy encouraged parishioners to set aside past animosity and rejoin the city of Altamonte Springs.

“Twenty-some years ago black people in this area de-annexed themselves,” said Reverend Carl Brinkley of New Bethel AME. “ They were hopeful they’d get more from the county, but they really got less.”

South Seminole Committee for Progress (SSCP) was founded to lobby for civic-mindedness and government assistance in East Altamonte. James Nelson, its president at the time, felt annexation was the best hope for attracting investment in East Altamonte’s infrastructure, providing activities for children, and improving housing conditions.

“This area needs everything,” Nelson told the Orlando Sentinel. “It don’t have anything. We don’t have nothing up to date. There’s no recreational facilities for children. A lot of dirt streets need to be paved. A lot of streets have been made into dumps. A lot of houses are run down.”

Not everyone believed it was the panacea. Paul Snead, the husband of Cora and son-in-law of Condor Merritt, called it “utopian thinking.” He said, “people have been sold on the idea that the city will solve all of its ills.”

Many old-timers especially resented it, given the past prejudice. But others felt hopeful and opined that the community was a shoo-in for federal grants if reincorporated. The movement eventually gained majority support.

In September 1980, over three dozen attended a city commission meeting and formally proposed re-annexation. 284 property owners of East Altamonte signed the petition. The next step was a ballot referendum that required majority support from both sections of Altamonte.

Publicly, commissioners were supportive of reunification. Privately, though, they doubted it could succeed.

Over 50% of the houses in East Altamonte were considered sub-standard and, if annexed, would have to be brought up to code or condemned. Many could end up homeless.

The other point of contention was sewage, which studies showed was polluting Altamonte’s lakes. Lines had been extended into East Altamonte in the seventies, thanks to federal grant money. However, they mostly went unused since most property owners could not afford or refused to pay the connection fees.

With no clear answers on those issues, the referendum never came. City officials “overlooked” getting it on the 1980 ballot; by 1982, the initiative had run out of steam. East Altamonte would stay independent.

Modern East Altamonte

Today, East Altamonte is in limbo. On the one hand, its situation has improved. Most streets have been paved, and more streetlights have been installed. Most homes have power and plumbing. County drainage investments have improved flooding. Recreational upgrades have been made at Winwood Park and the Boys & Girls Club. Crime rates are way down since their notorious peak in the eighties and nineties.

However, poverty rates are still high, with a median household income of less than $38,000 annually. Many houses are still sub-standard, leaky septic tanks are common, and outside investment has been negligible.

The Pointe at Merritt Street apartments opened in 2017. It was the first outside investment in over 40 years. It created a lot of fanfare, providing quality but affordable housing that is so badly needed. Every unit was sold out even before the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

The Altamonte Springs SunRail station, on East Altamonte’s doorstep, has not yet sparked a development boom around it as it has in Longwood, Maitland, and Lake Mary. But that might be about to change.

A new project is now under construction, extending Amanda Street to the train depot. Its manicured streets with broad sidewalks border beautiful wetlands. It promises to have a drastic impact. Altamonte Springs intends to turn the former swamp into an upscale “new downtown” and an easterly companion district to Crane’s Roost and Uptown Altamonte.

In contrast to anything in its vicinity, East Altamonte has plenty of vacant lots. While many homes have been updated in the last two decades, others are dilapidated homes begging for redevelopment. It’s all prime real estate!

But this is a delicate balance for East Altamonte. The natives — those still there and those who left — want investment in the community, better conditions, and more opportunities. What is not desired, however, is the kind of gentrification that Alycee predicted so many years ago.

So many black communities seen as “blight” by those around them have had their identities erased. Their citizens are forced out by skyrocketing property values, and soon, it’s another indistinguishable suburb without character or historical identity. For now, East Altamonte’s deep-rooted heritage of independence and self-reliance has prevented that.

What will East Altamonte look like in another twenty years? I won’t attempt to predict as Alcyee did. If done right, we’ll see improved quality of life, better infrastructure, attractive residential and commercial development, outside investments, recreational programs, and a growing citizenry.

However, its connection with its proud heritage of self-determination and overcoming hardships should remain unbroken. Integration and diversity are beautiful; homogeneity is not. The aspiration is for a reinvigorated and reimagined East Altamonte, but whose personality and populace survive as unmistakenly African American.

Research

This story has been in the making for five years. I’ve been compiling research since 2017 and am thankful to finally have it completed.

Sincerest thanks to Alton Williams and Cora Snead for their help. Alton has been a good friend and trusted resource. He is working on a book on East Altamonte’s history. So we look forward to his elaboration on this history through countless hours of oral interviews when he publishes it!

Primary Sources:

- Orlando Sentinel Archives at Newspapers.com

- UCF’s RICHES of Central Florida

- Works Progress Administration’s church records (~1940) from Florida State Library and State Archives

- Census and Genealogy Records at Ancestry and Family Search

- Many conversations and texts with Alton Williams, historian and president of Evergreen Cemetery

- Conversation and texts with Cora Snead, daughter of Condor Merritt

- Conversation with Lee Constantine, the former Altamonte Springs city commissioner

- Conversation with Mary Pope

- Sand Pines History in a Shoe Box, by Alton Williams (2019)

- A History of Altamonte Springs Florida, by Jerrell H. Shofner (1995)

- Black America Series: Seminole County, by Altermese Smith Bentley (2000)

- CitrusLAND: Altamonte Springs of Florida, by Richard Lee Cronin (2014)

- Richard Cronin’s blog

- Seminole County Property Appraiser

- Seminole County Aerial Photos

- Justia Court Records

- Court Listener Records

This post is 1173 days old. Comments disabled on archived posts.